Haider Ackermann takes the Tom Ford Throne

As he prepares to lead the world's most seductive brand, the acclaimed designer has never felt more free

By Murray Clark

Photography by Sølve Sundsbø

21 November 2024

In the 19th century, leading American spiritualists were into the idea of Summerland: an afterlife that was a personalised heaven of sorts. It could be a little house on the prairie; a rococo mansion; one long glade filled with butterflies and lambs and other nice things. But a Haussmannian atelier two storeys above Paris’s Place de Madeleine feels pretty close to a universal paradise. Cloud-white walls reach up high, buffered from the ceiling by a fine cornice horizon. Three huge mirrors surround an angular wooden bench. There’s a distant tinkling of a piano’s ivories from somewhere. It’s almost comically tranquil (or comically French, I can’t decide). And in this sanctuary sits the designer Haider Ackermann. He likes it here too.

“I love living in Paris,” he says, rolling his eyes and grinning. “For God’s sake, I am French. In Paris you can disappear; I don’t have that sense in other cities. You always meet people, bump into people. But here? That doesn’t happen at all.” He looks out of the window, pausing for a moment to admire the crisp September sunlight like a very happy cat. “I love to bike around early in the morning at 6am and discover new streets and new angles and new corners. It’s amazing.”

Paris, with its hellish traffic, doesn’t seem like the most obvious place of monastic peace. But for someone like Ackermann, to go incognito is a gift. The fashion designer has a name that commands almost universal respect in an industry prone to mob mentality – grab your digital pitchforks, brothers, a creative director has choked. Not so with Ackermann. Everyone seems to like him. Even the mean ones in the fashion press corps like him. But more importantly, everyone is excited by him – now more than ever. After taking the reins of Canada Goose in May, he’s just been officially appointed the successor to the Tom Ford throne. “I’ve been… working,” Ackermann says, not-so-fresh from a New-York-to-Paris red eye. Still, despite the lack of sleep, his face cracks into a wry, barely there smile. He cuts a warm figure that belies a Google Image search, which nets a collection of serious greyscale portraits. He is blessed with cherubic black curls and impressive angles. He smiles a lot. He leans in conspiratorially. Ackermann moves my espresso towards me, an open palm silently gesturing for me to enjoy: “Yes, quite busy lately.”

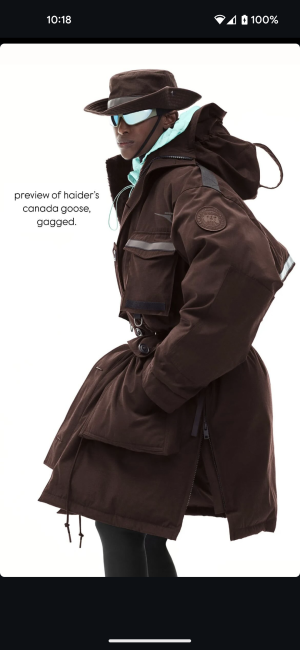

The Tom Ford announcement generated the same amount of noise as a major Premier League signing – and the same level of media fervour. “A perfect match for a sexy brand?” asked The New York Times. “He will knock the ball out of the park, this is an appointment you can feel excited about,” wrote one user on fashion-nerd subreddit r/whatthefrockk. Over on YouTube, style pundit Fashion Roadman quickly dropped a video titled “Will Haider Ackermann Transform Tom Ford’s Legacy?” It’s a huge engagement, and a move to such a deep-pocketed company requires one to do the rounds with the stakeholders, the shareholders and the holdovers. (Estée Lauder acquired Tom Ford for £2.15 billion in 2022.) That is a job in itself. But Ackermann has always been busy building and nurturing his own plot in fashion’s landscape. His patch is colourful, fertile and regal. His work – for Berluti, on red carpets, at a watershed 2010 Florence menswear debut – manages to dazzle without ever tiptoeing into the gauche. And while that translates well to deeply exquisite runway shows, it has worked at Canada Goose, too. For an out-and-out outdoors brand, Ackermann’s turn was always going to riff on some idea of gorpcore. That’s a tough gig when so many critics prophesied the trend’s doom. But where a slew of outdoor-tech brands oscillate between apocalypse chic and “aw, shucks” comfort, Ackermann’s version is closer to a utopian elegance. The temperature of the future may be at freezing, but his sculptural, billowing parkas could settle the Arctic in pops of emerald green, rose pink and electric blue. The expeditionary hats are sharp, almost aerodynamic, and skew closer to Stetsons. In Ackermann’s winter palace, all is well – and acutely tasteful. “It’s not a question of reinvention. I don’t think that’s the purpose I have. It’s just to put a little bit of electricity in there,” he says. “The Canada Goose archives have the most fluorescent colours: pink, orange, yellow, all back in the days of 1957. Now you can go into the shop, and it’s muted colours – navy blue, black – so I try to embrace that older part.”

He’s been drawn to vibrancy since his childhood, which was pretty unconventional. “I grew up in Africa. Ethiopia, Chad and Nigeria,” says Ackermann, the Colombian-born adopted son of an Alsatian cartographer. “Then we moved to Holland when I was 12. A few years there, then Belgium.” It was here he began his formal fashion education at Antwerp’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts – a place that felt like the polar opposite to his worldly youth. “I didn’t feel at home there. Due to my past, I always kind of felt like a stranger. Sometimes there’s a comfort to being a stranger. You’re the observer,” he says. “But in Antwerp, I didn’t feel like the good stranger. I came from countries that were so bright and colourful. But here, the sky was so low, it felt like you could almost reach out and touch it.” Despite this, and an expulsion from art school for failing to turn in coursework, his tutelage was also a hard-won lesson in how he could improve his fashion standing, and his understanding of it. “It was not a circus,” he says. “In Antwerp, there’s so much respect for the person who wears the clothes. You carry the clothes more than a lot of other countries. There’s a beauty to that.”

This masterful tightrope walk between fantasy and function has been perfected over the better part of three decades. His signature is sci-fi, but sumptuous; sexual, but subtle. The resulting Haider Ackermann own-label stans are many. They take it seriously, too. Johann, a model in Stuttgart, is quite proud of a funnel-necked sweatshirt in a very Haider shade of Martian desert: “I was going through this vintage store in the city called Vintendo Archive. The simplicity [of the sweatshirt] stood out really. Even though you can wear it as a statement piece, you can also just wear it as a normal basic.” Francis Kassatly, a TikTok fashion pundit who encourages people to “buy less, buy better, wear it more”, is into Ackermann’s “heavy use of noble fibres like silk and cashmere”. He’s followed the designer for years, too: “I was in my 20s, so I had to buy intentionally. The first item I ever purchased was a gold velvet bomber with ruched sleeves. It was a size too large but I grew into it over time. It’s eight years old now, but wearing it still feels as fresh as day one.”

Ackermann feels like a serious fan himself – especially of the auteurs of fashion who seem to float above the marketing-product churn. “Luxury needs to be defined,” he says, when asked about the industry’s current state. “Oh my God, so many luxury houses don’t feel luxury for me. They don’t make me dream like they used to. We only talk about sales and figures but we have a responsibility to the next generation. I remember so many designers that made me dream, whether it was Mr Saint Laurent, or Helmut Lang, Rei Kawakubo; all of them.” I ask if all the dreamers have been lost to this insomniac world of profit margins and bottom lines. “All is never lost,” he says. “Look at the work of Rick Owens, or [Nicolas] Ghesquière, or Comme des Garçons. I look up to them all.”

Many members of fashion’s cognoscenti have spoken highly of Ackermann in the past. “Well, hopefully not all in the past,” he laughs. I mention Karl Lagerfeld, the late designer who felt more like Chanel’s tinselled emperor than its mere creative director. Ackermann nods respectfully. In 2010, Lagerfeld seemed to publicly anoint Ackermann as his heir apparent, telling Numéro magazine: “I have a contract for life, so it all depends on who I would like to hand it to. At the moment I’d say Haider Ackermann.” That must have been a head-f*ck of the highest order, I say. “It was very strange, because he and I were obviously quite close. But we never spoke about it,” says Ackermann. “I think his purpose was more to put the light on me – ‘Look at this guy.’ I’m not sure he really would have liked me to be at Chanel.” There’s a pause in the room, Ackermann tilting his head. “Y’know, he would always send me flowers just two minutes before a show. Two minutes before, I would get flowers. I always took it as a gift, and… it was a beautiful push.”

Ackermann also caught the attention of Jean Paul Gaultier, the grand couturier who made sailors sexy and pop-cultural history out of conical bras. In January 2023, Ackermann debuted his collection as guest creative director for the brand, a custodian role that has carouselled through head designers ever since Gaultier retired in 2020. Menswear press rarely attend haute couture shows (these are the most artistic and meticulous collections, made exclusively for top-tier clients, a large proportion of whom are women with offshore bank accounts). So I didn’t get to see Ackermann’s colossal symmetry of feathers and beading in person – but Dazed fashion features director Emma Davidson did. She was, in her own words, “gagged”. “I think Haider’s Jean Paul Gaultier collection was the biggest surprise for me, and maybe even up there in my top few as the collaborations I’ve loved the most,” she says. “When that men’s coat that was crafted from thousands of pins came down the catwalk, you could genuinely hear people gasp – because the soundtrack was so low, you could hear them bouncing against one another, and it became this whole -sensory thing. I think he’s one of the sexiest designers out there right now.”

Ackermann surveilled Gaultier himself for the duration of the show. His reaction was the most important. And, unsurprisingly, he was won over. “Attending the Haider show and watching all the stunning looks on the runway, I found myself feeling like a client,” Gaultier says. “I was thinking, I would absolutely buy this.”

“To work on haute couture was the reason why I did fashion in the first place. [I wanted] to collaborate with all of those people in the ateliers. It is a complete love affair,” says Ackermann.“I don’t know anyone who is more passionate than all of those women who sit for hours and hours destroying their eyes, because they have to be so focused. Everything counts for them.”

Ackermann’s pursuit of beauty has taken him across the fashion landscape. In October 2023, he launched a collab with cult rich-lady cosmetic brand Augustinus Bader. In 2024, it was a crossover with Fila that nodded to the luxury raver (that collection, in its kaleidoscopic opulence, isn’t so far from his work at Canada Goose). Before that, he was creative director at Berluti for three seasons, a period he describes as “a beautiful journey”. Under Ackermann, the storied leather goods house took a turn to the streamlined with clean, razor-sharp separates that felt sexier and quietly self-assured. By 2018 standards, before big houses routinely burned through creative directors, his three-season reign was relatively short. But still, it’s a period that the designer looks back on fondly.

In this age of “overnight success” artifice, Ackermann’s rise is more honestly chronicled. After leaving Antwerp, he interned for the arch enfant terrible of ’90s fashion, John Galliano, who made a huge impression. “He was so convinced by the story he would tell every different person, every model,” Ackermann says. “You’d believe in his dreams, you would enter his dreams. And that’s a gift – to convince people about beauty.” In 2001, Ackermann put this worldbuilding masterclass to practice. His womenswear debut in Paris was the first collection under his own name, and it immediately played his trump card: a sophisticated futurism full of draping. For decades he has managed to create squeaky-clean angularity with draped fabrics that feel tailored and form-fitting. Many designers would achieve such simplicity by shearing fabrics and stitching them together; Ackermann layers them like a master atelier of ancient Rome.

It’s right there as he sits opposite me, wearing an off-white Prada sweatshirt over his shoulders. But rather than knotting at the sternum, Ackermann’s is tied artfully at the upper collarbone. The Italian cotton rolls across his chest like a Viennetta ice cream. (I have tried to recreate it many times in a mirror with my own sweatshirts to no avail, for these hands are not Haider Ackermann’s.)

This sort of expertise attracted investors to his label, and Belgian entrepreneur Anne Chapelle became a major backer and owner of the brand in 2013. But as the fashion industry was paralysed by the Covid pandemic, Ackermann all but left the company amid reportedly significant losses. Chapelle retained the brand name in a licensing agreement, and there was a rumoured legal fallout as Haider Ackermann, the fashion house, ceased production in 2020. “When I got my name back, it was a relief,” says Ackermann. “My name is everything I own. It’s the name that came from my parents, and as an adopted person, it’s the only thing I have from them. So I treasure it. Knowing that someone could take it away from me…” He pauses for a moment. “I’m not interested in talking about that period of my life.”

And yet still, there was another lesson to be taken from this episode. “Before, I was very naive. If kids asked me for advice, I’d say, ‘Follow your dreams. Don’t let anyone stop your dreams.’ But nowadays, you have to be anchored in reality and surround yourself with lawyers from the first minute. It would have changed my life if I’d have done that,” he says. “Creative people are in a bubble. We’re thinking about fabrics and the little colours and we don’t think any further.”

The creative process hasn’t been all love and light, either. I point to a 2017 Q&A with online interview directory The Talks in which Ackermann spoke at length about his own dark places. “I mean yes, I wasn’t happy. I was not breathing,” he says. “I knew something was wrong, and I knew I was in this bad situation and everyone told me so. And sometimes, out of fear, you don’t step out.” He rattles through concerns that you assume might plague a fashion creative at his level – concerns one rarely hears out loud. “You might not work any longer. You might not have any shows any more. And that’s what my world is about, what my work is about. I allowed it because I was scared to lose all of this. And now, I can breathe again.”

Tom Ford often feels like a label steered not by the heart, but by the loins. Ever since the designer broke out at Gucci in 1995, sex has fuelled his grand machine. Not bawdy, primal, guttural sex. But flashy, desirable, an otherworldly sort of sex that’s more gilded than it is p*rn*gr*ph*c; think of Nicolas Winding Refn, the director of Drive and The Neon Demon, if he were to produce an erotic thriller set in Studio 54. For Tom Ford, it is a sex that’s detached from reality, and one that smartly utilises the power of suggestion; a Gucci campaign from 1997 shows a metallic heel pressing into the skin of a man’s bare, carven chest. That one simple image can launch a thousand mental images more complex and graphic in nature (granted, other campaigns were a lot more explicit). Thus, Tom Ford built an erotic empire of elegance and sensuality, with a tiny bit of disco thrown in for fun.

As one of few eponymous fashion labels to become an actual household name in the 21st century, Tom Ford holds jurisdiction over menswear, womenswear, beauty, fragrance and leather goods to the tune of millions. As former Vogue critic Tim Blanks wrote in his review of a spring 2014 show, there is a “dichotomy that defines Tom Ford – laser-eyed commerce here, lascivious indulgence there”. Sex still sells. Especially the expensive kind.

Since the designer vacated his own label upon its sale, Ford’s shoes have only been filled temporarily. Peter Hawkings, his former protégé, took the wheel for less than a year. Now, the brand is preparing for the incoming Ackermann administration. The founder, it turns out, had a hand in this succession. “He’s the one who called me,” says Ackermann. “Of course we spoke many, many times. I wouldn’t have done it without his approval or benediction. It’s very important for a company when the name is so present.”

He can only say so much about the Tom Ford appointment. His first collection will debut at Paris Fashion Week in March. Throughout the afternoon, though, Ackermann leaves a few glittering clues. Like Ford, he is a designer with “sexy” often affixed to his placard. But it is a different sort of sexy. If Tom Ford’s sensuality is more chemical, Ackermann’s is emotional – a mood, or a gesture, or a moment. This is a man who, by his own admission, “take love very seriously”. To him, the idea of elegance is much more abstract, something rooted in memory. He is almost philosophical. “I met two men in my life: Monsieur Serge Lutens, the perfumier, and recently, Mr Lauder. He’s 92 years old,” Ackermann says. “It’s about their generosity. They’ve been searching for beauty for so many years. They have this quest. The way they speak is beyond elegant, the way they look into your eyes and make you feel part of this. It’s so elegant. They reach out to you.”

If Ford was all glistening glam sex, then maybe Ackermann will lean even further into the power of suggestion – especially in this age of steamy Hollywood style. “There’s no mystery on the red carpet,” he says. “It can be too obvious; there’s nothing to discover. You have everything up in your face.” I counter that this era of menswear could allow men to be more experimental and expressive. He disagrees. “That’s not true. Look at David Bowie, Mick Jagger, Jimi Hendrix. It was authentic. Their life was authentic. Now, it feels more like attention-seeking, screaming louder than the one next to you,” he says, and shrugs. “The world is too loud.”

Ackermann seems to thrive in a Venn diagram between the quasi-traditional and the eccentric. On one hand, he praises London as “very sexy” for its “sense of freedom, and the liberty, and the madness”. But then he points to its more conservative buttoned-up roots, because people wear bespoke suits in the city’s moneyed western enclave. In New York, he loves the energy. But there’s also a fashion legacy that’s to be preserved. “On a Saturday evening, we went for dinner at a very chic restaurant where people still dressed up and made an effort,” he says of his most recent trip to Manhattan. “It was all old businessmen. All in suits, and the women made an effort – whether you like it or not. There were pearls, there were black dresses. It felt so right to look at.” At Tom Ford, perhaps all parts of Ackermann’s universe – the sci-fi, the elegant, the quietly suggestive, the sexy – will collide. “It’s nice not to wear sneakers. It’s nice to stand up straight. It’s nice to feel your shoes are just a little too narrow, and you have to sit differently,” says Ackermann. “The hair is perfect. The perfume is good. The moustache is well cut. It’s kind of a respect to everyone around.”

There is a distinct pressure that comes with two concurrent creative directorships, especially at a time in fashion when, as Ackermann puts it, “everything and everyone is replaceable”. He admits to some nerves. He has to feel that his work is additive. “I’m not easily accepting of any job, and I’ve been declining many things,” he says. “There have been big brands, big companies, really beautiful names, but I didn’t have the feeling that my sensibility would add something to it. It didn’t feel right. But yeah, everything I’m doing now feels right to me.”

And behind him is a social network that the designer holds dear. Timothée Chalamet is part of this core circle. Some of the actor’s most recognisable looks have come from Ackermann (think of the viral majestic silver tailoring on The King’s premiere trail). The two even worked together on a limited-edition hoodie in 2021, a paint-splattered charity piece from which all proceeds went to Afghanistan Libre, an organisation that fights to safeguard women’s and children’s rights in that country. It’s a friendship, and a creative partnership. “We met due to his agent, Brian [Swardstrom], who wanted to meet,” says Ackermann. “The way he enters a room, one can only be seduced. He knew exactly what he was doing; he knows his path. So after five minutes, I knew we would work together, and I would agree to it and it’d make sense. It still makes sense after so many years.” The same can be said for Tilda Swinton, who befriended Ackermann after he declined a red carpet fitting because he was visiting Jaipur. “It must have been around 20 years ago,” he says.“I was going to India with my loved one. When I arrived back in Paris, we shared a moment. She asked why I could not do the fitting. I said I was in love. That’s when we fell in love with each other.”

Chalamet and Swinton are now regular front-rowers at his shows, and their trust in Ackermann allows him to feel safe. “They didn’t give up on me. And there I am, I’m faithful,” he says. “They could have chosen someone different to have made their life easier. But they chose me.”

And that sort of confidence, that trust, has reignited something in Ackermann. “I am content,” he says. “I feel more free than I’ve ever been. And this sort of freedom, you have no fear. You want to do things and continue and I’m well surrounded. I have the luxury of the best friends in the world.”

If Ford was all glistening glam sex, then maybe Ackermann will lean even further into the power of suggestion – especially in this age of steamy Hollywood style. “There’s no mystery on the red carpet,” he says. “It can be too obvious; there’s nothing to discover. You have everything up in your face.” I counter that this era of menswear could allow men to be more experimental and expressive. He disagrees. “That’s not true. Look at David Bowie, Mick Jagger, Jimi Hendrix. It was authentic. Their life was authentic. Now, it feels more like attention-seeking, screaming louder than the one next to you,” he says, and shrugs. “The world is too loud.”

Ackermann seems to thrive in a Venn diagram between the quasi-traditional and the eccentric. On one hand, he praises London as “very sexy” for its “sense of freedom, and the liberty, and the madness”. But then he points to its more conservative buttoned-up roots, because people wear bespoke suits in the city’s moneyed western enclave. In New York, he loves the energy. But there’s also a fashion legacy that’s to be preserved. “On a Saturday evening, we went for dinner at a very chic restaurant where people still dressed up and made an effort,” he says of his most recent trip to Manhattan. “It was all old businessmen. All in suits, and the women made an effort – whether you like it or not. There were pearls, there were black dresses. It felt so right to look at.” At Tom Ford, perhaps all parts of Ackermann’s universe – the sci-fi, the elegant, the quietly suggestive, the sexy – will collide. “It’s nice not to wear sneakers. It’s nice to stand up straight. It’s nice to feel your shoes are just a little too narrow, and you have to sit differently,” says Ackermann. “The hair is perfect. The perfume is good. The moustache is well cut. It’s kind of a respect to everyone around.”

There is a distinct pressure that comes with two concurrent creative directorships, especially at a time in fashion when, as Ackermann puts it, “everything and everyone is replaceable”. He admits to some nerves. He has to feel that his work is additive. “I’m not easily accepting of any job, and I’ve been declining many things,” he says. “There have been big brands, big companies, really beautiful names, but I didn’t have the feeling that my sensibility would add something to it. It didn’t feel right. But yeah, everything I’m doing now feels right to me.”

And behind him is a social network that the designer holds dear. Timothée Chalamet is part of this core circle. Some of the actor’s most recognisable looks have come from Ackermann (think of the viral majestic silver tailoring on The King’s premiere trail). The two even worked together on a limited-edition hoodie in 2021, a paint-splattered charity piece from which all proceeds went to Afghanistan Libre, an organisation that fights to safeguard women’s and children’s rights in that country. It’s a friendship, and a creative partnership. “We met due to his agent, Brian [Swardstrom], who wanted to meet,” says Ackermann. “The way he enters a room, one can only be seduced. He knew exactly what he was doing; he knows his path. So after five minutes, I knew we would work together, and I would agree to it and it’d make sense. It still makes sense after so many years.” The same can be said for Tilda Swinton, who befriended Ackermann after he declined a red carpet fitting because he was visiting Jaipur. “It must have been around 20 years ago,” he says.“I was going to India with my loved one. When I arrived back in Paris, we shared a moment. She asked why I could not do the fitting. I said I was in love. That’s when we fell in love with each other.”

Chalamet and Swinton are now regular front-rowers at his shows, and their trust in Ackermann allows him to feel safe. “They didn’t give up on me. And there I am, I’m faithful,” he says. “They could have chosen someone different to have made their life easier. But they chose me.”

And that sort of confidence, that trust, has reignited something in Ackermann. “I am content,” he says. “I feel more free than I’ve ever been. And this sort of freedom, you have no fear. You want to do things and continue and I’m well surrounded. I have the luxury of the best friends in the world.”