Daniel Lee — can lightning strike twice for Burberry’s star designer?

The 37-year-old chief creative officer outlines his ‘democratic’ vision for the British brand ahead of his second catwalk show.

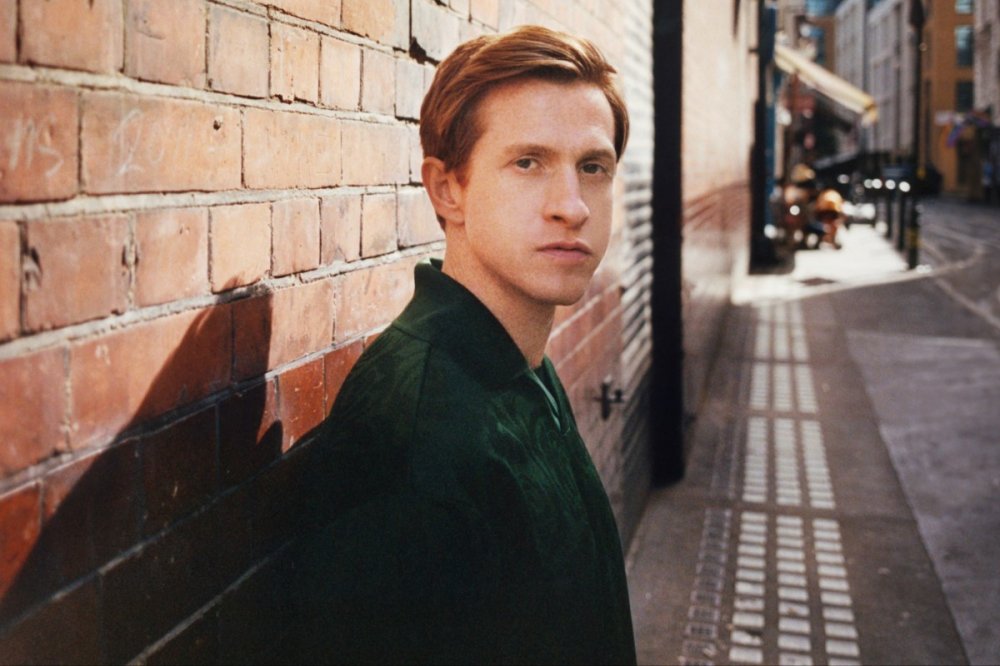

Burberry’s creative director Daniel Lee © Burberry/Tyrone Lebon

Burberry’s creative director Daniel Lee © Burberry/Tyrone Lebon

It is late August in a cobblestoned corner of London’s Soho, where Burberry has temporarily relocated its design studio, and Daniel Lee is clutching a packet of tissues. At another time he might be at home nursing the cold he caught on his way back from holiday in Ibiza, but his second runway show for Burberry is just three weeks away.

Lee is clearly feeling the pressure. Not from Burberry chief executive Jonathan Akeroyd, who in late 2022 hired the 37-year-old as chief creative officer after his abrupt exit from Bottega Veneta, and whom Lee describes as “straightforward” and “sympathetic”, but from himself.

“I feel like the expectations are greater,” Lee says. “The first time around, nobody knew [me]. Coming from zero is sometimes easier than competing with yourself. Certainly I want to do better than I did before.”

It’s a high bar to set. During his three-year run at Bottega Veneta, Lee’s ability to conjure up simple, beautifully finished accessories such as the Pouch bag and woven Lido sandal made him an industry star and reversed the Italian brand’s flagging fortunes. Sales rose from €1.1bn in 2018 to €1.5bn in 2021, continuing to grow even in the worst months of the pandemic, which the company attributed to Lee’s “exceptional creative drive”.

Management is hoping that Lee’s stardust will now land on Burberry, which is aiming to boost sales from £2.8bn to £4bn in the next three to five years. His hire was a coup for a brand that has never quite regained its momentum since chief executive Angela Ahrendts and designer Christopher Bailey led the brand in the mid to late 2000s.

Lee’s first designs for the house landed in stores this week, and they are both more luxe — and significantly more expensive — than what came before. A Rose clutch bag is priced at £1,990, just 15 per cent less than the price of the similarly sized Pouch he designed for his previous employer. A men’s t-shirt printed with the Equestrian Knight from its logo is £620.

Bernstein luxury analyst Luca Solca describes the new price points as “punchy”. “Burberry is trying to price up to look as if it is in the premier league,” he says. “I wouldn’t want this to end like [its former high-end runway line] Prorsum: very high initial prices, very high end-of-season discounts.”

Store buyers are more bullish. London boutique Browns has increased its buy of bags and shoes since Lee’s tenure began. “It’s much more targeted to a younger customer than before,” says buying director Ida Petersson, adding that the quality has improved thanks to changes in its primarily Italian supply chain.

She is particularly excited about the menswear. “The women’s luxury market is saturated,” she says. “But on men’s, everything is up for grabs. Luxury doesn’t concentrate on the men’s side, and it’s really smart [that Burberry is].”

Daniel Lee was raised in Bradford, West Yorkshire, by his father, a mechanic, and his mother, an office worker. He describes himself as an “academic” child who was encouraged to make things.

“I was really drawn to London before I was drawn to fashion,” he recalls, and it was this that inspired him to enrol at London art school Central Saint Martins for his BA. “All of the designers I loved at the time were coming from there — Vivienne Westwood, [John] Galliano, [Alexander] McQueen. London fashion was very theatrical; it was different to what was happening elsewhere.”

He knew of Burberry growing up, but never wore it. “I couldn’t afford it,” he says. “I knew Burberry primarily as an employer.” One of its trench coat factories, still in operation today, is located less than an hour from his hometown.

Lee interned with Martin Margiela and Nicolas Ghesquière at Balenciaga before taking up his first proper job with Donna Karan in New York. He then joined Phoebe Philo at Celine, who promoted him to design director at the brand’s peak. When headhunters came calling shortly after her departure, he agreed to take on the creative director role at Bottega Veneta, replacing Tomas Maier after 17 years.

Lee’s collections for Bottega were an immediate success. Sexy, minimalist and superbly luxurious, they became the closest thing to filling the gap left by Philo’s Celine. So popular (and copied) was the saturated green hue from his spring/summer 2021 collection that it became known as “Bottega Green”. It transformed the brand, long the exemplar of understated luxury, into a bonafide fashion player.

If there was a flaw in the execution, it was that Lee’s Bottega burned too bright, too fast. Over-generous gifting among celebrities and influencers made the brand ubiquitous. On the streets his designs were everywhere, until they suddenly weren’t.

Still, the business grew. And so it was a shock when he and Bottega parted ways in late 2021. A report in trade publication WWD, citing anonymous sources, suggested Lee’s clashes with “pivotal managers” and “veteran artisans” was responsible. Kering, Bottega’s owner, characterised the decision as mutual.

“We ran the course,” Lee says now. “And we took the business as far as it could go in that situation.”

Lee joined a brand in flux. In 2017, former Burberry chief executive Marco Gobbetti, working alongside then-Burberry designer Riccardo Tisci, embarked on a five-year turnaround. The revamp was well received in China, but sales remained flat in the US and Europe, and Gobbetti departed for Ferragamo in 2021, the promised turnaround left unfinished.

Akeroyd, who facilitated the sale of Versace to Capri Holdings for $2.1bn in 2018, has picked up where Gobbetti left off, continuing the development of higher-margin categories such as shoes, handbags and other accessories. They now account for about a third of sales, which Akeroyd has pledged to “broadly double” by 2027.

In one respect at least, Akeroyd’s strategy differs from Gobbetti’s: he wants to reassert Burberry’s Britishness. “It’s unique and helps us stand out in a crowded market,” he told investors last year.

Many observers, myself included, thought that would mean a return to Burberry as it was in Bailey’s heyday: romantic and aspirational, with shows in Hyde Park and trench-coated Cara Delevingne and Malaika Firth splashed on billboards at Heathrow.

But although Lee and Bailey are friendly — the pair were introduced some years ago by Vogue’s Anna Wintour, and the latter appeared at a welcome drinks reception for Lee when he joined and at his first show — Lee’s idea of Britishness is substantially different from Bailey’s. And Britain’s image, post-Brexit and post-Boris Johnson, is not what it was a decade ago.

That was apparent at Lee’s debut show in February, held in south London’s Kennington Park, an area once reputed for its squatters. The collection was casual, outdoorsy and a touch punkish — trench coats were oversized with petrol-coloured faux fur collars; quintessentially English motifs such as roses and ducks were treated with irony; the house’s signature check — a motif Burberry’s designers have treated with caution due to its unsavoury associations with English football “hooligans” in the early 2000s — was worked into fringed kilts layered over leggings with a grunge feel. These were paired with wellie boots and a grainy leather Knight bag with carabiner-style hardware in the shape of a horse’s head — the kind of bag, Lee said backstage afterwards, meant to be chucked on the floor.

Many of the looks were splashed with the house’s recently reinstated Equestrian Knight in a bright blue, a colour the brand is no doubt hoping will come to be known as “Burberry blue”.

A resort collection released via lookbook the following June was more refined. Seeing it in person for the first time at the studio, I am struck by its textural quality and the thoughtfulness of small design details such as subtle “Bs” worked into the buckles of attractively weighty equestrian-style boots, and a Prince of Wales check coat given a psychedelic flourish above the hem.

Lee himself is wearing a pair of burgundy-check trousers from the first collection, with raised ridges that mimic the gabardine weave used in Burberry’s trench coats. “I like to go hard into the detail and perfect every inch of what I work on,” he says, rubbing the fabric between his fingers. “It drives me mad; it probably drives the team mad.”

Before he started, Lee says he “did a lot of thinking about what Burberry should be. For me it’s this idea of building a more democratic brand.” He also wants to “celebrate the idea of ‘Made in UK’, which unfortunately hasn’t been looked after and preserved as it has been in other countries.” To that end, Burberry recently collaborated on a small run of hand-made men’s shoes with Tricker’s of Northampton.

He says that one of the challenges of working with UK suppliers is scale. “The reality with Burberry is that it’s huge. At another brand you might be selling 50 of a coat, but here we’re selling 5,000.”

Partnering with local artisans is a tried-and-tested component of a brand elevation strategy. But at a time when luxury brands are jostling to become ever more exclusive and premium, and VICs (very important customers) are more critical to the bottom line than ever — not to mention Burberry’s own recent jump in price points — will “democratic” sell?

“It is about the whole,” Lee replies. “We can have elevated luxury and build quality in accessories. But at the same time I don’t want to alienate the football fans, the younger generation — I want to celebrate that part of Burberry too. And I think that’s what’s very unique about the mission here. Often luxury is just pushing upwards, upwards, upwards — and I also think we still cater to our younger clients as well.”

I am struck by his determination to succeed, and to sell — he is not a designer who shies away from the commercial demands of the job. He may not yet have an “it” product on his hands, but I have little doubt he is the right designer for Burberry.

Browns’s Petersson believes Lee “learnt some lessons” from his time at Bottega Veneta. “There’s a strong and steady long-term plan here, which is better than fast hits.”

Lee has a reputation for working late into the night and through weekends. Do he and his teams work that way at Burberry? “We ultimately have to get the job done,” he says after a pause. “There’s a lot to do.”