You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

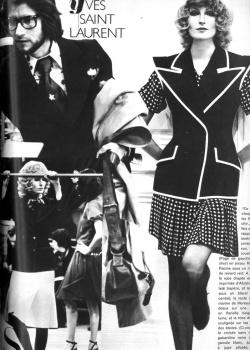

1936-2008 Yves Saint Laurent

- Thread starter softgrey

- Start date

softgrey

flaunt the imperfection

- Joined

- Jan 28, 2004

- Messages

- 52,984

- Reaction score

- 413

boomer-

i have come to think that it's better that they leave it off now that Yves is not designing anymore...

it's not Yves Saint Laurent without Yves...

and maybe that is really how it should be, you know?

maybe it's for the best...

plus- i really wouldn't want any of my original vintage pieces confused with the commercial stuff that is going on there now...

it's a good way to separate them, in a way...

i have come to think that it's better that they leave it off now that Yves is not designing anymore...

it's not Yves Saint Laurent without Yves...

and maybe that is really how it should be, you know?

maybe it's for the best...

plus- i really wouldn't want any of my original vintage pieces confused with the commercial stuff that is going on there now...

it's a good way to separate them, in a way...

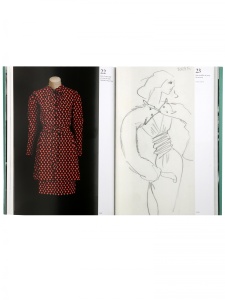

Date: ca. 1970

Medium: cotton

Dimensions: Length at CB: 52 in. (132.1 cm)

Credit Line: Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Youseff Rizkallah, 1986

metmuseum.org

Medium: cotton

Dimensions: Length at CB: 52 in. (132.1 cm)

Credit Line: Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Youseff Rizkallah, 1986

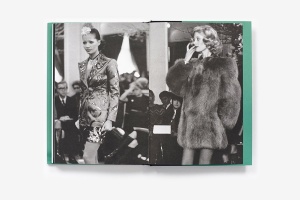

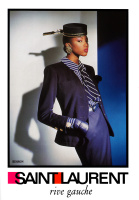

Yves Saint Laurent's Rive Gauche line for women debuted in 1966, with menswear following in 1969. In promoting ready-to-wear clothing, Saint Laurent successfully outfitted a new group of consumers with his designs. In this example, Saint Laurent showed how a functional garment, a basic man's raincoat, could be adapted, enlivened and made fashionable. Men's clothing in the 1960s incorporated colors far beyond the traditional muted palette and the teal blue of this raincoat illustrates how the "peacock revolution" of that decade extended into the 1970s.

metmuseum.org

Last edited by a moderator:

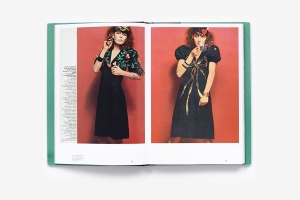

Date: ca. 1969

Medium: cotton

Dimensions: Length at CB (a 30 1/2 in. (77.5 cm) Length at CB (b

30 1/2 in. (77.5 cm) Length at CB (b 43 in. (109.2 cm)

43 in. (109.2 cm)

Credit Line: Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Kay Kerr Uebel, 1987

metmuseum.org

Medium: cotton

Dimensions: Length at CB (a

30 1/2 in. (77.5 cm) Length at CB (b

30 1/2 in. (77.5 cm) Length at CB (b 43 in. (109.2 cm)

43 in. (109.2 cm)Credit Line: Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Kay Kerr Uebel, 1987

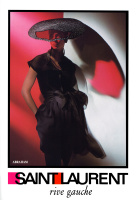

Yves Saint Laurent's Rive Gauche line for women debuted in 1966. In promoting ready-to-wear clothing, Saint Laurent successfully outfitted a new group of consumers with his designs. One of his successful looks for Rive Gauche was the "safari" jacket, a feminine version of what a big-game hunter might wear while traveling in Africa. In this example, Saint Laurent paired the jacket with trousers to create one of the pantsuits he regularly offered for women's wear. He also used a dyed textile that resembled handmade tie-dyed garments of the 1960s, which illustrates how counter-culture styles influenced mainstream fashion from established design houses during this period, a reversal of previous norms.

metmuseum.org

Last edited by a moderator:

FrenchCactus

Vogue Paris Intern

- Joined

- Mar 27, 2006

- Messages

- 2,744

- Reaction score

- 0

softgrey

flaunt the imperfection

- Joined

- Jan 28, 2004

- Messages

- 52,984

- Reaction score

- 413

saw a girl today wearing an oversized dark green coat with black trim and black velvet under the sleeves and collar...

she looked so great and i just had to ask her...

is that vintage YSL...

she was very surprised and said it was...

frankly- it was the most modern coat i have seen in a very long time and i congratulated her on her wonderful find...

those vintage pieces really are better than anything going on today...

hands down...

she looked so great and i just had to ask her...

is that vintage YSL...

she was very surprised and said it was...

frankly- it was the most modern coat i have seen in a very long time and i congratulated her on her wonderful find...

those vintage pieces really are better than anything going on today...

hands down...

dancorpse

Active Member

- Joined

- Sep 4, 2008

- Messages

- 1,879

- Reaction score

- 59

^i think you should post a picture.

taz should know, i guess.

and you can check jalou gallery, here :

http://patrimoine.jalougallery.com/lofficiel-1000-modeles-numero_22-2002-detail-28-1115.html

this issue has all the YSL collection ...

The issue is amazine!! Anyonw know s this downloadable? Seems it can only be viewed online...

VogueGirl8910

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Apr 14, 2008

- Messages

- 48,027

- Reaction score

- 8,808

nanker_phledge

Active Member

- Joined

- Sep 23, 2005

- Messages

- 1,257

- Reaction score

- 3

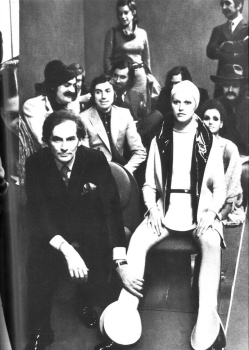

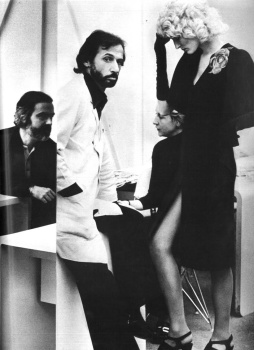

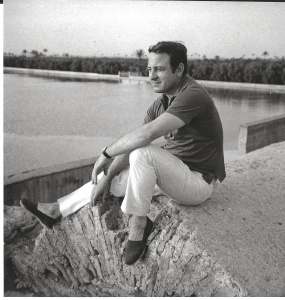

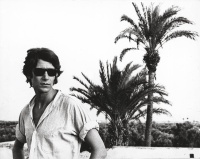

I just stumbled across this picture of Salvador Dali with (apparently) Yves Saint Laurent and yet the guy in question looks NOTHING like him whatsoever...Am I the only one who feels weirded out by this picture (I've done a reverse image search and yet it's listed everywhere as being him)...I'm quite familiar with his physical appearance as a young man and his personal story, and yet I can't keep my head around it, it just doesn't look like him. Anyone else feels the same way ?

source : kinoimages.com

source : kinoimages.com

Last edited by a moderator:

nanker_phledge

Active Member

- Joined

- Sep 23, 2005

- Messages

- 1,257

- Reaction score

- 3

Thank you so much.

AngelLover

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Jun 17, 2009

- Messages

- 1,338

- Reaction score

- 173

MissMagAddict

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Feb 2, 2005

- Messages

- 26,621

- Reaction score

- 1,353

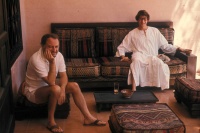

source | nymagWhat Pierre Bergé Taught Me About Fashion

Cathy Horyn September 9, 2017 8:03 pm

Timing is everything in life, and so it is in journalism. I had the good fortune of becoming a fashion writer in 1986, when the industry was still dominated by privately owned houses founded by extraordinarily tough but generous individuals — men like Yves Saint Laurent and his lifelong business partner Pierre Bergé; Valentino; Giancarlo Giammetti; and Oscar de la Renta. There was a second ring of designers whom I adored, and relied on for gossip and insight, like my friend Fernando Sánchez; and there were the editors who were a school unto themselves — no one more so than the late John Fairchild, whose family owned and ran Women’s Wear Daily during the prime fashion decades of the 20th century. I never worked for John, but we became friends later, after he had retired.

Because these people were part of my development as a fashion writer, it doesn’t take much for a memory to be triggered, and then out rushes a whole series of them. But here I want to tell just one story, about Bergé, who died this week at age 86. It not only illustrates an aspect of his personality perhaps not addressed in the tributes to him, but it also spotlights a crucial difference in journalism and the fashion world between then and now.

In 1999, Adam Moss, then the editor of the New York Times Magazine, asked if I would write a profile of Saint Laurent. He and Bergé were selling the ready-to-wear and fragrance portions of their business to Gucci Group, while retaining the infinitesimal haute-couture house for themselves. It was one of those watersheds in fashion; Gucci and LVMH were battling for supremacy, acquiring old houses, and with Tom Ford’s star power at its absolute zenith, the media focus was on him and Gucci, leaving those two old Paris lions deeply in the shadows.

I rang Bergé at his office in the Avenue Marceau and proposed the story. I didn’t know him all that well — we had met two or three times — but he agreed immediately. That generation of designers was extremely competitive, so the idea of stealing back some of the limelight was probably attractive, and of course, it was another chance to perform the role Bergé had played for four decades: protecting Yves and their legacy. Plus, as everyone knew, he hated Ford.

Bergé told me I could have carte-blanche access to Yves and all their friends. Not only did I spend unfettered time with Yves at his home on the Rue de Babylone, with its jaw-dropping living room filled with masterpieces — a Goya, Picassos, Matisses, etc. — and Jean-Michel Frank furniture, but I also spent time with most of the members of the Saint Laurent entourage: Betty Catroux; Loulou de la Falaise and her husband, Thadee Klossowski; Madison Cox; and Fernando. I also interviewed Karl Lagerfeld in a long, wonderful, late-night session on the terrace of his house in Biarritz. That was the only time, as far as I know, that Lagerfeld spoke publicly about his great friend Jacques de Bascher, and Bascher’s relationship with Saint Laurent, which many in the Saint Laurent circle viewed as destructive.

I had the time of my life, and I got a great story — thanks to Bergé. He simply was not afraid of what I would hear. Well, why would he be? He had seen everything with Yves, who could be incredibly destructive, ingesting everything — including 150 Peter Stuyvesant cigarettes a day (a fact supplied by Bergé). He also knew that Yves’s tremendous willpower, his sensitivities and his terrors, were elemental to his genius, and were part of what separated him from Ford. So he wanted me to see and hear everything.

I remember sitting with Fernando one night in the kitchen of his fabulous apartment in New York (it had a ballroom) as he explained these two complicated, forever entwined men. He told me it was not true, as many then believed, that Bergé controlled Yves; they were accomplices. “They will die with their hands on the other’s throat,” Fernando said. “They would like to be each other’s victim, but there is no victim here — and I would tell it to their faces: ‘You’re both monsters.’”

Today, the fashion business is so controlling and fearful that journalists are almost never given that kind of access anymore. Yves didn’t ask for photo approval; he sat for his portrait at home, and that was that. When the piece was fact-checked, Bergé didn’t ask for one thing to be changed. I saw him quite often after that, sometimes at the Café de Flore — he sat just inside the main door to the left — and he was always friendly, if not overly warm, toward me. I felt strangely that I owed him something, but of course I did not. It was just old-fashioned, professional respect that we had in common and, I like to think, enjoyed.

Last edited by a moderator:

Similar Threads

- Replies

- 698

- Views

- 348K

- Replies

- 68

- Views

- 10K

- Replies

- 65

- Views

- 11K

- Replies

- 19

- Views

- 6K

- Replies

- 59

- Views

- 10K

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 3 (members: 0, guests: 3)