-

Watch Live! The 2025 VS Fashion Show.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Haider Ackermann - Designer, Creative Director of Canada Goose & Tom Ford

- Thread starter MissMagAddict

- Start date

anothermag.comCollections Digest | Haider Ackermann on Masculinity

— July 23, 2013 —

Unique documentation of men's and women's fashion collections

“I wanted to challenge myself”, said Haider Ackermann when asked what made him finally decide to create his first-ever menswear collection (bar a one-off show he did at Pitti in 2010). There was a certain poetic reflection on the limits of masculinity in the contrast between the tough-looking, heavily-inked models and the fit-for-a-dandy tailored duchesse satins, embroidered silks and fringed scarves. But while none of the pieces would look out of place in a woman’s wardrobe, the collection was unmistakably virile and clearly designed for a man who doesn’t need to prove himself. After the show, AnOther talked menswear and masculinity with the designer.

How is the working process different when designing menswear, as opposed to womenswear?

There is more of a sartorial spirit to menswear. For womenswear, the search for beauty and elegance in an abstract way may be more of a drive, but designing for men is a fully down-to-earth job. You can’t “drape” a man, so instead you concentrate on the garment, making the sleeves just a little shorter or the trousers just a little tighter, all the while searching for a certain style, a certain attitude.

Almost every model cast for the show was tattooed. How did that relate to your masculinity ideal?

I was very inspired by models like Jimmy Q or Daniel Bamdad: their beauty is extremely masculine but also kind of romantic. The poetry of having their life story written on their bodies really touched me and made me think that, after all, their rebellion is their sophistication. I really wanted to pair their unique styles with the nobility of my clothes.

The collection, with its extreme luxury, was a reflection on dandyism. What defines a 21st century dandy?

Today’s dandy has evolved. He does not, as Baudelaire would say, “live and die before a mirror”. He doesn’t exist by defiance and for a world of empty appearances; instead, he takes pride in the liberty and the singularity of his words, gestures and excesses, which is never easy in a world where everyone is constantly judged. He is brave.

Text by Marta Represa

Marta Represa is a freelance writer specialising in fashion, art, photography and culture.

ultramarine

chaos reigns

- Joined

- Jan 7, 2003

- Messages

- 6,421

- Reaction score

- 56

Right now he is in Colombia. He got invited to show at Colombia Moda. A friend of mine met him and will interview him.

wwd.comM: Haider Ackermann in Plain Sight

By Matthew Schneier

Haider Ackermann cuts an uncommon swath through the world of French fashion. He has the dark, whiskered, romantically dramatic look of a nineteenth-century gaucho, though he is—by birth—from Colombia, half a continent north of the pampas. By upbringing, he is nearly unclassifiable. He was adopted by a French cartographer and his wife and raised in Africa and the Netherlands; later, he was educated in Belgium and trained in France, between which he now splits his time. In the middle of August, when all of Paris is having its holiday in the South of Italy or the South of France, he is not hard to pick out at a table at the Café Marly, overlooking the Louvre, in his crushed fedora and shawl. But it is still easier to mistake him than to place him. “When I was young, I used to go to bars in New York, and when people would ask me what I was doing, I would say I was cleaning dishes in a bar,” he said, with half a chuckle, not long after we’d met. “And due to my skin color, they believed me.” This of a designer who instructs the members of his small studio in at least four languages: English, French, German, and Dutch.

The fact is, the past few years have made it much harder for him to hide. Once the perennial periphery man, he has come very near to the center of the fashion whirl, a move confirmed by the placing of fashion’s most potent of laurels: envy. Everyone seems to want Ackermann, and there is hardly a major fashion label whose helm fate, or the rumor mill, has not inclined him toward. His name was bandied about for positions at Margiela (which he acknowledges) and Dior and Givenchy (which he does not); and a few years ago, Karl Lagerfeld, the creative director for life of Chanel, named him the only designer working who would be fit to replace him someday.

Ackermann forged his reputation on the strength of his women’s collections. They are made of elaborately draped, wrapped, and ribbon-tied acres of silk and jacquard, seeming to draw on every global tradition of dress, from the Indian sari to the Japanese kimono to the Middle Eastern chador. The least debt, in fact, is to the best-known, Western tradition. Although he freely acknowledges the influence of the mid-century couturiers Madame Grès and Yves Saint Laurent, fabric seems to matter more to him than fashion. “It was not fashion I was touched by,” he explained of his earliest interest. “It was the movement of the fabrics. I lived in countries where they used six or eight meters of fabric. My mother can tell you: When I was a child on the beach, I would always hang my towel to see the wind blowing through it.”

Even today, he lives not in the cosmopolitan center of Paris, but farther afield, in the twentieth arrondissement. “Saturday morning, I wake up at nine o’clock and read the newspapers,” he said. “Africans walk around, Asian, Jewish, all different nationalities. They have the weirdest combination of clothes. You have all those people talking to each other. It’s nothing pretentious. There’s so much fashion on the street, but not fashion, which for me is very inspiring. It brings me back to when I was younger, living in Africa.”

Because draping is central to the way he designs for women—and, as he once put it, “You can’t drape a man”—Haider Ackermann never designed menswear and never much thought about it. Until, in 2010, the Florentine trade fair Pitti Immagine invited him to present a women’s collection and underwrote the cost of doing so. They gave him, Ackermann recalled with some relish, carte blanche. He decided on the Palazzo Corsini for his location and began to envision the woman he’d dress there. “I always make up stories to myself—that’s how I always work,” he said. “She’s wandering through the corridors to her room, and of course she’s lonely. Of course she’s waiting for the man. He’s going to come home, but she doesn’t know when. I saw her walking, I saw the whole thing. But who’s the man that she’s waiting for, actually? What does he look like?”

The show opened with Scott Barnhill—once a waifish star of nineties male modeling, now appealingly weather-beaten—in a sash, smoking slippers, and a jacket so finely embroidered, he looked like the famous Phillips portrait of Lord Byron. And suddenly Haider Ackermann was a menswear designer.

....

wwd.comThe reactions to Ackermann's first foray into men’s were good. Though his hosts reacted initially with some trepidation—“We were surprised, and even a bit worried at first, about it overlapping with the men’s guest,” Pitti CEO Raffaello Napoleone said recently—they agreed to the coed presentation, despite having invited Raf Simons to show his menswear collection for Jil Sander, because the project was “really a special, creative experiment.” Ackermann himself saw it this way. The collection was not intended for production or sale. “It was just an exercise for me,” he said, “and a very liberating one, because I felt totally free. We didn’t need to sell. It was such fun.”

But retailers, their appetites duly whetted, wanted it in stores, and so it was ushered into production. In a major show of support, Barneys New York picked it up. “Haider Ackermann uses fabric the way that most people use color,” said Barneys’ Tom Kalenderian. “I think there’s no question that it’s a very personal and unique presentation of men’s.”

Personal is a word that comes up often when Ackermann is concerned. Further than that, journalists writing about his collections tend to stumble and fall back on calling them, simply, “very Haider Ackermann,” which becomes a kind of shorthand for draping, exotica, and rich color. He works closely with a small team and refuses to employ a stylist, working instead with Michèle Montagne, a legend in Paris fashion who collaborated with Helmut Lang during his glory days and shepherded the careers of Rick Owens and Ann Demeulemeester. Technically, Montagne is Ackermann’s press agent. “That’s almost the least she does in my life,” he said. “I could do without her press, but I could not do without her in my collection. Michèle, she knows what I’m going through. She knows that my collection is so built on my emotion, whether I’m sad or I’m in love. All of this translates somehow. When we’re working on the looks, she can take more out of me than I dare to do. A stylist would never come so personally, because he wouldn’t know my life. He’d just come in and change the things.”

Ackermann has long nurtured relationships with muses who become avatars of his vision—most famously, the actress Tilda Swinton, but also the high-fashion models who return, like family, to his runways season after season—but where menswear is concerned, Ackermann’s best representative might be himself. He has an aristocratic bearing and a dab hand with a cashmere wrap. (Over the course of lunch at Café Marly, he readjusted his blanket-size square of fabric several times: now as an oversize ascot, now tucked under the arm like a toga.) “You can see his work, and you can see what he wears, and you can see the ties, you can see the bridge,” said his close friend, the jewelry designer Waris Ahluwalia. “You can see that story being told. You don’t even need to read between the lines.” Ackermann conceded that connection; his friends, he said, point out the Ackermann spirit in his menswear in particular. “They recognize me in it, but I don’t know—I don’t have that much distance yet to be able to analyze that,” he admitted. “Perhaps I don’t even want to. Perhaps I just want to let it go. That’s more the freedom I have with the man—I don’t think that much. With the woman, I am more thinking, rethinking, overthinking.”

But there is an umbilical tie between the collections for men and the collections for women, one not lost on any of the Ackermann faithful. “Truly, it feels like part of the same story,” Swinton said. “The delicacy of color palette, the clarity of line, the fluidity of some silhouettes and the sharpness of others.... Personally, I find it occasionally hard to remember which collection something came from.”

As abruptly as Ackermann's menswear appeared, it disappeared again. Despite the sales orders, the season at Pitti was followed by several seasons of silence on the menswear front. “Shops were requesting more, but I'm not a person who responds to ‘You have to do it, you have to do it,’” he said. “Pffffft. When I feel ready, when I feel it’s the moment.”

“I think this collection was missed as he exited men’s,” Kalenderian said. “People were asking for what’s next. The anticipation was always there, that it would come back. It was just a question of when. So I think, unfortunately, none of us knew except him, so it was a hard question to answer.”

The moment turned out, as Ackermann moments often do, to be a personal one. “I chose some fabrics for the women, and I thought, Oh, that fabric. I would love to have for myself,” he laughed.

“So let’s do men’s now.”

....

wwd.comIn June, a hundred people were invited to Ackermann’s rapprochement with menswear. It was a late addition to the Paris calendar that brought out every major editor and retailer. What they arrived at was not a baroque runway show of Pitti-esque proportions but a nearly silent presentation. In a raw space in the Marais, sixteen models, tattooed up to the neck and down to the knuckle, sipped champagne and chatted among themselves. They wore silk jacquard waistcoats and iridescent bomber jackets, long scarves and shimmering overcoats, all in saturated jewel tones: garnet and aubergine, lilac and midnight blue. If they posed, it was mostly incidentally. They were more like guests of honor at a cocktail party the underdressed rest of us had crashed. Ackermann was delighted. He’d won over the harder audience. For a designer whose native mode is self-doubt—Ackermann is famously sensitive—menswear seemed to provide a way to release the pressure valve. “I said something to my press agent which she had never heard from me before,” he said. “She said, ‘How do you feel?’ I said, ‘Actually, I’m good. I loved the reaction from the boys, because they loved it. If the press doesn’t like it....’ ”

The press, for the record, did. Several key editors raced back to place personal orders, Ackermann reported, by way of sales prognostication, and retailers followed. (Barneys has picked up the collection again for spring, Kalenderian confirmed.) And now the collection will continue without interruption. The ongoing menswear line will be part of Ackermann’s new, independent company. Less than a month before the show, the Belgian angel investor Anne Chapelle, who, under the aegis of her company BVBA 32, had supported Ackermann for years, announced that in order to facilitate further growth, the label was splitting off into its own separate entity. (Ann Demeulemeester, whose label was also under the BVBA 32 umbrella, became an independent firm at the same time. Chapelle continues to hold a controlling interest in both brands.)

The possibilities for growth are many. To the continued, dogging questions of taking over a luxury house, Ackermann will now say only that the fit must be right. “You don’t have a sensitivity that can filter everything,” he shrugged—the implication being that his filter might be of finer stuff than the feed. In any case, while he once flirted openly with the idea of taking over a house with a vocabulary distinct from his own, the feeling now seems to be that it’s Haider’s way or the highway.

He maintains an auteur’s single-minded dedication to his own idiom. “I don’t have this talent that Nicolas [Ghesquière] or Ms. Miuccia Prada has to renew every season,” he said. “I wish I had it, perhaps.” The “ultimate dream,” he went on, would be to have a haute couture line. But in the meantime, maybe a film, maybe a ballet. “I almost worked on a film with Jim Jarmusch,” he tosses out with a casualness that seems genuine, not practiced. “We met, and he knew so much what he wanted that it was almost useless for me to collaborate.” The highway.

It's not that Ackermann’s focus is rigidly self-reflective or that he designs only for himself. It would be a poor business strategy for a luxury fashion line to do so. But his work comes from somewhere not far beneath his thin skin. A recent trip to his native Colombia, as an invited guest of the Colombiamoda trade fair, seems to have piqued his interest in memoir even more. (It evidently confirmed his Latin roots as well. “It was really nice to see him there amidst his people, on his land,” said Ahluwalia, who was among the delegation that visited Medellín with Ackermann. “We would go out dancing every night, and he’s a great dancer. Look—you think those are French moves? It’s so obvious. You think that’s his French side? That’s Colombia written all over it.”)

“His work is always profoundly personal and explicitly grown out of his experiences,” added Swinton. “Maybe his recent discovery of Colombia has liberated him to put out there all his interests, well-rounded and transparently free of limitation.”

It’s not autobiography, exactly. If it were, Ackermann would be as extensively illustrated as the tattooed models he loves. “It is a challenge I would’ve loved to do,” he said wistfully. “It was Tim Blanks who put it quite right—perhaps I want to be one of them.” Many of his designs, he said, he couldn’t, or wouldn't, personally wear.

But the personal is the professional, and the professional the personal. And as his own story wends its way on, so does his collection, in all its ups and downs. Lunch was over, and Ackermann was headed from the Louvre back to his studio in the Marais, alone. I offered to accompany him, and he politely but firmly demurred. No one was allowed to observe him in the studio. It was too personal. Instead, he offered this crumb. A few seasons ago, he said, he gathered his studio staff and told them the story he wanted to tell for the season.

“‘So you have to imagine it’s five o’clock in the morning, you just stayed in this beautiful hotel with the person you love,’” it began.

“‘But suddenly you need to go. And you walk in the mist. You know that you’re losing the person you love, but you know that you have to do it, because otherwise you’re losing yourself. So you have to go to the mist and see it. Stand straight and face it and deal with it, that you have to go....’ I explain the whole thing. Four of them started crying. Because they knew. I didn’t tell them that I had just separated, but they knew it wasn’t the woman who just left the hotel, it was me leaving the hotel at five o’clock in the morning. And I found myself in the mist, in Paris, not looking back, thinking, I let this person go. I don’t want to, but I have to, because otherwise I lose myself. They gasp. And afterwards, they’re like, ‘Do you want a tea?’ They would never [before] touch me, but they hug me. Then I say, ‘I’m fine. Let’s work now.’”

fashion1001

Member

- Joined

- Dec 2, 2005

- Messages

- 107

- Reaction score

- 0

Haider Ackermann is so amazing! I have always been fascinated with him as a designer and person. His designs never fail to captivate me season after season. Great thread!

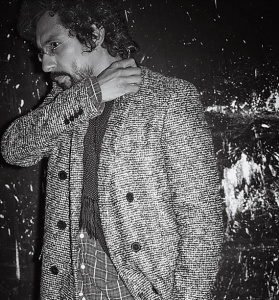

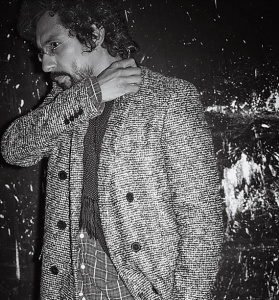

Ph: Ezra Petronio

wsj.comIT IS NOON ON SUNDAY in early January, and Haider Ackermann alternates between sipping coffee and Perrier in the library of the understated Pavillon de la Reine hotel in Place des Vosges—one of his favorite haunts in Paris, where he puts up his parents when they visit. The designer's studio, around the corner from the hotel, is more of a creative pied-à-terre think tank than his Antwerp headquarters. "In Paris, I'm on my own with my assistant," he says. "We talk about what I want to do and start drawing. Here is the cocoon. Then we go to Antwerp, and I translate my work to the team and make it real." He spends half the week in France and the other half in Belgium.

Ackermann is 42, with thick, curly black hair pomaded back, and tiny wire spectacles just covering his eyes. He wears a loose, blue plaid shirt and a silk polka-dotted scarf jauntily knotted around his neck. The look is rounded out with purple socks, pointy black shoes and drop-crotch gray trousers with green side-stripes (the pants are his own design). On one thumbnail is a smattering of chipped teal polish; the other is black. The outfit may sound extreme—grunge–meets–pirate–meets–marching band drummer—but he pulls it off. In fact, this free-for-all hopscotch through aesthetics is the foundation of his fashion, a mini empire that is expanding with last year's introduction of menswear.

Although the once-underground it-designer has evolved into a major fashion player—his clothes have become red-carpet staples of cerebral fashion-forward stars like Tilda Swinton —will he continue his slow-burn momentum to become a full-scale multi-category international brand?

"I don't think I'm searching for success," he says. He's had no problem stumbling into it, but he admits there's more at stake this go-round. "I'm more nervous," he says of his sophomore men's collection, which he'd show the following week. "The first time there was a sense of freedom—you just do it. Now we have shops, it needs to sell. It's more concrete."

Ackermann made a brief foray into men's clothes in 2010, by presenting looks (as a special guest women's designer) at Pitti Uomo, a trade show in Florence. It was a barrage of dizzying prints and silky pajama-like pants. "They gave me a budget, and I could do whatever I wanted," he says. "I wondered, Who is the man behind the Ackermann woman? And then I let it go because I was not ready."

A full collection didn't appear until spring 2014. Now in stores, it blends vagabond Byronesque romance with Rebel Without a Cause swagger and gypsy wanderlust. The palette includes fuchsia and mauve, and he doesn't skimp on silk. It was an across-the-board critical hit, even with American men's magazines that often shy away from more outré European designers. It also impressed retail fashion directors. It is being sold in 20 countries, including Barneys and Saks in the U.S. "He's an artist like a painter or a sculptor," says Tom Kalendarian, the executive vice president for menswear at Barneys. "He will only do what he wants to and loves."

The collection isn't the most practical, but that's not, nor ever is, Ackermann's point. His flair for dressing women has translated to men is even more out there. "His menswear takes bohemian dressing to another level," Kalendarian says. "You don't necessarily identify his clothes with a brand as much as with the person who wears them—a man who looks unique and artistic. There is a mood of romanticism—sometimes his pieces look like a dressing gown or a smoking jacket. They conjure an image of someone sensual and mysterious."

The photographer and artist Katerina Jebb, a friend, has been documenting Ackermann's shows since the beginning. "Haider has a good relationship with his inner world," Jebb says. "It's a motive for what he makes. He allows himself to leave rationality. It's not 'what do we need: trousers, a sweater and a pair of sneakers?' He goes beyond necessity, which is what true luxury is. Who needs a silk peignoir? You don't need anything made of silk or velvet, but you dream about it. He's cultivating people's dreams."

ACKERMANN'S fashion-without-borders approach corresponds to his globe-trotting upbringing. Born in Colombia, he was adopted by French parents as an infant. "My sister and brother are Asian," he says. "We had to fight to make people believe we were a family." His neighborhood in Paris, Ménilmontant in the 20th arrondissement, is similarly multiethnic.

His father was a cartographer, and the family lived in Africa during Ackermann's childhood—Ethiopia, Chad and Algeria. "I have beautiful memories," he says. "But of course it was an unstable life. Even today, if I'm too much in one place I want to move and go on the road again." His wanderings affect his work subliminally. "Even in India," he says, "I never take pictures. I absorb things and try to remember them. If they stay in my mind, then it's meant to be."

In Africa, he studied ballet and dreamed of becoming a dancer. When he was 11, his family relocated to a small Dutch town, where his passion for dance waned. "In Africa, we were dancing in a T-shirt and bare feet," he says. "I went to Holland, and there were all of these girls with blonde hair and tutus. I didn't speak the language and was the only dark-skinned person and the only boy."

He learned Dutch (he also speaks French, German and English) but felt like an outsider. "I was silent," he says. "I wasn't the person I wanted to be. We lived in a bourgeois area. I tried to be like the others and wasn't myself. It was difficult to come to school in Holland with my skin color. I was always dreaming of escape."

As his interest in fashion developed, he saw that it was a means for both assimilating and for standing out. At 17, he moved to Amsterdam on his own. "I was still shy," he says. "I discovered nightlife and everything around it. I'd go to the wildest party without drinking or drugs, just observing."

At 22, he enrolled in fashion school at Antwerp's Royal Academy of Fine Arts. "I was not the most disciplined student," he admits. "In Africa, we were free, and there was wildness about it. In Holland and Antwerp, you had to follow what the teacher said. This was strange. I only wanted to go to school if I had something to say. If we had to do 10 silhouettes, I would do five." He was asked to leave without graduating.

"Suddenly all your dreams are not coming true," he says. "I thought I'd never make it. How can an insecure introvert make a career after being kicked out of school?" Ackermann stayed in Antwerp and worked at various discotheques. "It didn't mean I wasn't drawing every day," he says of the period. "I was dreaming, fantasizing, wishing and hoping. Every day I was thinking about my work." He credits his tight-knit circle of friends with pushing him to make his debut collection.

"I had a huge lack of confidence," he says. "My friends pushed me into throwing myself into the troubled waters. My mother told me the only thing you can lose is money, but you will regret never trying." He funded this venture himself with savings from working in clubs.

With his debut show in Paris, in 2002, he became an indie outsider on the fashion calendar. One could use words like fluid, liquid and undulating to describe Ackermann's abstract and lyrical oeuvre. "My work is built on emotions," he says. "It's complicated to talk about it. I find it difficult myself." His debut was picked up by Barneys and Colette. It also begot a lucrative gig designing for leather house Ruffo.

In 2005, his label was acquired by the Belgian investment group BVBA 32, whose chief executive is Anne Chapelle (their other fashion holding was Ann Demeulemeester ). "I'm an investor of not only money but of my time and energy," says Chapelle. "Haider has a personality I believed in." Even so, she thought the company desperately needed infrastructure. "I started with point zero with Haider. Together, we built it stone by stone."

The merger allowed Ackermann to follow his muse. "It gave me a sense of freedom," he says. "Before, I was packing boxes by myself. Now I could concentrate on my work." In June 2013, the fashion label separated from BVBA 32 to become an independent company, Atelier Haider Ackermann (Chapelle is the CEO). The women's line is now sold in 35 countries at more than 180 outlets.

....

wsj.comWHEN WE MEET, Ackermann has just returned from Los Angeles. "I was escaping," he says. "It was the first time I really spent time there. I was in Laurel Canyon for six days in a house in the hills with a garden."

Upon his return, he began preparing the fall men's presentation. None of the models at the pre-casting fit the bill. It made him long for California. "You see these characters—men walking around with their own style," he says of his West Coast trip. "I was so inspired. Then I came to Paris and just saw beautiful boys. I was lost. The clothes have to live to tell a story. If you just do beautiful clothes on beautiful boys it fades away." Ackermann seeks something for the eye to latch onto, a resonating fault. "I like the failure in a man," he says. "You need a distance, something unreachable and broken."

Ackermann's fall 2014 men's presentation was in a chilly vacant Marais space on January 15—a sober collection of tweed, herringbone and gray flannel—but in his hands the result was hardly staid. The overcoats were long and sumptuous, more akin to a king's cloak than a mac. Some baggy silk and cotton jacquard pants featured an intricate print of abstract geometrics suitable for a mosque wall. Like all Ackermann shows, it was difficult to describe—mystic, swashbuckling businessmen explorers?

Taking such traditional materials and transforming them could be seen as subversive, with great crossover appeal, but those terms are too crass in describing Ackermann. "The decadence and extravagance of last time came from all the silks," he says. "This time, I wanted it to come from the inside. It was more subtle. I was thinking of Detroit and Chicago in the '40s. There is also something very deadly about it."

Akin to his personal style, there were scarves galore, of which he has a philosophy. "I don't feel naked with one," he says. "It sounds weird, but I feel more protected."

The next day, Ackermann will catch an early train for the weekly two-hour journey to Antwerp. "I like to read all the gossip magazines," he says. "I love trash. People are surprised that I can be light. They think I'm this heavy person. There is a dark cloud in there, but at midnight I will be dancing on a table. That's my Colombian side, and there is no tomorrow."

IndigoHomme

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Mar 20, 2014

- Messages

- 2,964

- Reaction score

- 1,520

PARIS, France — Berluti, LVMH's lossmaking luxury shoe maker, is in talks to hire Paris-based designer Haider Ackermann to replace Alessandro Sartori who returned to previous employer Ermenegildo Zegna in February, two sources close to the matter told Reuters.

Ackermann, a respected figure in the fashion industry known for his super-imposed layers, draping and dark style, will be expected to give Berluti a sharper, more modern fashion edge.

"The talks are ongoing, therefore the timing of an announcement is not clear yet," one of the sources said.

Ackermann created his eponymous brand in 2003, which is only distributed through wholesalers and online retailers.

LVMH declined to comment, as did a spokeswoman for Haider Ackermann.

Created in 1895 and specialising in €1,500 ($1,667) luxury shoes with a peculiar two-tone shine and finish, Berluti has been trying to re-invent itself as an upmarket ready-to-wear brand.

Analysts estimate Berluti burned €100-150 million since LVMH stepped up investments five years ago and LVMH boss and controlling shareholder Bernard Arnault placed his son Antoine at its helm.

Back in 2011, LVMH had grand ambitions for Berluti which it aimed to use it as a platform to gain more exposure to what was then a vigorous luxury menswear market, driven by strong Chinese demand.

In the past two years, however, the luxury sector has slowed sharply and Chinese men's appetite for luxury shoes and clothes has become much more subdued.

Berluti opened flagships in every major city and invested in its website. Today, it has more than 50 stand-alone stores and is estimated to incur around €50 million of losses on a turnover of around €150 million ($166.68 million).

Back in 2013, Bernard Arnault said he expected Berluti to become profitable in 2016.

Berluti is regarded by the financial community as one of LVMH's problem children together with Marc Jacobs but for different reasons. Last year, LVMH announced it would discontinue the Marc by Marc Jacobs line which was more affordable than the Marc Jacobs line and the restructuring dug holes in the company's accounts.

LVMH said this week it did not plan to sell the loss-making Marc Jacobs company after agreeing to sell Donna Karan International, the parent of New York label DKNY, to US clothing firm G-III Apparel Group for $650 million.

LVMH said Berluti's losses had narrowed in the first half but it did not say when it expected it to become profitable.

vía BoF → https://www.businessoffashion.com/a...uti-to-hire-designer-haider-ackermann-sources

YohjiAddict

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- May 26, 2016

- Messages

- 3,655

- Reaction score

- 5,179

LVMH trying to pull off a "Pheobe X Céline 2.0" building hype around a brand on the verge of non-existence. However...

a) It's not 2011 and LVMH should know better than to hire Haider, whose hype is nowhere to be seen in 2016.

b) Pheobe was already quite a star back in her Chloé days with a substantial fan base and an expertise in selling over-priced leather products.

I would like him to be succesful but I predict no such luck. Time will tell.

a) It's not 2011 and LVMH should know better than to hire Haider, whose hype is nowhere to be seen in 2016.

b) Pheobe was already quite a star back in her Chloé days with a substantial fan base and an expertise in selling over-priced leather products.

I would like him to be succesful but I predict no such luck. Time will tell.

RedSmokeRise

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- May 31, 2015

- Messages

- 1,743

- Reaction score

- 1,145

As a shameless fan, I am 100% here for this.

Lola701

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Oct 27, 2014

- Messages

- 13,685

- Reaction score

- 36,135

I love Haider and he is doing certainly the most sensual menswear at his own brand but i don't believe in this.

I hope it will work for him but i don't expect it to be that successful.

Another great candidate for Hermes who is taken by LVMH.

I hope it will work for him but i don't expect it to be that successful.

Another great candidate for Hermes who is taken by LVMH.

Similar Threads

- Replies

- 46

- Views

- 9K

- Replies

- 205

- Views

- 41K

- Replies

- 10

- Views

- 4K

- Replies

- 1K

- Views

- 131K

- Replies

- 980

- Views

- 139K

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)

New Posts

-

-

Versace Eyewear F/W 2025.26 : Joseph Quinn & Aimee Lou Wood by Blommers & Schumm (13 Viewers)

- Latest: upNorth

-

-

-

...

...