You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Marc Jacobs

- Thread starter Kenysha75

- Start date

Bernadette

Active Member

- Joined

- Aug 20, 2013

- Messages

- 1,880

- Reaction score

- 8

Bernadette

Active Member

- Joined

- Aug 20, 2013

- Messages

- 1,880

- Reaction score

- 8

Marc Jacobs on Luxury, Life & Best Moments

Source: YouTube/MarcJacobsInterviews

yesitsdagny

Active Member

- Joined

- Mar 19, 2010

- Messages

- 3,435

- Reaction score

- 2

AlbertNoir

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Dec 9, 2009

- Messages

- 9,814

- Reaction score

- 173

VogueGirl8910

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Apr 14, 2008

- Messages

- 47,976

- Reaction score

- 8,829

dodencebt

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Sep 11, 2010

- Messages

- 5,235

- Reaction score

- 2,973

Bridget Foley’s Diary: Marc Jacobs Talks Runway Communication and Control

The designer discusses the creative decisions behind the staging of his fall 2017 fashion show.

By Bridget Foley on February 11, 2017

“I was anxious to talk rather than write a couple of quick answers.”

So said Marc Jacobs earlier this week regarding a request for his input for a piece on “New York in Transition.”

This story first appeared in the February 11, 2017 issue of WWD. Subscribe Today.

Jacobs is as stalwart a creator as there is in fashion, and as such, was unlikely to take lightly questions along the lines of, “What’s the point of the show?” At this moment of individual and communal reevaluation of “The Collections” Goliath, he is both contemplative and proactive, a joint condition he described in some detail.

He started the conversation with a premise not unlike an academic thesis. “The show is an expression of a thought or an idea about clothes, about a spirit, about a mood. It’s not a presentation of showroom clothes,” he said.

Twenty or so minutes later, he’d touched on his design process, Prince, theater etiquette, a stunning Chanel couture dress (and the girl who wore it), as well as his primary theme — a designer’s right to control the circumstances in which his audience experiences his show.

Jacobs views the runway as a conduit for communication beyond merely a show of what will be on the racks next season. “It’s an esoteric statement,” he said. “Obviously we want to make and sell the clothes that are in the show, so it’s not just for show….But I’ve never been interested in just presenting clothes without considering all the other elements that go into the viewer’s experience.”

While Jacobs wouldn’t elaborate, he implied that the fall collection he’ll present at the Park Avenue Armory on Thursday will differ significantly from his high-intensity spring outing, a raucous rave affair of frenetic pilings. While a dramatic change from one season to the next is typical of his work, fall could prove particularly spare.

“What we’re working toward this season might not seem like the spectacles of the past,” he said. “But in its presentation and in the collection itself there’s still an idea and a message and a thought and a spirit that we try to transmit through the clothes, through the ambiance, through all of our creative choices.”

One thing he knows: The clothes are not necessarily every audience member’s primary focus. “I don’t know what an audience thinks a show should be. It would be unfair to say all press, because nothing is absolute, but it does feel that — in this moment — people pay much more attention to who one’s showing on than what one’s showing. You know, whether it’s the Kendalls or the Gigis.”

He cited as an example the spectacular gown with which Karl Lagerfeld closed his most recent Chanel Couture show, a froth of magnificent pink magic.

“When I saw that beautiful couture Chanel gown I thought, ‘Oh my God, what a gorgeous gown, and the amount of work and the beauty of that dress.’ Yet it seems that everybody was just talking about Lily-Rose Depp in it. The dress was just something on her rather than it being the thing itself. But that’s just the world we live in.

“So to take clothes out of the context of how they’re shown or the music they’re shown to or the experience, it’s so difficult. Everything is part of that experience.”

Not all that long ago, designers could control the experience they wanted to present, control the communication down to the last detail (barring the unforeseen glitch — a model losing her footing; malfunctioning audio or lights). The rise of social media changed that. Today, most fashion shows feature massive audience participation, not always appreciated by the house or other guests. Legions of people take pictures, shoot video and talk through Instagram Stories during shows with an intensity that can impact the overall staging — the lighting, for example. More obviously, that activity impacts how others view the show. Whereas once, one could lose oneself in the creative piece being presented, now, such full submission to the work veers toward impossible when you have to crane past a row of outstretched, phone-wielding arms, and sometimes, view-obstructing torsos, to take in the show.

To that end, Jacobs wants to take back full command of his side of the creative communication. While he can’t control how his audience reacts or how he’s reviewed, he can control what its members see. This season that means a more intimate approach than has become his norm, with a spare set, significantly smaller audience and the request/mandate to keep your cell phone dormant, please. How he plans to enforce that element, he didn’t say.

He sounded serious, invoking the stance of a great creative from a different genre to make his point. “I had the very big privilege of seeing Prince perform just before he died, on New Year’s Eve in St. Barth’s,” Jacobs recalled. “Prince refused to start performing until everyone put their cell phones away. He said, ‘I’m a live performer. I’m playing you music, and if you want this experience you put your cell phones away.’

“In a relationship, there are boundaries. You can convey that if you want to experience a show live, put away your cell phones. But if you allow it, then you’ve allowed the audience to do what they want rather than to see it the way you’d like it to be seen.

“I don’t want to sound angry, because that’s not where it’s coming from,” Jacobs continued. “When I go to the theater, and I’m an avid theatergoer, they say, ‘no cell phones; no recording devices.’ You’re there for a live experience. If you don’t want to watch the live experience, then don’t go to the theater. If you don’t want to watch the live fashion show, then don’t go to the fashion show because it will be online in five minutes after the show.”

He argued that if the primary purpose of a fashion show is as source of online images, then why not do a shoot, dispense with the show and save “the half million-dollar expense or the quarter-million, or whatever it is? This feels like a time to rethink not only what we say but how we say it.” While considering that this approach may prove mere seasonal whim, “right now, these are all things I’m thinking about.”

Jacobs noted that he can’t direct where the audience directs its focus: “If the extent of one’s interest is the celebrity, that’s in the laps of the audience.” Nor did he downplay the significance of the casting, celebrity-driven or otherwise. “Every one of the creative decisions — from music to styling to accessories to shoes to bags to clothes to the girls, the diversity of the casting or the lack of diversity of the casting, everything — it’s all part of the experience,” he said.

As with most forms of creative communication, there are optimum and sub-optimum ways to transmit and receive the message. The best, he maintained, “is when the audience and artist — and I don’t mean artist in a pretentious way, so let’s say the creative force — when the audience and the creative force meet. It’s not when the audience is of one [different] mind.

“It’s a meeting of the moment,” Jacobs continued. “It doesn’t even matter if you absorb the message that the person was transmitting; you feel the experience, rather than you’re just there. It becomes esoteric and sort of philosophical. It’s like when you read a great book and you’re engaged, or when you listen to music and it moves you. The idea of the experience and the choice of words and the choice of sounds, all of that stuff is what creates your experience, your attachment to the moment, the emotion.”

That there is a specific commercial endgame shouldn’t lessen the experience; rather, it informs and often challenges the creative decisions. “We’re left in the end with the clothes and the bags and the shoes and the things that they’ve inspired, and that’s what goes into the stores,” Jacobs said. But the show itself, and the experience of consuming it, results from the integration of all of those creative choices.

“From my perspective, that’s why we have a show,” Jacobs observed. “Whether that means a very elaborate set or whether that’s a refusal to do a set or whether that’s no music — all are concepts or choices, and they have aesthetics and [result from] decisions. Everything is considered. It all goes into the viewer’s experience.”

As with any serious creative communication, that experience might “create a buzz or a tension or start a conversation.” And, Jacobs concluded, “That’s not something you can sell.”

wwd.com

The designer discusses the creative decisions behind the staging of his fall 2017 fashion show.

By Bridget Foley on February 11, 2017

“I was anxious to talk rather than write a couple of quick answers.”

So said Marc Jacobs earlier this week regarding a request for his input for a piece on “New York in Transition.”

This story first appeared in the February 11, 2017 issue of WWD. Subscribe Today.

Jacobs is as stalwart a creator as there is in fashion, and as such, was unlikely to take lightly questions along the lines of, “What’s the point of the show?” At this moment of individual and communal reevaluation of “The Collections” Goliath, he is both contemplative and proactive, a joint condition he described in some detail.

He started the conversation with a premise not unlike an academic thesis. “The show is an expression of a thought or an idea about clothes, about a spirit, about a mood. It’s not a presentation of showroom clothes,” he said.

Twenty or so minutes later, he’d touched on his design process, Prince, theater etiquette, a stunning Chanel couture dress (and the girl who wore it), as well as his primary theme — a designer’s right to control the circumstances in which his audience experiences his show.

Jacobs views the runway as a conduit for communication beyond merely a show of what will be on the racks next season. “It’s an esoteric statement,” he said. “Obviously we want to make and sell the clothes that are in the show, so it’s not just for show….But I’ve never been interested in just presenting clothes without considering all the other elements that go into the viewer’s experience.”

While Jacobs wouldn’t elaborate, he implied that the fall collection he’ll present at the Park Avenue Armory on Thursday will differ significantly from his high-intensity spring outing, a raucous rave affair of frenetic pilings. While a dramatic change from one season to the next is typical of his work, fall could prove particularly spare.

“What we’re working toward this season might not seem like the spectacles of the past,” he said. “But in its presentation and in the collection itself there’s still an idea and a message and a thought and a spirit that we try to transmit through the clothes, through the ambiance, through all of our creative choices.”

One thing he knows: The clothes are not necessarily every audience member’s primary focus. “I don’t know what an audience thinks a show should be. It would be unfair to say all press, because nothing is absolute, but it does feel that — in this moment — people pay much more attention to who one’s showing on than what one’s showing. You know, whether it’s the Kendalls or the Gigis.”

He cited as an example the spectacular gown with which Karl Lagerfeld closed his most recent Chanel Couture show, a froth of magnificent pink magic.

“When I saw that beautiful couture Chanel gown I thought, ‘Oh my God, what a gorgeous gown, and the amount of work and the beauty of that dress.’ Yet it seems that everybody was just talking about Lily-Rose Depp in it. The dress was just something on her rather than it being the thing itself. But that’s just the world we live in.

“So to take clothes out of the context of how they’re shown or the music they’re shown to or the experience, it’s so difficult. Everything is part of that experience.”

Not all that long ago, designers could control the experience they wanted to present, control the communication down to the last detail (barring the unforeseen glitch — a model losing her footing; malfunctioning audio or lights). The rise of social media changed that. Today, most fashion shows feature massive audience participation, not always appreciated by the house or other guests. Legions of people take pictures, shoot video and talk through Instagram Stories during shows with an intensity that can impact the overall staging — the lighting, for example. More obviously, that activity impacts how others view the show. Whereas once, one could lose oneself in the creative piece being presented, now, such full submission to the work veers toward impossible when you have to crane past a row of outstretched, phone-wielding arms, and sometimes, view-obstructing torsos, to take in the show.

To that end, Jacobs wants to take back full command of his side of the creative communication. While he can’t control how his audience reacts or how he’s reviewed, he can control what its members see. This season that means a more intimate approach than has become his norm, with a spare set, significantly smaller audience and the request/mandate to keep your cell phone dormant, please. How he plans to enforce that element, he didn’t say.

He sounded serious, invoking the stance of a great creative from a different genre to make his point. “I had the very big privilege of seeing Prince perform just before he died, on New Year’s Eve in St. Barth’s,” Jacobs recalled. “Prince refused to start performing until everyone put their cell phones away. He said, ‘I’m a live performer. I’m playing you music, and if you want this experience you put your cell phones away.’

“In a relationship, there are boundaries. You can convey that if you want to experience a show live, put away your cell phones. But if you allow it, then you’ve allowed the audience to do what they want rather than to see it the way you’d like it to be seen.

“I don’t want to sound angry, because that’s not where it’s coming from,” Jacobs continued. “When I go to the theater, and I’m an avid theatergoer, they say, ‘no cell phones; no recording devices.’ You’re there for a live experience. If you don’t want to watch the live experience, then don’t go to the theater. If you don’t want to watch the live fashion show, then don’t go to the fashion show because it will be online in five minutes after the show.”

He argued that if the primary purpose of a fashion show is as source of online images, then why not do a shoot, dispense with the show and save “the half million-dollar expense or the quarter-million, or whatever it is? This feels like a time to rethink not only what we say but how we say it.” While considering that this approach may prove mere seasonal whim, “right now, these are all things I’m thinking about.”

Jacobs noted that he can’t direct where the audience directs its focus: “If the extent of one’s interest is the celebrity, that’s in the laps of the audience.” Nor did he downplay the significance of the casting, celebrity-driven or otherwise. “Every one of the creative decisions — from music to styling to accessories to shoes to bags to clothes to the girls, the diversity of the casting or the lack of diversity of the casting, everything — it’s all part of the experience,” he said.

As with most forms of creative communication, there are optimum and sub-optimum ways to transmit and receive the message. The best, he maintained, “is when the audience and artist — and I don’t mean artist in a pretentious way, so let’s say the creative force — when the audience and the creative force meet. It’s not when the audience is of one [different] mind.

“It’s a meeting of the moment,” Jacobs continued. “It doesn’t even matter if you absorb the message that the person was transmitting; you feel the experience, rather than you’re just there. It becomes esoteric and sort of philosophical. It’s like when you read a great book and you’re engaged, or when you listen to music and it moves you. The idea of the experience and the choice of words and the choice of sounds, all of that stuff is what creates your experience, your attachment to the moment, the emotion.”

That there is a specific commercial endgame shouldn’t lessen the experience; rather, it informs and often challenges the creative decisions. “We’re left in the end with the clothes and the bags and the shoes and the things that they’ve inspired, and that’s what goes into the stores,” Jacobs said. But the show itself, and the experience of consuming it, results from the integration of all of those creative choices.

“From my perspective, that’s why we have a show,” Jacobs observed. “Whether that means a very elaborate set or whether that’s a refusal to do a set or whether that’s no music — all are concepts or choices, and they have aesthetics and [result from] decisions. Everything is considered. It all goes into the viewer’s experience.”

As with any serious creative communication, that experience might “create a buzz or a tension or start a conversation.” And, Jacobs concluded, “That’s not something you can sell.”

wwd.com

YohjiAddict

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- May 26, 2016

- Messages

- 3,661

- Reaction score

- 5,226

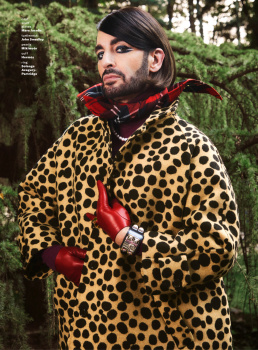

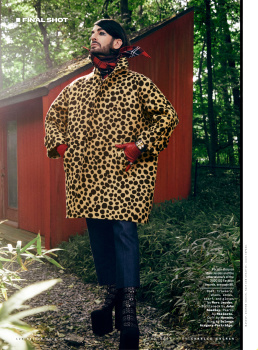

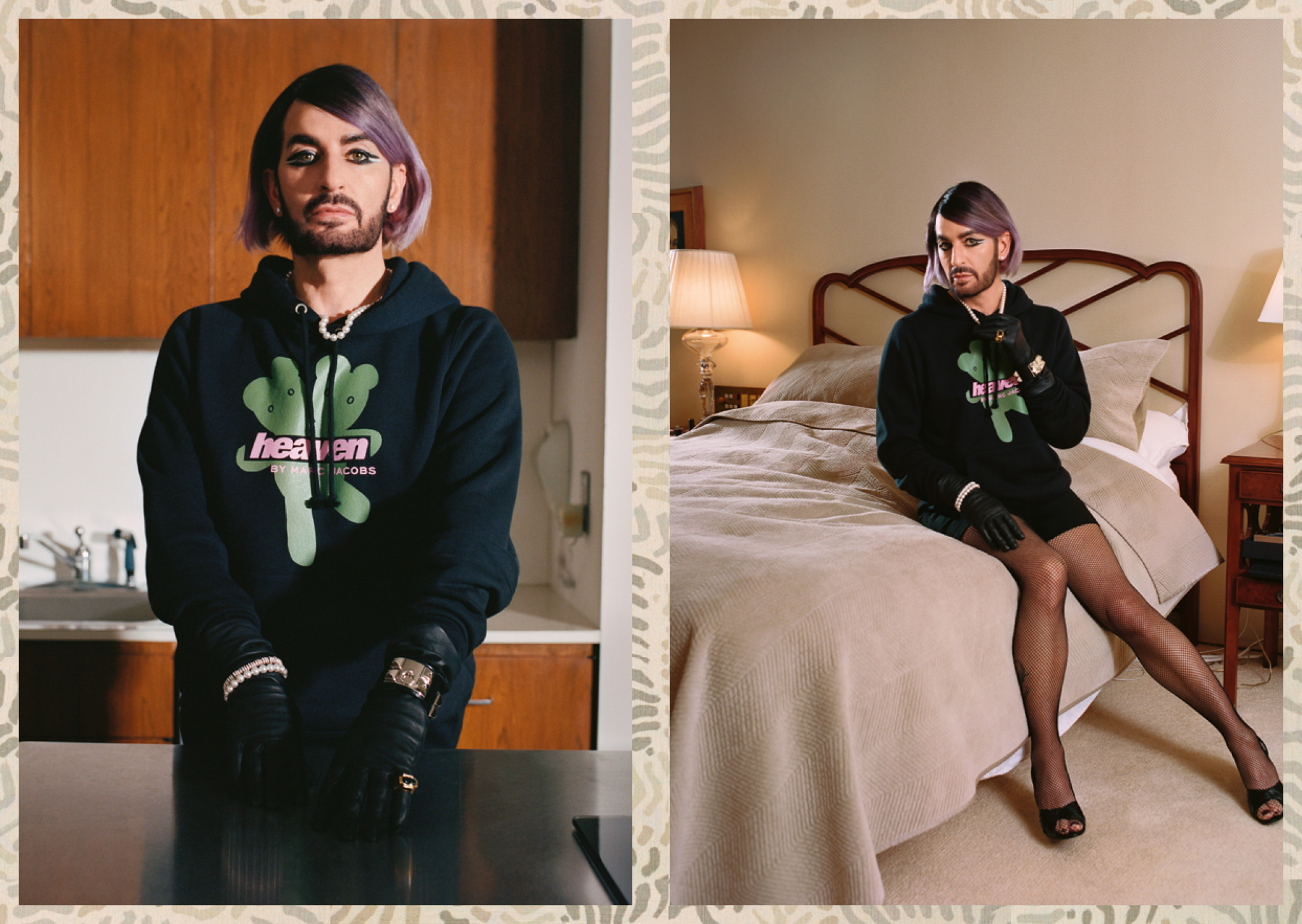

ALL THAT HEAVEN ALLOWS

MARC JACOBS' AMERICAN DREAM

TEXT BY THORA SIEMSEN

PHOTOGRAPHY BY TINA TYRELL

Marc Jacobs and his husband Charly Defrancesco are renting a 1959 ranch-style house in the New York City commuter belt that looks like it could be the set of a Todd Haynes film starring Julianne Moore. It’s a 15-minute drive to their permanent residence, a historic Frank Lloyd Wright–designed waterfront property on the northern tip of Manursing Island, but the longest way around is the shortest way home: their place, where they got married last spring and resided last summer, is still being restored. For now, they are occupying the rental, which suits Jacobs, the 57-year-old native New Yorker who lately favors housewife drag and often suspects he is living a movie version of life. The designer’s worldview holds that memories are sortable by genre, the present can be lent enchantment, and when the unexpected happens, he can chalk it up to missing revision marks on his copy of the script. Some of his closest friends are directors, including Sofia Coppola and Lana Wachowski (who calls him Sissy, short for Sisyphus; the two have matching tattoos based on the myth). The rub is that Jacobs still feels like he has to audition.

“I think it's maybe habitual,” he says, “when someone impresses me or when I want to make an impression, I start to try to change myself to be the person I think they want me to be. And I don't want to do that, but it's that Zelig trigger that goes off: become what you imagine they want and you'll be safe, they'll like you. That part of me never dies. And in fact, I think it's probably a little bit more amplified when it's somebody I really care about. I'm afraid of losing them, so I should curtail my behavior or make sure my conversation is interesting or that I'm paying attention. It's a lot of work for me to just be myself and not the person that I think they want.”

Jacobs’ self-description as a chameleon has always seemed out of keeping with the staunch figure he cuts in the world. He’s a showman, yes. A month before Broadway went dark last spring, the designer sent a group of dancers and models tripping the light fantastic through the drill hall of the Park Avenue Armory. The ensemble was choreographed by Karole Armitage, the downtown ballerina who danced for George Balanchine and Merce Cunningham before leading her own company throughout the 80s. Armitage, the choreographer of Madonna’s “Vogue” and a Tony nominee for her work on Hair (one of Jacobs’ favorite musicals), was the first to appear under spotlight before café tables hosting the show’s attendees. What they saw was Jacobs’ take on a tremendous sweep of fashion history that somehow circumvented nostalgia, as if Jacqueline Kennedy’s Dealey Plaza outfit had gone into a wormhole instead of the National Archives. Models in woolen double-face shifts and coats made way for a dancer shadowboxing in black leather opera gloves, pastel underwear, and pearls. The prevailing opinion was that Jacobs, long the closer of New York Fashion Week, was also the week’s thrumming center, stirring in the audience that most innocent feeling of anticipation.

The following months were a more anxious time. Fabrics for Jacobs’ runway collection were sourced in Italy, the first European country to announce travel restrictions and enter a nationwide lockdown. His design house consequently pared down production of the delayed fall line, which had gone on to Paris showrooms after its presentation in New York. By March, both cities were under stay-at-home orders. Nonessential retailers took action with brick-and-mortar closures and the hell-for-leather pace of the fashion world abruptly slackened. In April, during a livestreamed interview with British Vogue’s editor-in-chief, Edward Enninful, Jacobs acknowledged the unlikelihood of designing a follow-up spring collection. “I aesthetically need to go into something like it’s the last thing I’ll ever do,” he says today. “Because you never know.”

Last year, when a state of emergency was declared in his hometown, Jacobs checked into the Mercer. Like its sister property, Hollywood's Chateau Marmont, SoHo’s luxury loft-style hotel conjures images of an extended stay. Jacobs and his dogs, Lady and Neville, had privacy without the attendant cost. Or the 24-hour room service. The kitchen was closed during the two months that he was one of three guests at the skeleton-staffed hotel. During that time, Jacobs starred in a short film, A New York Story, which lightly fictionalized his quarantine habits. It was directed by his personal assistant, Nick Newbold. To get into character, Jacobs honed his smoky eyes and tried on wigs. Newbold uploaded the results to YouTube.

In a single day, Jacobs can go from looking boyish in sequined Comme des Garçons shorts and a Stüssy shirt (he collaborated with the brand for their 40th anniversary) to surfacing as a Fosse dancer or a desperate housewife. His eyes are a limpid hazel, or green, depending on the color of his eyeshadow. Sober for years, he possesses a sparkly, recovered-addict aura. Having never bought the notion that drugs enhance creativity, the years of his active addiction weren’t altogether lost to dysfunction. “I think that I was very creative while I was drinking and using, and I think I'm more creative now that I'm not,” he says. Jacobs is quick to laugh, never didactic: “I don't use the word ‘advice.’ I don't like advice. I don't give advice. I tend not to listen to it. I like when people share their experiences, and then if that resonates, I know it means something to me.”

I ask him if, in his experience, designers are very supportive of one another. “I have been very fortunate to have some kind of relationship with the designers I respect most,” he says. “There's no living designer I admire more than Mrs. Prada. And I've gotten to know her and she's been very kind, very generous, and very friendly toward me. And I've gotten to know Hedi [Slimane] and Raf [Simons], many designers whose work I respect. None of them have ever put me aside. Karl [Lagerfeld] was very respectful of me. I don't know that many designers do have that relationship, and it's probably because they also have that ego. I think some people who aren't pretentious at all are very guarded, and part of their mystique is to stay away from anyone.”

Jacobs takes a different tack, doesn’t lose anything when he gives of himself. “There's a guy named Ludovic de Saint Sernin whose work I really like. Guillaume Henry, what he's doing at Patou. Eckhaus Latta. I admire Virgil, what he's done. Some designers have a very strange attitude about him, but I just keep thinking back to when I was young and a lot of the old guard would say, ‘That's not fashion, that's not how you do a show, that's not a collection.’ Some designers, especially of a certain generation, look at things by younger creators and they don't realize they're doing exactly what people did to them. It's a very dangerous place to be, when you start to judge and think it's your way or it's wrong.”

While he was quarantined in his Mercer suite, spending the majority of his time safest alone, Jacobs began to feel like his younger self again. He watched the documentary Martin Margiela: In His Own Words and identified with the reclusive Belgian’s childhood reveries. The two designers share a birthday; each learned to sew from their grandmothers. The Leuven-born couturier grew up watching his mother sell wigs out of his father’s salon, whereas the Manhattanite Jacobs saw his parents off to work at William Morris. The latter’s daydreams took wing after his father’s death from ulcerative colitis and his mother’s progression into bipolar disorder. As the eldest of his family, Jacobs drifted unnaturally into the role of caretaker for his two younger siblings. “My mother was in and out of institutions. She remarried very quickly after my dad died and we had this horrible stepfather. We went through a few divorces, marriages,” Jacobs says. “The good that came out of that was I was able to create an alternate reality.”

During his teenage years, he landed in the West Seventies with his father’s mother, who championed his imagination. She lived stylishly, wore low-heeled pumps from Bottega Veneta to spread the gospel of her grandson’s talent around the neighborhood. He was quick to adopt her particulars, needlepointing and acting as custodian of the beautiful objects in their shared unit at the Majestic Apartments, twin Art Deco skyscrapers off Central Park West. His grandmother was not especially sentimental about blood, which made their bond all the more special. “Feeling obliged to see someone because they're family doesn't work for me and it didn't work for her, either,” he remembers. Neither was she the least bit repressive. The city was their backyard, he was going to get hothoused by it anyway.

Jacobs turned sixteen in 1979, the year that Charivari, the avant-garde fashion retailer owned by the Upper West Side’s Weiser family, opened their fourth location, in his neighborhood. As Ingrid Sischy wrote in her final profile, published posthumously in Vanity Fair, “The Weisers’ was a very different fashion moment from the one we are living in now, the one with big global brands, high prices, and a deeply homogenized, even conservative landscape.” The Weisers were entrepreneurs who laid everything on the line, starting and ending in hock. In-between, they created a high-fashion enterprise attracting clientele of the same Versace name stitched into their merchandise. They were the first American stockists of Yohji Yamamoto and the first employers of a teenage Marc Jacobs.

He started in the stockroom. “I begged for the job there,” he says. “I was very convincing. They were the shop that had all these great designers whose work I love. I found myself in a place where I got to meet people who I admired, who also loved fashion, and I learned to ask questions.” On one occasion, the precocious stock boy consulted with Charivari regular Perry Ellis regarding his future and was encouraged by the designer to attend Parsons after he graduated from the High School of Art and Design. The neighborhood boutique was also where a schoolboy Jacobs met his first boyfriend, a customer in his thirties named Robert Boykin.

Boykin was a front owner of the fabled club Hurrah on West 62nd Street. Opened as a disco in 1976 but revamped as a rock club when the nearby Studio 54 opened months later, Hurrah retained its edge. The mirrored walls surrounding the dance floor, vestiges of its disco beginnings, can be glimpsed in David Bowie’s “Fashion” music video. As the teenage boyfriend of Boykin, Jacobs mixed awkwardly with the voluptuary crowd. He was dazzled. “I just can't imagine not wanting to know the history of New York, who was who, how it came to be, and what the scene was like,” he tells me.

Through Boykin, Jacobs also learned about a particular way of life in the American South. “He was from Mobile, Alabama. I was 16 and he was 34, and I was a very effeminate little Jewish boy and his family was far from Jewish. I had a lot to navigate, but they never did. It was me thinking that they would have to deal with that and they were really open. I would say they accepted their son's choices. His father's side of the family was so loving. I remember they took me fishing, hunting for deer.”

Could he shoot?

“No, I learned how to, but I couldn't shoot an animal and they'd be like, ‘Oh, well you're not going to be one of those New Yorkers who tells us it's wrong to shoot an animal, and I was like, No, I just can't do it, you can do whatever you want.’”

Boykin and Jacobs were together for nine years up to Boykin’s death from AIDS-related complications in 1988. Their relationship, often inscrutable to others, was for Jacobs to make sense of: “I just had this fantasy. This was going to be my part in the new movie, the next scene was: Marc gets a boyfriend, they have this physical relationship. I had this glamorous script written for me as the young boyfriend of Robert Boykin. And the reality of it was I wasn't okay with intimacy. He allowed me to live a life that I wanted. He was kind of like a dad to me, a brother to me, a best friend, a protector.”

Throughout their relationship, Jacobs was exceptionally driven. He acted on Ellis’ suggestion, enrolling at Parsons for fashion design. “I was a really good student,” he says. “I had a couple of friends in school. Tracy Reese and I were probably the most motivated students in my class. We used to do our homework together and we would go way far beyond the call of duty. If we had an assignment to do twelve sketches for Mrs. Abrams class, Tracy and I would do 36.” Jacobs graduated in 1984 with a winning senior thesis of op art sweaters handknit with his grandmother, earning him Design Student of the Year and the Chester Weinberg and Perry Ellis Gold Thimble awards. His achievements also secured him a longtime business partner in Robert Duffy, a former buyer for Bergdorf Goodman and then an executive at Reuben Thomas, who founded Jacobs’ eponymous line with him upon his graduation.

“When I was a young person, I just couldn't get enough. Anything that I was interested in, or that was an offshoot of something I was interested in, I wanted to accumulate experience with or knowledge about,” Jacobs says. The designer, who trailed his grandmother on trips to Bergdorfs and ate into the narcotic feast of his city by night, was uniquely equipped to arrest the moment. He earned the CFDA Perry Ellis Award for New Fashion Talent in 1987, prompting his and Duffy’s installation at Ellis as, respectively, vice president of women’s design and president. In 1992, Sonic Youth shot their music video for “Sugar Kane” in the Ellis showroom featuring Sassy magazine intern Chloë Sevigny in her first acting role. The video captures the process of Jacobs mounting his spring 1993 ready-to-wear collection—Seventh Avenue versions of beanies, butterfly crop tops and baby-doll dresses—which got him fired from Ellis after it debuted and stoked his reputation as an iconoclast. The dismissal came with a financial windfall, which Jacobs and Duffy poured into the creation of Marc Jacobs International Company, L.P.. The grunge label stuck.

“Everything’s a label now,” Jacobs says. “When I was younger, we'd go to Bleecker Bob's and I'd buy B-52's, X-Ray Spex, whatever music I was into as a teenager. And then later in life, when there was Tower Records, everything was divided. They had those little plastic things that would say ‘alternative’ and I just thought, isn't everything an alternative to something else? I never thought of it as ‘grunge.’ It was just the music I liked at the time.” His first ad for his namesake line was simple: Kim Gordon onstage in London wearing his dress, shot by Juergen Teller. It ran in stylist Joe McKenna’s magazine Joe’s, which had a limited run (two issues ever published, six years apart) and featured the Virgin Mary on its inaugural cover.

The ad set the tone for Jacobs’ approach with Teller. Campaigns would come together loosely, the photographer was given carte blanche. Jacobs explains, “One of us would find someone of interest, who felt like they were a part of our world, and then find a situation that was comfortable for that person to be in.” Sometimes discomfort was more interesting to them. Jacobs and Teller both doffed their clothes for the brand’s ads themselves, the designer for his men’s fragrance, Bang, the photographer for a self-portrait in bed with the actress Charlotte Rampling (he kept on a pair of Marc Jacobs silver shorts). Victoria Beckham appeared in an ad that featured only her tanned legs jutting out of an oversized carrier bag. “I think people thought that I was being like others who were turning their nose up. I didn't look at it that way,” Jacobs says of casting the pop star and fashion designer. “She was coming to see my work and she was interested in fashion and I liked her. I met with Victoria in Paris, and I said, ‘There is a part of this that will be taking the piss, but I really want you to be in the pictures, Juergen wants you to be in the pictures, but you need to understand that Juergen doesn't do glamorous pictures. There isn't light, there isn't going to be makeup. Nobody's going to be making fun of you, but we need you to have fun with us.’”

Teller’s collaborations with Jacobs, on every print ad from 1998 until 2014, let fans in on the fun. Their success was in creating an identifiably unconventional and endearing muse and customer. As Sarah Nicole Prickett wrote of the Marc Jacobs woman in 2015 in T: The New York Times Style Magazine, “She’s the guest at the party who everyone looks at like they know her but can’t think from where, and who looks around like she’s never known anyone. She appears more out of time than out of place: Her skirt is calf-length and conservative with unsexy heels, but her T-shirt is sequined and see-through.”

Jacobs’ other job at the time was another story. Established in 1854, Louis Vuitton had sold bags to the beau monde throughout numerous revolutions in travel. As artistic director of Vuitton from 1997 until 2013, Jacobs oversaw a major revival of the historic French house known prior to his arrival for their luggage and accessories. He was the legacy house’s first ready-to-wear designer. “I had a struggle when I went to Vuitton. I wasn't wanted there. I mean, Mr. Arnault wanted me and he gave me the job,” he says, referring to Bernard Arnault, chairman and CEO of LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton. “And eventually I think Yves Carcelle,” the late longtime LVMH executive, “really respected what I did.”

A crisp coat and skirt from Jacobs’ first show for Vuitton now belong to The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute. The collection debuted at Paris Fashion Week in the spring of 1998. Cathy Horyn, who was hired as the second fashion critic at The New York Times later that same year, tells me, “I doubt that most of us realized we were watching someone establish an aesthetic at Vuitton, but that's what Marc was doing, in the beginning. He was giving a brand, famous for luggage and a logo, a sartorial look. From scratch. At the same time, he was jumping—feet first—into a very tough French business world. It must have been a huge, and sometimes painful, learning experience.”

During his tenure as artistic director, Jacobs achieved the high-wire act of honoring tradition, eliciting a response, and leveraging enough room to stay mischievous. His shows for Vuitton were never stuffy, always grand. There was the time he had models climb off a custom-built steam locomotive in the Cour Carrée du Louvre followed by uniformed porters holding crocodile hat boxes for their Stephen Jones’ millinery. Or when he craned working escalators into the same courtyard so that models in checkerboard prints could descend onto a chess grid. Or when he wanted something demure the season after he refined fetishwear, sending models in laser-cut lace draped in organza around a carousel inspired by the one in the Tuileries Garden.

“I saw Paris as something out of a film,” Jacobs says. “It all felt scripted. But I love that movie. I loved the sets in that movie. I love the lighting in that movie.” He loved the pace of that movie; life was slower in Paris. He settled into his well-appointed three-story garden apartment near the Champ de Mars, hung Ruschas from the walls. Mostly he went to work. On Mondays he had meetings with LVMH executives. “It was such an odd and beautiful relationship with Mr. Arnault. I would always look for his approval. I cared less and less and less about everyone else's approval. I was like a son who wants his dad to say, ‘Good job,’ that's what I wanted from him. As opposed to the way sometimes things could be handled, which was to create competition, make designers competitive with each other. I could see through that.”

Horyn says that Jacobs’ collaborations with the artist Takashi Murakami, starting with Vuitton’s spring 2003 collection, were a turning point: “It framed a luxury brand in a new and different way, and his timing—a strength with Marc—was dead-on. It anticipated the obsession of the art world with fashion, and vice-versa. He truly helped to lay the visual groundwork at Louis Vuitton—Nicolas Ghesquière has said as much.” She adds, “He was also doing some fantastic Marc Jacobs shows. When you think about it, Marc is ripe for a museum exhibit that looks at those years, and includes Marc Jacobs, right up through the Armitage collaboration this past February. That would be important for Marc's legacy, and thrilling to see.”

Last year, Jacobs hired the Australian-born, Brooklyn-based Ava Nirui, a former digital editor at Helmut Lang known for her bootleg designs, as special projects director. “I really think the best ideas come for me through collaboration. I don't need to own them,” he says. Their first special project together is Heaven, a diffusion line of Marc Jacobs geared toward the teenager reading Lolita and pining after actor James Duval in Gregg Araki’s “teenage apocalypse trilogy.” Mirrors are hung from closed doors, a magazine weighs on a trampoline, and a landline telephone is on the floor in the teen rooms dreamed up to showcase the line. The clothes are sleek and slacker-friendly, the perfect back-to-school wardrobe for a generation who may never go back to school as they knew it. Shoichi Aoki, the photographer and founder of the Japanese street-fashion magazine FRUiTS, shot a lookbook for the collection in Tokyo. Jacobs says, “I feel like my history has inspired some people, like Ava, who has a genuine connection to another generation. What I can do, and what I think is right to do, is let that happen and not try to manage that.” For a launch party, they screened Araki’s film Nowhere at a drive-in in Brooklyn, with the musicians Dev Hynes and Aaron Maine (Porches) among the tailgaters.

Jacobs doesn’t miss traveling. Laying plans for the Frank Lloyd Wright house keeps his imagination busy. “Home, that's what I care about most. More than fashion, more than anything. My complete obsession right now is to make this next home, this home of ours, the place that we'll be forever. Which is my attitude always, but this is it. This is going to be the final chapter. And I don't mean that in a negative way. I'm not planning to sit in a rocking chair,” he says. He’s shown restraint in collecting art since his recent everything-must-go Sotheby’s auction, though he did jump at an offer of a Sam McKinniss painting of Winona Ryder as Lydia Deetz that he’s admired for years (“Not only is Winona really special to me, and not only is Beetlejuice one of my go-to inspiration movies, but that painting was the reason I investigated an artist named Sam McKinniss. I got everybody turned on to Sam.”)

McKinniss, who met Jacobs in 2016 at an exhibition of the painter's work, tells me, “Marc Jacobs was the most interesting person in the world when I was in art college. To me, at least, as well as a lot of other people. I remember seeing the documentary about his time working for Louis Vuitton, and shopping at Marc by Marc Jacobs, having crushes on the shop boys there. I really believe in his ethic, the fantasy, the product, the humor. Marc’s self-reflexivity is very funny, but it’s also intelligent, sexy, and it works.”

Three days after Election Day, at the rental house in Rye, Jacobs sits at a dining room table with several of his colleagues.

“Will you be dressing our future vice president?” makeup artist Andrew Colvin asks him.

“We've already reached out,” Jacobs’ publicist Michael Ariano replies.

“You have? God, Michael, you are so on it,” Jacobs responds, adding, “Mrs. Obama wore a few things.”

In conversation, he stays open, moves on in nothing flat. It’s the Jacobs way. “I think there's a kind of audacious, active pleasure I get out of saying: Yeah, I have had three hair transplants. Yeah, I go to a dermatologist to get filler. Yeah, I have been in rehab. Yeah, I was a heroin addict. Yeah, I had orgies. Yeah, my mother was in Bellevue. Come for me now,” he tells me. In 2015, when he was new to Instagram, he accidentally posted a nude selfie meant for a “hot Brazilian” to his account with the caption: “It’s yours to try!” Screenshots are forever, but so is Jacobs’ ability to take things in stride. Shortly after, he introduced t-shirts featuring the slogan in his stores. He continues, “Half the gay designers out there are on Grindr. They just won't admit to it. I used my picture and my name. Do you know how many people would say, prove that you're Marc Jacobs. I'd have to do things like hold up four fingers and send them a picture to prove that I was who I said I was. Hilarious. What, do you become a public figure and you don't have sex anymore? You don't have desires? I could think of so many people who came before me who hid the fact that they used cocaine, who hid the fact that boys were coming to their room, who hid the fact that they were dressing up in women's clothes. I'm just going to tell it like it is.”

Jacobs describes meeting Defrancesco through mutual friends: “I was with a group of people and he was the only one who got what I was saying.” It was dialogue from the same script, a modern romantic comedy. They got engaged on Defrancesco’s birthday in 2018 at the Chipotle on West 13th and 6th Avenue, married quietly at home, then threw a lavish party for seven hundred guests at the Seagram Building in Midtown. Guests were gifted Marc Jacobs hoodies that read “Don’t Float Away” embroidered with a pair of sea otters. The slogan is also inscribed on the inside of Jacobs’ gold wedding band. “At some point early on we started saying ‘don’t float away’ to each other in a cutesy little voice. It is the most cliché and silliest thing, but we love the videos on YouTube of otters holding hands.”

Jacobs knows from his favorite book that young men don’t “drift coolly out of nowhere and buy a palace on Long Island Sound.” The designer, who has kept daisies fresh up to this century’s twenties, found a muse early in Fitzgerald’s Buchanan. The house on Manursing Island will afford the husbands a view of the estuary and the Connecticut coastline. At the moment, Jacobs is seeing himself clearly: “I was thinking about this actually in the shower: What's different about me now? Why do I feel more desire to express myself and why has that self-expression come to the place that it has? When I got sober, I just absolutely refused to be ashamed. After so many years or situations where I felt bullied in some way, I just wasn't going to allow that anymore. I wasn't going to be a victim. Any shame I felt would not be because I thought you made me feel that way, because that isn't possible anyway. I could own my own feelings. I'm not going to be told by someone else what normal means.” That’s good advice, even if he didn’t mean it that way.

SSENSE

Similar Threads

- Replies

- 48

- Views

- 12K

- Replies

- 73

- Views

- 11K

- Replies

- 103

- Views

- 27K

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)