Twenty years ago, Pierre Cardin was looking for a house in Cannes, but he couldn't stand the prospect of the unoriginal villas that had multiplied all over the Côte d'Azur. He wanted the architectural equivalent of his avant-garde creations in fashion. Then, cutting across a point of land with a magnificent view of the Mediterranean, he happened upon a construction site. The project was being built by an architect named Antti Lovag for an industrialist with whom Lovag had become friends while building a previous house. The current one was most intriguing: It was to be a bubble-house, an unusual enterprise intended to demonstrate the possibility of short-circuiting traditional architecture in the name of original, contemporary design. Unfortunately, the industrialist with this brilliant vision died before the work was complete, which is where Cardin stepped in—overjoyed to acquire, almost ready-made, a residence that fit him like a glove.

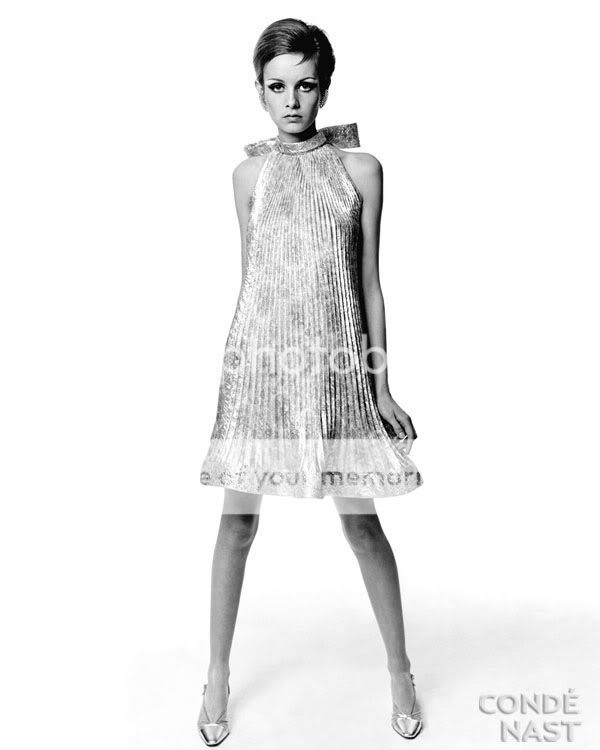

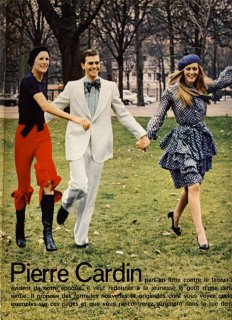

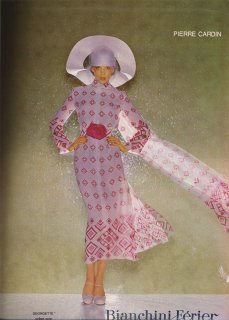

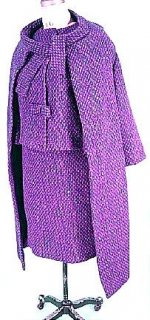

For what better habitation could one imagine for the genius behind the bubble dress, the trapeze coat, hat-sculptures, giant buttons, asymmetrical collars, and the chic-shock pairing of miniskirts and maxicoats? This promoter of the unusual in the realm of fashion—who got his start creating costumes and masks for Cocteau's La Belle et la Bête, was the first couturier to launch a ready-to-wear line, in 1959, staged the first fashion show in communist China, in 1979, and wasn't afraid to turn businessman, licensing his name to anything and everything and opening Maxim's restaurants worldwide—this agent provocateur had finally found his dream house.

He'd also found a kindred spirit. Lovag was born in Russia to a Russian Jewish father and a Finnish mother. The architect-to-be spent part of his childhood in Finland and Sweden, where he acquired a belief in the primacy of the functional. But because he also lived in Turkey as a child—and perhaps also because of his Russian influences—he associated functionality with aesthetics, and the curves and cupolas of Russian and Islamic architecture would reappear in his work. Later, studying naval architecture, he rediscovered curves in the hulls of boats. He eventually found a job with Jean Prouvé in Paris, then went to work for an architect in Sardinia. "He was a true artist," Lovag says of his Sardinian mentor. "First, he taught me what to avoid, technically. He also had a tremendous amount of taste and inventiveness in both architecture and decoration, which he saw as interconnected."

A heart attack inspired Lovag to reflect on life, and his new outlook of course influenced his architecture. "I discovered that I was mortal—meaning I discovered that I was free. I realized that building as if for eternity is an attack on time itself. Furthermore, it usually leads to an angular, aggressive organization of space. On the other hand, when one knows one's limits, all that is swept away. I began to think about improvised buildings, cobbled together on-site and adapted to a particular person's desires or idea of a house," he explains. "Instead of construction based on prefabricated panels, I began experimenting with frameworks that could be bent and changed and with techniques of concrete surfacing. That way, forms could move again." Architecture's first task, he came to believe, was to eliminate inhuman angularity.

Cardin, too, adores curves. "The circle is my symbol," he says. "The sphere represents the creation of the world and the mother's womb. Holes, cones, breasts—I've always used them in my designs." Hence his immediate understanding with Lovag. Part cave, part space station, simultaneously organic and manic, the house evokes the art of Niki de St. Phalle and Louise Bourgeois. Outside the doors and windows, which Lovag compares to eyes looking from different perspectives, several round swimming pools mirror the circle theme.

Everything Cardin selected to furnish the interior is curves: the walls, the beds, the bathtubs, a suite of phantasmagoric armchairs. And it all seems to float in curving spaces where color plays an important part. "The lighting is designed so colors change according to the time of day," Lovag says. "There's nothing more disheartening than white walls. They make you think you're in the hospital."

Speaking of hospitals, most people dismissed Cardin's Mediterranean retreat as a high-style lunatic asylum when Lovag completed construction in 1990. "Crazy House," they called it. Now it's considered a historic monument.

But it is amazing because it certainly looks as though it was made just for him! B)

But it is amazing because it certainly looks as though it was made just for him! B)