Why Modeling Is, Technically Speaking, A ‘Bad Job’

by ASHLEY MEARS

The day I signed with a modeling agency in New York, a manager sat me down to explain the terms of our working relationship. I was excited to be there, even a bit giddy to be signing a modeling contract, but not so much as to miss the crucial terms: in exchange for exclusive representation and a standard 20% commission from my earnings, the agency would promote and manage my modeling career. As managers to the self-employed, agencies arrange opportunities for models to work in exchange for a cut of their success, but they are not liable for models’ failures. A manager explained as much as he handed me the contract, stating, “Here’s where we don’t promise you the moon and the stars, but we’ll do our best to get you there.”

“Agencies arrange opportunities for models to work in exchange for a cut of their success, but they are not liable for models’ failures.”

The “moon and the stars” is a pretty good way of describing the heights of a modeling career, with top models grossing millions a year, traveling the world, and socializing with celebrities. Yet according to the Occupational Outlook Handbook, models earned an estimated median income of $33,000 in 2011, an admittedly dubious figure given that the Department of Labor lumps together artist and fashion models with product promoters. Earnings among models within an agency are enormously skewed, with some earning over $100,000 a year, while others are as deep as $20,000 in debt. Among the 40 men and women models I interviewed as part of a sociology research project, their incomes ranged from a male model in $1,000 debt at his agency to a female commercial model who grossed $400,000 in a year.

Average earnings are nearly impossible to predict as monthly incomes fluctuate wildly. That’s because, in addition to being poorly paid, work in the cultural industries is structurally unstable and on a freelance, or per-project, contractual basis. These are what sociologists call technically “bad jobs,” akin to other work arrangements in the secondary-employment sector, like day laborers and contingent workers who piece together an irregular living. Such jobs require few skills and no formal education credentials, and the work provides no health or retirement coverage.

However, unlike other “bad jobs,” modeling is high-status work. Though the odds of making it big (or a living at all) are low, modeling is regarded as glamorous work, especially for women. In American popular culture, modeling is celebrated as a prestigious career for young women, any teen fashion magazine will convey as much. Hence my initial excitement at getting a foot in the door.

“But once in, I started to see a work arrangement with large structural inequalities.”

But once in, I started to see a work arrangement with large structural inequalities. As freelancers, models work for themselves, and in contractual terms, bookers work for them receiving commissions for arranging jobs that models secure on their own. This working relationship is more complicated than it might appear, however, because it feels quite different than what it formally is. It feels more like models are precariously clinging to the tastes and preferences of their agents and clients.

Consider, for example, some of the open critiques directed at models by agents and clients throughout their working days. Among the dozens of brutal comments I heard, in interviews and in my own work experiences, a sample: hearing that one has thick ankles, one’s head is asymmetrically shaped, one is too “street-looking,” one has a bad mustache, one’s shoulders are too narrow, one’s scar too prominent, one’s nose is busted, one has too many freckles, one’s *** is too big, and so on. Comments that would otherwise be flagged as sexual harassment in most workplaces are routinely and publicly spoken, propelling models to keep on their toes at all times.

Additionally difficult are the day-to-day ambiguities of trying to keep in favor with very people models pay to look out for them. Glamour combined with low entry criteria means that the model market attracts more people than it should, resulting in overcrowding and steep competition. A steady stream of new faces enters into an agency, while old ones are filtered out, and models can be “dropped” by their agencies with little or no warning. This creates a sense of substitutability — the sense that if you don’t like the terms of market, there are tons of competitors eager to take your place. Taken together, these kinds of experiences put models and their agents on drastically unequal footing.

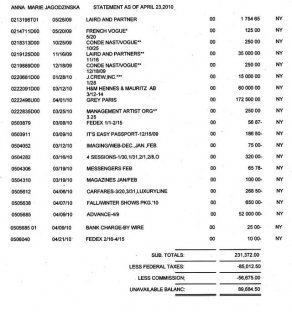

In addition to being a “bad job,” I realized that it’s also an expensive one. Modeling requires extensive start-up and maintenance costs, which agencies incur and deduct from models’ future earnings. These add up quickly. My agencies charged a lot and often for a range of things one would never imagine, from daily bike messenger services to transport books from one client to the next, to the costs of composite cards, and even a charge to include my card in the “Show Package” mailed to Fashion Week casting directors. These expenses were billed against my prospective earnings and automatically deducted from my account. Foreign models can be deep in debt before they ever start castings in a major city, considering the costs of visas and plane tickets. This means models will not see their first paycheck until they book greater than the sum of their debts. After signing my contract in January I began working in magazines, catalogues, and shows by the end of the month. I did not get my first check, for $181.06, until mid-April (prior to this I received voided checks clipped onto a page-long list of expenses, many of which didn’t make obvious sense).

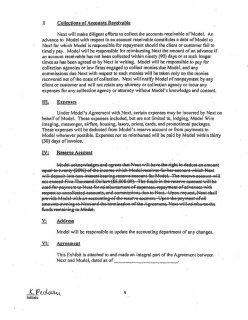

A model who leaves an agency with a debt is legally bound by contract to repay it, though agencies don’t often bother to pursue these debts, since failed models are an unlikely source from whom to recoup losses. Instead, agencies write off negative accounts as a business loss. However, models’ negative accounts will by contact transfer to their next agency should they attempt to model elsewhere, which is unlikely as agencies are hesitant to represent models with existing negative balances from unsuccessful stints at prior agencies. In other words, once in debt, everywhere in debt. What in some ways resembles indentured servitude is a routine part of this independent contractor agreement.

“What in some ways resembles indentured servitude is a routine part of this independent contractor agreement.”

Finally, getting paid can be an ordeal. Payments are slow to come, and they might not come at all. Designers and advertisers are risky liabilities to agencies because they too face a turbulent market. Demand for fashions can change quickly, investors may suddenly pull financial backing, and fashion labels, boutiques, and advertising start-ups can, and frequently do, go bust with little notice. Also common are clients in good financial standing but nonetheless chronically renege on payment.

Some agencies have a policy of advancing earnings to models within one week of the booking. However, if a client fails to pay within a specified time, typically 90 days, the agency will rescind the money from the model’s account until paid in full by the client. Hence, the agency pays its models for doing a job, but if a client defaults on the agency, the model must return the funds. In an effort to reduce their own risks posed by delinquent clients, some agencies pay models only after receiving the client’s payment; should a model want her payment immediately after the job, she’ll have to take an advance on the owed money at a loan rate, typically 5%. And like a bank, the money is recoupable. In other words, if the client doesn’t pay, the model takes the loss, not the agency. Given high expenses and client delinquency, modeling is risky work.

“If the client doesn’t pay, the model takes the loss, not the agency.”

By maintaining an independent contractor relationship, agencies are able to deflect market risks like expenses and delinquent clients as a model’s individual responsibility. Yet in such a relationship, we should expect models to have more say over their expense accounts, the kinds of jobs they have access to pursue, their clients’ payment histories, and, if nothing else, a voice to express these concerns without fear of replacement.

I took a look at her work to date and I'm thinking probably a total of a few million in the bank with all the campaigns and 100's of runway shows?

I took a look at her work to date and I'm thinking probably a total of a few million in the bank with all the campaigns and 100's of runway shows?