Does a Prada Sale Make Sense?

The Italian brand may no longer be a luxury leader, but it is still an attractive asset for prospective buyers.

By BoF Team January 31, 2020 17:58

After bubbling up for months, speculation mounted during the recent men's fashion month that the Italian luxury goods maker was exploring a sale to Kering, LVMH or even Richemont. Reports also spread that designer Raf Simons was set to join Prada Group SpA in some capacity.

The rumours followed a small but notable change in the parent company's structure this past October, when it bought four key Prada brand stores in Milan that were previously owned by the Prada family and operated through franchise agreements. Any future acquirer would want these stores, especially its first location open since 1913. Was this consolidation a sign of something to come?

A representative for Prada denied a forthcoming sale and declined to comment on Simons’ potential arrival. Representatives for Kering and Richemont declined to comment. At its annual results presentation this week, LVMH Chairman and Chief Executive Bernard Arnault brushed off the rumours when asked.

Prada’s Chief Executive Patrizio Bertelli, who controls 80 percent of the business with partner and designer Miuccia Prada, has for years rebuffed any intentions to sell the company.

Even if all the recent Prada related speculation is just that, the luxury brand’s future may depend on plugging into one of the all-powerful luxury conglomerates.

Prada, the brand, is bigger than Prada, the business, making it an attractive asset for prospective buyers.

Prada, the brand, is bigger than Prada, the business, making it an attractive asset for prospective buyers. Prada’s logo may not have quite the same name recognition as the Louis Vuitton "LV," but the brand is one of the oldest and most respected Italian houses in luxury. Miuccia Prada’s men’s and women’s collections continue to earn praise from critics and creatives. And the company has potential to grow, as it is still much smaller than many of its heritage peers including Gucci and Louis Vuitton.

“It’s one of the biggest luxury brands in the world: If they make a phone call to Avenue Montaigne or to the headquarters of Kering, they will have an answer,” said Mario Ortelli, managing partner of luxury advisory firm Ortelli&Co. “But who decides the future are Miuccia Prada and Patrizio Bertelli.”

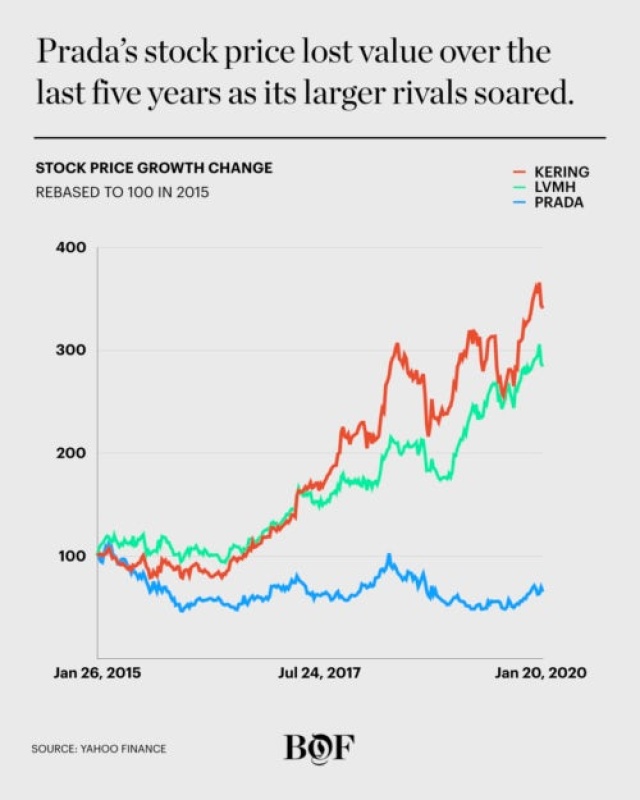

Indeed, the business is deeply personal to Prada and Bertelli, and they are not facing any external pressure to sell it. And with the share price down 35 percent over the last five years, the timing isn’t ideal now either.

But Prada has suffered from strategic missteps in recent years, and would benefit from the management muscle that a big conglomerate would bring.

Despite efforts to adapt to industry shifts in distribution and communications, Prada was too late to recognise these key changes, investing in additional stores when competitors started prioritising online sales.

Merchandising has also been a problem. Despite having the historical bona fides to lead the latest streetwear luxury wave — the 1990s hit Linea Rossa line established the movement then — the brand cut back on entry-level price point products just as competitors established themselves in the key sneaker and athleisure categories and courted Chinese shoppers.

By the time Prada relaunched its Linea Rossa line in 2018 and partnered with Adidas in 2019, the luxury streetwear trend was already well-trod territory for Louis Vuitton and Balenciaga.

Prada’s recent challenges first became painfully apparent in 2016, when revenues decreased 10.3 percent on constant exchange rates to €3.2 billion, down from €3.5 billion in 2014.

A turnaround plan is ongoing, with focus on moving more sales from wholesale to direct retail, reducing markdowns and enforcing a greater control over prices. In 2018, Prada started an invitation-only pop-up club series called Prada Mode, as part of an effort to extend the community of creatives around the brand.

But the financial results are still underwhelming. Revenue in the first half of 2019 was flat year-over-year for the group and for Prada the brand, which represents more than 80 percent of sales. Retail sales decreased after the brand stopped all promotions and discounts in January 2019, but full-price retail sales grew slightly. Handbag sales were flat. Meanwhile, the company closed 10 stores and opened 11, and is planning about 50 store renovations and relocation projects.

Prada’s wholesale revenue was more positive in the period, as it continues to work with multi-brand e-commerce players like MyTheresa and Net-a-Porter, partners only since 2016. But a wholesale rationalisation strategy kicked off in the second half of 2019, reducing the amount of product available via these retailers by 50 percent for the spring 2020 season, according to Bertelli’s remarks to analysts in August 2019.

Some analysts have recommended an organisational refresh, including new leadership, as well as new approaches in merchandising and branding.

But regardless of what headway Prada is able to make, operating independently in the luxury business is an increasingly uphill battle as the industry continues to consolidate under the umbrellas of LVMH, Kering and Richemont, which wield greater negotiating power with outside partners and have strong networks of executives and designers.

Even Moncler, with its double-digit, Genius project-fueled growth, has been the subject of sale rumours.

Surviving independently requires risk-taking, Ortelli said, and risks are harder to take when the competitors are so far ahead. “To take market share away from the other major brands like Gucci, Louis Vuitton and Saint Laurent is very difficult when, as in the last years, they are having a great momentum” he said.

With the support of LVMH or Kering as a parent company, however, Prada could accelerate its modernisation efforts, taking advantage of those companies’ more developed e-commerce capabilities and tapping into a network of trained luxury executives who would bring new leadership to the company. And it could benefit from less public exposure as it takes time to invest for long-term success.

What happens after Miuccia, whenever that may be?

All of these concerns are secondary to the main question looming over Prada: what happens after Miuccia, whenever that may be? The designer has been the creative force of the business since 1978 — its entire expansion into hit handbags, footwear and ready-to-wear. And historically, the transition at a namesake brand from the founding designer to successors is a turbulent one. Valentino Garavani’s first successor, Alessandra Facchinetti, butted heads with management and left after two seasons. In the years after Yves Saint Laurent’s death, the brand was challenged and ebbed and flowed under a series of different creative directors and chief executives.

“For [namesake] brands, the change of the founding designer is always the most complex phase, and it requires a long time to be realised successfully,” said Ortelli. “If you are an independent company you are in the spotlight. If you are part of a group you can more easily take time.”

Prada and Bertelli, now both in their 70s, have not publicly addressed succession plans and did not appear to have a strategy in place until their son Lorenzo Bertelli joined the company as head of digital communication in September 2018. His arrival signalled that the company may keep the business in the family moving forward, and he may be ambitious enough to lead a more effective turnaround independently.

“A brand like Prada has the size and the strength to survive independently,” said Ortelli. “It is a question of willingness.”