Alaïa’s Pieter Mulier Is Following a Legend—And Pushing the Storied House Into the Future

BY NATHAN HELLER

September 28, 2023

In the moments before the start of Alaïa’s ready-to-wear show in Paris this past summer, the house’s creative director since 2021, Pieter Mulier, stood out among the team for his qualities of ease and calm. He spent some minutes chatting with his backstage visitors. He wandered over to the makeup room, found he wasn’t needed, and sat on a curb with the model Julia Nobis to smoke Marlboro Golds and talk. Shows weren’t always so comfortable—his last one, held within his own apartment, in Antwerp, had driven him into a nervous state—but this one took its rhythm from the summer evening and announced Mulier’s advancement to a master’s station. The runway would be the Passerelle Léopold-Sédar-Senghor, spanning the Seine between the Tuileries and the Musée d’Orsay. This bridge was one of the city’s quiet marvels of engineering, and, as the sun aligned with a western breeze, it exemplified the warm and precise refinement that has given Mulier’s work at Alaïa its magnetic appeal. “I try to keep a little bit of the family aspect of Alaïa in the studio,” Mulier says. “Everything is on a human scale.”.

At 44, Mulier is at once a new arrival in the firmament of creative directors—Alaïa is the first house he has led—and one of fashion’s ensconced steady hands. For 16 years he served as Raf Simons’s deputy and sounding board, moving along with his mentor’s career as it rose toward ever-larger labels and distinguishing himself not only by his creative point of view but by his skill in managing large teams. When he was picked to succeed the Tunisian-born designer Azzedine Alaïa, who died in 2017 after reimagining the language of body-conscious tailoring, many wondered whether Mulier could finesse the transition, teasing forth the brand’s fragile magic while pushing his own fresher vision through. “Alaïa felt so specific to Azzedine and to that time that it seemed it was going to be impossible for it to happen again,” says Julianne Moore, who found herself rejoining the collection waiting lists after Mulier’s debut in the summer of 2021. “Pieter managed to do it.”

In person, Mulier is tall and skinny, with a boyish whoosh of hair just graying and a teenager’s spidery way of dangling his forearms from cocked elbows. He dresses most days in white or black sweatshirts and jeans (no logos) and leads his house in the spirit of a team captain, calling plays from the field and cheering colleagues on. At a fitting two days earlier, he kept the show music cranked up and struck prattling conversations with the models as they entered. “When you’re waiting for your fitting, all you hear is ‘Wow!’ and clapping,” says the model Élise Crombez, who grew up half an hour from Mulier. “It was as if every girl was specifically chosen for her outfit—you felt like a person, not just a number walking down the runway.”

Mulier himself wears the same white atelier coat as his staffers backstage, an egalitarian gesture that matches his straightforward manner: He is Flemish, and can seem as buoyant and pellucid as a glass of summer ale. His approach to the craft, though, is rarely so simple. Even beyond his workday, Mulier haunts galleries and artists’ studios, compiles scrapbooks and archives, and picks apart garments like old radios to understand the way they work. Where some designers operate as inward-turned iconoclasts, he sees his fashion as one offering in the long, shared practice of forming a point of view about ambitious art. “I still think fashion should propose something, say something—because it’s part of culture,” Mulier says.

The theme of the bridge show, inspired by Mulier’s fascination with the clock of the Musée d’Orsay, is time. (To start a collection, he likes to say, he needs only a shoe and a venue.) He saw reclaiming time as urgent in an increasingly ’grammed-and-forgotten fashion world. Unlike most houses, Alaïa still shows only twice a year; in the ’90s, Mulier observes, Azzedine was known to cancel shows at the last minute if he deemed the work unready. If taking time was Alaïa’s superpower, Mulier thought, why not celebrate that on the runway?

When he thought about clocks, he envisioned buttons. “I quite like the idea that you need time to get dressed—and you need time to get undressed,” he says. If the moment of doing up buttons was one of self-making, empowerment, their undoing measured out erotic time. This focus on the physicality of clothing and the body was itself very Alaïa, Mulier thought. His invitation package to the show had been unconventional—a three-legged folding chair that guests were told to bring with them. Now the grandees of the fashion world are arrayed along the bridge in their makeshift seating, which seems a statement about transience and environmental use, but also an impish gesture of democratization. “I love the idea of the fashion crowd walking with a camping chair through the most bourgeois area of Paris,” Mulier says.

“Raf Simons came up after the exam to offer Mulier his card. “He said, ‘I don’t think you’re an architect; I think you’re a fashion designer’ ”

A breeze comes up; the garments dance. There are autumn coats and hoods and hats paired with sheer vinyl skirts and dresses. There are translucent plissé pieces in black and beautifully tailored white. There are haunting yellowy pinks and blues and earth tones, blouses with high collars and sharp cutouts, corsets, leggings, trousers cut in the Alaïa silhouette, wrapped boots, leather suspenders, and an exquisite amber-colored vinyl overcoat. Alaïa makes a point of melding ready-to-wear and couture into a single retail collection, and its garments are famous for their unusual construction: They are designed not on pattern tables and mannequins but directly on the human body, built like houses from the inside out with proprietary dynamic-tailoring techniques. Many wearers suggest they’d know the feel of an Alaïa dress with their eyes closed. “They hug you,” Crombez explains. “It grabs you,” Mulier agrees. “They don’t just hang. In French we say tenu—you’re held together.”

He takes this also as a mission statement for the house, which employs a tight, close-fitted four-person design team and four small specialty ateliers—tailoring, draping, knitwear, and leather.

At last Crombez appears, against a stirring ostinato in low clarinets by the composer Gustave Rudman, to close the show. The choice is one of intimacy: She and Mulier are nearly the same age and grew up speaking the same Flemish dialect. She’s dressed in an exquisite black high-neck translucent dress with a band of low, lean ruffles at the hips, black heels with an A-shaped cutout at the toe, and a belt of polished gold. Passersby on the Quai Voltaire have gathered to watch, hanging entranced over the river’s high embankment. The fashion show has bled into an easy Sunday evening in Paris, building up a spectacle not just for the fashion observers on their chairs but for the Parisians and the tourists who pause—who take the time—to watch before, just like the models, heading on their way.

A couple of days later, Mulier is back in Antwerp, where he’s lived, with interruptions, for two decades, feeling upbeat. “It’s fantastic!” he exclaims as he heads to lunch. “This guy put his restaurant in the ugliest surroundings.”

The restaurant, Veranda, faces a concrete train overpass. The founder is his friend the chef Davy Schellemans, whom Mulier has repeatedly enlisted to cook for Alaïa’s most honored guests. Mulier loves amazing things nested just slightly off the beaten path, greatness that doesn’t advertise itself but attracts a devout community of people who bother to take the time to look. A waiter—Mulier knows the staff by name—brings tiny mugs of cool broth flavored with summer tomato, handmade cauliflower ravioli served with pink and gray Belgian shrimp, and morsels of local chicken dressed with chickpea cream and fermented honey sauce.

In Mulier’s view, he explains while devouring his chicken, Alaïa’s golden age was the period extending from the ’80s to the ’90s—the period when Azzedine created a new language that both revealed and mystified a woman’s curves. Azzedine blended light, classically feminine materials with tougher ones, like leather. There was knitwear tailored like a jacket, at once tidy, professional, and sensual: a revelation at the time, and one of the most lasting profiles of the ’80s. “Azzedine was a tailor,” Mulier says, the key, he thinks, to the work’s blend of femininity and strength. “He brought ease to sex appeal—which is unbelievable.” This sex was never compromising;

it was French.

By the end of Azzedine’s life, Mulier thinks, the nectar had soured. “Alaïa became a little bit the vestiaire of the bourgeoisie,” he says. “I remember going to art fairs and every gallerist was dressed in Alaïa—the same dress with the same shoe. It’s never good if you become the synonym of ‘good taste.’ ” The brand had lost the young and restless. “Kids didn’t know what Alaïa was,” Mulier says. “The mother was wearing it; the daughter was not.”

“Alaïa felt so specific to Azzedine that it seemed impossible for it to happen again,” says Julianne Moore. “Pieter managed to do it”

It became clear to Mulier that his mandate was to wave away the brand’s accrued perfume of stodgy money and correctness and get back the young, daring spirit that had made Azzedine a revolutionary and sensation. Seeing the house’s strengths, he began to try to isolate and correct for its tics. Shoulders and arms were cut much too tightly for the contemporary woman, he thought; he brought them out. Jackets had a way of ending up more sculptural than comfortable, so he opened up and modernized their lines. He added product categories at lower price points—swimwear, eyewear, underwear—to welcome younger consumers. And he tried to bring the sexy back.

After pecking at a strawberry sorbet—“Fan-tastic!”—Mulier heads outside to light a cigarette, then climbs into the back of a black minivan that ferries him around. (He recently acquired a 1978 Porsche 911, but the van life gives him opportunities to work through his perpetually overflowing WhatsApp queue: Everybody seems to have his number.) Mulier usually comes to Paris for the workweek and returns to Antwerp for the weekend, by train or by car. Whenever the van was on hire for an Alaïa job, the driver placed a huge ashtray in the back seat.

On his way home, Mulier stops off at the extensively renovated Royal Museum of Fine Arts to marvel, as he sometimes does, at Flemish painting.

“My favorite one is that one,” he says, pausing before Rubens’s triptych Epitaph of Nicolaas Rockox and His Wife Adriana Perez. Why? “It’s small,” he says. “I quite like Rubens when it’s small.”

Not far away is a gallery filled with the vivid, dreamlike expressionist canvases of James Ensor. “He’s one of my favorite painters,” Mulier offers, slowing before The Skeleton Painter, which shows a deathly skeleton behaving as an artist. He adds, offhandedly, “He was actually born where I am from.”

Mulier grew up in Ostend, a seaside resort town in west Belgium that he describes as “surreal.” “They always say that people in Ostend are very creative—and a bit crazy,” he says. His extended family was from Bruges; his father was a doctor, and Ostend, with its wealth of health spas and casinos, needed personnel. Mulier has an older brother and a sister, and describes himself as a “very social, very easy” child, albeit one without broad skills. “My brother was a big football player, tennis player, rugby player—every ball he got in his hand,” Mulier says. “My father was frustrated that I didn’t have that.”

Instead, he gravitated toward crafts, drawing, piano lessons, drama class. He revered his mother’s father, a shirtmaker on commission to the Belgian monarchy, who managed three hundred seamstresses. “I always thought that he was an artist more than a businessman,” Mulier says. “He spoke seven languages. He lived in modernist houses.” To the young Mulier, this urbane shirtmaker seemed the height of worldliness, a figure steeped in art and bigger dreams. “What I learned from him was that you can do whatever you want in life,” he says. Yet it never occurred to him to follow his grandfather into the garment trade.

At 11, Mulier went off to the Abdijschool van Zevenkerken, a Benedictine institution outside Bruges—his uncle was a Catholic bishop—that he describes as being “like Harry Potter.” Boarding there during the week, he learned Latin and Greek and the basics of art appreciation; he made friends with whom he remains close. Mulier describes himself, during these years, as “very classic”: a happy, straight-edged provincial Northern European schoolboy with a happy, straight-edged future. He was in the Boy Scouts until the age of 19, at which point, at the suggestion of his parents, he went to law college in Leuven, rooming with boarding school chums who’d done the same.

Yet the study of law failed to excite him, while architecture did (he liked the minimalists: Álvaro Siza, Peter Zumthor, Toyo Ito, Rem Koolhaas), so after two years he switched to architecture school, at the Institut Saint-Luc, in Brussels. It proved a revelation. Brussels was the largest city in which Mulier had ever lived, and the edgier creative people he met there thrilled him.

“It was the beginning of my world becoming bigger,” he says. Mulier’s urbane girlfriend at the time, at pains to broaden his taste, led him through a world of art. “She took me to every gallery, all the museums, and fashion stores.” The only living designer Mulier had ever heard of then was Dries Van Noten, but his girlfriend had pictures of the newest Raf Simons collections on her walls.

They were students together. One design course required a final project on the theme of “survival.” Simons had agreed to sit on the exam jury. “You had a lot of the people in school making, I don’t know, jewelry rings so that if they got attacked in the street they could knock a person down, stuff like that,” Simons recalls. Mulier interpreted the prompt quite differently and showed up wearing a bodysuit that would supposedly ensure survival of any job interview: Strapped into a one-piece garment, with no shirts to come untucked or flies to come undone, the idea went, a job candidate was freed from unwitting self-sabotage. Simons did a double take. “It was a completely different way of thinking,” he says.

As Mulier remembers it, Simons came up after the exam to offer Mulier his card. “He said, ‘I don’t think you’re an architect; I think you’re a fashion designer,’ ” Mulier recalls. “I said, ‘No, I don’t think so.’ He said, ‘I think you are.’ ” Simons proposed that Mulier visit his atelier in Antwerp—an invitation that Mulier recalls answering with polite indifference. “Then my girlfriend said, ‘Oh, yes, you’re going,’ ” he explains. Three months later, knowing almost nothing about fashion, Mulier showed up in Antwerp to begin the internship that changed his life.

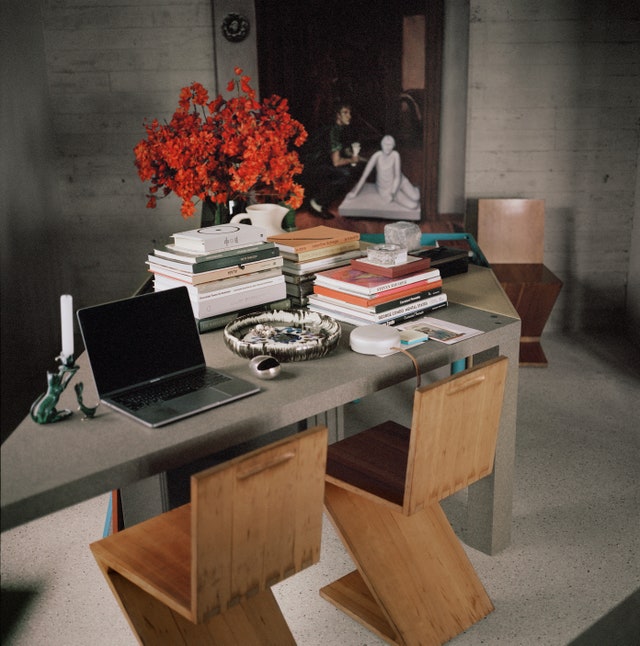

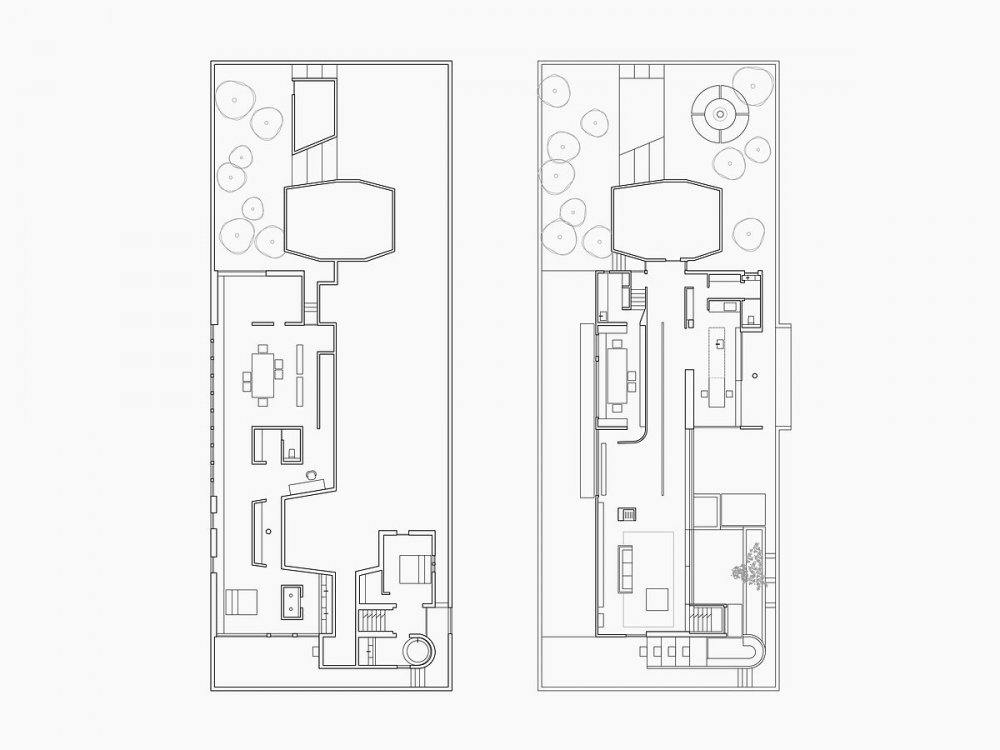

The city of Antwerp is at once human-scaled and expansive, encompassing the second-largest harbor in Europe. Its old center extends from squares of gorgeous Flemish town houses; its more recently rebuilt regions have an industrial air, traced with green. In 2014, Mulier bought the penthouse of the Riverside Tower, a concrete modernist icon designed by Léon Stynen and Paul De Meyer and completed in 1972, on the city’s “left bank”—a parky residential flatland that Le Corbusier once tried to lay out as an ideal neighborhood. Mulier spent two years renovating the apartment, which had been De Meyer’s own home, with the help of the architect Glenn Sestig and the landscaper Martin Wirtz, who designed him a distinctive rooftop garden based on ivy, irises, grasses, and trees. And he filled it with new art: Tim Breuer, Bendt Eyckermans, Steven Shearer, and much more. (“I think I prefer artists to fashion people: There’s something more direct in what they do,” he says.) A favorite word of Mulier’s is extreme, and the penthouse, which looks out both on downtown Antwerp and on the waterfront, is proudly that. Every species of plant in the garden, Mulier says, was chosen because it had survived the explosion at Hiroshima. When he held an Alaïa show here, on a chilly day last January, models paraded through his library, his office, and his bedroom.

“It’s like an island, because we’re so high,” Mulier says, glancing now in satisfaction at the river and the city spread below. “It’s a little world outside the world.”

When Mulier is in residence, he wakes at a quarter to seven—his windows, which are huge and trapezoidal, have no blinds—makes himself breakfast, and returns to wake his dog, John John, who sleeps with him in bed. They walk together for an hour in the nearby woods. At home, he showers and starts sending emails. If it’s a workday, he’s at it from 9 a.m. to somewhere between 7 and 9 at night; then he and John John walk again, and he meets friends for dinner, or cooks—one of his favorite things. By 11 or 12, he’s back in bed. “It is actually quite classic, my day,” he says, as if the thought were just occurring to him. (In Mulier-ese, what’s “classic” is what’s not extreme.) Zoom was, for him, the best thing to come from the pandemic: He has not set foot in New York since 2019, when he and Simons and his former partner of 16 years, the designer Matthieu Blazy, all living there, left Calvin Klein. “I was so happy in New York,” he says. “It would break my heart to go back.”

On free weekends, he tools around the apartment and the galleries, goes to the gym, cooks for friends at home, and, on Sundays, visits his brother and his sister and their families around Ostend. (“I love kids,” he says. “I always wanted kids, because it brings balance to a life—reality when you are in an industry like this. But I would never do it alone.”) He adores Antwerp, but has always, he says, experienced it from a slight social distance: a lesson he feels he learned from Simons, who taught him to approach the city through its artistic underground over his first year at the label—a period when Mulier learned basic skills like patternmaking and contract management and felt, he maintains, “completely lost creatively.”

“I’d gone from a law school to an architect school to—a company in Antwerp that dresses skinny boys? The first show I saw from Raf, I was like, What is this? My father saw a picture and said, ‘That’s what you do?’ ”

And yet, at Simons’s label, Mulier underwent a kind of bloom. He lived for a year in the office, sleeping on a mattress underneath the archive. Simons brought on Blazy, another young designer, and in time, as Mulier came to acknowledge his sexuality, the two of them started to date. They found joy in being part of a scrappy team of kids who spent hours in the studio, living inside art and design and, from a quiet Belgian city, making work that enthralled the entire fashion world.

“Raf used to bring us all to the Frieze art fair, to Art Basel, and have us look at things that, honestly, I’d never seen before, and explain why they were important,” he recalls. “I believe that everybody in life has one person who does that for you: a professor in school, or a parent, or an uncle. But I didn’t have that at home or in school. I had it when I met Raf—that person who pushes you so far out of your comfort zone that it changes everything.” By the time Simons commuted to Milan to work at Jil Sander, Mulier, who did the brand’s shoes and accessories, was known as his right hand.

“It was a very interesting combination,” says Blazy, who is now creative director at Bottega Veneta, “because Raf would think in terms of concept, where Pieter would think immediately as an architect: in volumes, colors, product.” When designing, Mulier drew in profile—“You could see the volume of the clothes,” says Blazy, who internalized this sidelong method—and created his shoes bottom-up, as if designing a building.

All the while, Mulier dreamed of designing womenswear. When he realized, deep into his 30s, that the closest he had gotten was making women’s shoes, he had a kind of crisis and decided to launch his own womenswear line. It was 2010 and, as he was ramping up the collection, his father became terminally ill. Mulier paused the work. “I took care of him for six, seven months until he passed away,” he says. By then, Simons was moving to Dior and invited Mulier to join—this time, he’d work on womenswear, including couture, an offer he could not bear to refuse. “I knew after a week at Dior,” Mulier recalls, “that this is what I wanted to do.”

It was at Dior that Mulier’s quiet genius for color, volume, and construction—the material personality of a garment—came to the fore. “He was interested and challenged by the technicality,” Simons says. Dior—like Alaïa—was a tailoring-based house, and it was where Mulier learned the power of a recognizable silhouette: the box (Chanel), the hourglass (Dior), the long hourglass he would one day master at Alaïa.

As Mulier tells it, though, Dior was most of all where he learned how to sell a dream. “It was about curves,” he says. “It was about attitude.” The lesson lodged in his imagination even as, in 2016, he and Blazy joined Simons in New York to lead design at Calvin Klein—a résumé bump for Mulier, who was listed (and paid) as the brand’s creative director, and a crucial window into the inner workings of both global commerce and, he notes in earnest, underwear. The Antwerp trio was alive with an ambitious dream: They were going to take sublime, smart, daring, first-rate fashion and make it globally available. But for Mulier, the experience had the radiance of a candle burning at both ends, filled with almost nonstop travel among Europe, the US, and Asia.

“You’d arrive in Amsterdam in the morning and have 50 people in front of you with 24 hours to work with them—and you’d have to give them energy,” he explains. “You’d clean it up, leave, and come back every three weeks to do it again.” By the time the project ended, “I was just burned up.”

For a year, he turned down job offers that came his way. Getting restless during the pandemic, he considered becoming creative director of a Swiss furniture company. “I thought, Oh, furniture, it’s so calm!” It was at this point that Alaïa came into view.

“I had this idea that Pieter should go to Alaïa,” Clémande Burgevin Blachman, who had known Mulier at Raf Simons and Calvin Klein, recalls. Her mother had been a close friend of Azzedine; she thought she saw, in Mulier, a designer who could bring the house to life again with the old energy. “I knew he had this way of looking at the feminine body—maybe it’s because of his background as an architect—and this cultural and art knowledge,” she says. “I convinced him he should find a way to apply.”

The application process lasted a full year. “We were dating,” Mulier says wryly. “I told them, I’m not going to cheat on you—I’m going to wait.” What he recognized in Alaïa, long before a lot of other people did, was a house that joined the intimacy and particularity of Raf Simons, the refined ateliers and dream-making of Dior, and the demotic openness of Calvin Klein. He became convinced it was the lead job he was made for. Over 12 months, he ordered vintage Alaïa garments and studied their construction as an architect might study French cathedrals, learning Azzedine’s language in cloth.

When Mulier and Blazy were together in Antwerp, they often ended their days at De Zeester, a family-filled tavern-style restaurant a moment’s walk from the apartment. Tonight Mulier takes a round table and orders gray-shrimp croquettes, mussels, and a bolleke, or goblet bowl, of local beer. He knows the server by name here as well. “My dog is obsessed with her,” he says.

Since he and Blazy broke up, they’ve split custody of John John, who travels back and forth among Paris, Milan, and Antwerp, sleeping in the back seat of the car along the route. When he’s away, Mulier misses him acutely. “My day is based on him,” he says. “He’s at Alaïa constantly: He’s in the ateliers. He’s downstairs. He’s in the studio. An animal brings something calm to the teams.” John John lives with him more than Blazy, and he frets about the fairness of that, but he finds himself counting the days until the dog’s return. “I went to Milan just to see him,” Mulier says. “We’re on that level now.”.

Mulier and Blazy had the fortune and the misfortune of each seeing their luckiest breaks—a once-in-a-lifetime chance to lead, at last, the world-class fashion house that each believed in—appear at almost exactly the same time. For years, they had been partners in deputy-ship, the two base corners of a triangle. Then, overnight, each had become the sovereign of his own imaginative world.

The weight of two such new mantles, based in two cities, with two chief calendars and desperate drives to squeeze the most from a rare opportunity, was more than one relationship could bear. “Once you obtain that job, you have to make some choices in your life, because it eats a lot of everything around you,” Mulier says. He chose Alaïa, Blazy chose Bottega Veneta, and the rest was sealed. Today, the two of them are still among the most enthusiastic fans at each other’s shows. “What I like about Pieter’s way of working is that he goes against the stream, takes risks, but he’s not someone who wants to shock—he’s just going for what he believes in most,” Blazy says. But they remain apart. “It didn’t work anymore, based only on that—only on the jobs,” Mulier says.

A loss, though, has been balanced by wild success. At Alaïa, the vision that Mulier most believes in has the public heart. His first collection alone turned the fortunes of the house around. A set of hoods that he updated from an early Alaïa model worn by Grace Jones sold and sold and sold—a fashion icon right out of the gate. “It represents Alaïa in a very simple way, and every big house copied it,” Mulier notes. “It’s one of those pieces that made other brands look at Alaïa again.”

They are still looking and, more than two years later, the hoods continue to sell dazzlingly well. Success is generally worth waiting for, at least in Mulier’s view. “We’re a small company. It takes a lot of time,” he says. He smiles, then shrugs: After two decades of biding his own time for the right big break, he was used to taking opportunities in pace. Now he had all the past to work with, and the future. “I’m very patient,” Mulier explains.

), add the suits into the equation, have them plug Hedi's 2005 broken record into Phoebe's void: the babydoll looks, the groupies, the women who are cutesy and adorably emaciated whose most exciting period of their lives are from ages 16 to 20 and revolve around following men in bands and.. you have the violent reaction and what you perceived as slutshaming.