BerlinRocks

Active Member

- Joined

- Dec 19, 2005

- Messages

- 11,216

- Reaction score

- 14

If they were not there (Karl and Tom) it means they were NOT invited....

....

....

If they were not there (Karl and Tom) it means they were NOT invited....

....

Saint Laurent's Finale Shows Why He Is an Icon

A 15-minute ovation greeted Yves Saint Laurent onstage as he bowed out of fashion after 40 years, with Catherine Deneuve singing to him and an army of his models behind.

With his name up in lights outside the Pompidou art museum and a crowd of couture-clad women fighting to get through the crash barriers, Paris on Tuesday gave its fashion hero and the world's greatest living designer a magnificent send-off.

The worlds of politics and the arts melded in the front row as Bernadette Chirac, wife of the French president, and Danielle Mitterrand, widow of the former president, mingled with clients, celebrities and other designers to pay homage to the master.

By the time Jerry Hall — one of many famous model faces — sashayed down the runway in a white satin dress and snowy feather coat to "La Vie en Rose," the audience was drowning this 300-piece retrospective show in applause.

But even before the iconic outfits — from the first YSL tuxedo or see-through blouse from the 1960s to the parade of gorgeous 1970s Russian peasants — emotions were running high in the enormous forecourt, filled with rows of small gilt salon chairs.

"I feel good," said Pierre Berge as he greeted Francois Pinault, who bought the house of YSL. "Yves went when and how he wanted to, not being pushed or by ill health."

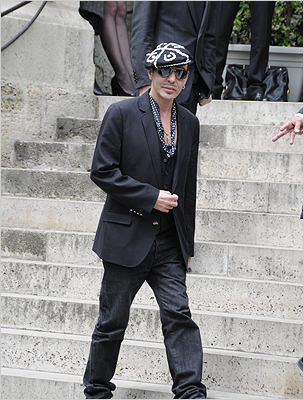

The only notable absentees were Tom Ford, Saint Laurent's successor for the YSL label, and Ford's partner at Gucci Group, Domenico de Sole.

One small figure, dressed in a black velvet suit with Saint Laurent's fetish red crystal heart at her neck, was already in tears: Lucienne Saint Laurent.

"I must feel good for my son, because it is what he wants — but my heart is breaking," said the designer's mother, who had spent Christmas with her son but was told of his decision only the night before the press conference where he announced it earlier this month.

The hourlong parade, watched by the public outside the museum on giant screens on a drizzly night, showed the extraordinary range and depth of Saint Laurent's work and his absolute integrity.

The show ran from his invention of the jacket-and-pants uniform of the modern woman through his astounding creations inspired by Picasso's harlequin paintings or the birds of George Braque. When the model Katouscha came out wearing a Braque bird dress in sweet blue and pink, Sonia Rykiel, one of many designers present, beat her hands in applause.

"Yves is irreplaceable," said Jean Paul Gaultier, another designer, while Alber Elbaz, a former designer at YSL, called it "a touching moment" and Yohji Yamamoto said, "I am shivering. He meant so much to me and my fashion generation."

Saint Laurent's show played with those emotions, changing register from the Beatles on the soundtrack for a line-up of Pop Art dresses to Mozart's "Marriage of Figaro" for swishing, romantic gowns.

"My heart is choked," said Hubert de Givenchy, who himself retired from fashion seven years ago. "All I wish for Yves is that he has the courage and the strength to support the coming empty years — and to turn his great talent to something else."

Other designers were lavish in their praise, with Vivienne Westwood, dressed in clashing plaids, saying that Saint Laurent had done more for women than any other designer, while Paul Smith recalled his visits to the early couture shows, when he was 28 and Saint Laurent's collection related to the Vietnam War.

Those feisty early days were shown as Claudia Schiffer marched out in a safari suit laced down the front and Naomi Campbell wore one of a group of African-inspired beaded dresses that rose dramatically from under the stage.

But the show was also an homage to the arts of Paris: the extraordinary embroideries of Francois Lesage, recreating jackets replicating the iris and sunflower paintings of Vincent Van Gogh or a Bacchanalian orgy of three dimensional grapes; the dresses made entirely of feathers by the plumier Andre Lemarie; the gilded body molds, covering the bosoms, by the Lalannes.

Front-row friends and clients shared their memories. Liliane de Rothschild described the first wedding dress Saint Laurent made (when still at Dior) for her sister's daughter, mother of the actress Helena Bonham Carter.

Paloma Picasso recalled how her flea-market purchase of a 1940s outfit, worn to a Paris dinner party, had inspired her friend Yves to create a 1940s collection in 1971. That came down the runway as a square-shouldered coat with appliqued Daliesque red lips, one smoking a cigarette, and as a turban and platform-sole shoes that turned this wartime-look collection into a scandal at the time.

Perhaps what stood out most on the runway was the color: mixes of old rose and hyacinth, orange, purple and asparagus green. But there was also black, used in different fabrics to create color, as in a dull veil of chiffon against luminous satin or bright jet beads.

The mark of Saint Laurent's genius is the fact that it was so hard to tell which were the 2002 models inserted in this retrospective. When a 2002 tuxedo was announced by Berge, the audience exploded with applause. It followed an original version with a white frilly blouse that could have been worn by any clients in an audience who left feeling that they will not see his like again.

June 5, 2008 – Fashion legend Yves Saint Laurent was laid to rest in Paris today. Among the mourners who gathered at the Église Saint-Roch, near the Louvre, were French President Nicolas Sarkozy and his wife, Carla Bruni-Sarkozy (in a black trouser suit, a tribute to a designer who was an early champion of the style); Pierre Bergé, Saint Laurent's longtime business partner; YSL muses Catherine Deneuve and Inès de la Fressange; and designers such as John Galliano, Valentino, Vivienne Westwood, and Kenzo. The real tribute to the great designer's influence, though, may have been the more than 1,000 people who gathered in the street outside the church to pay their last respects.

Yves Saint Laurent, couturier, died on June 1st, aged 71

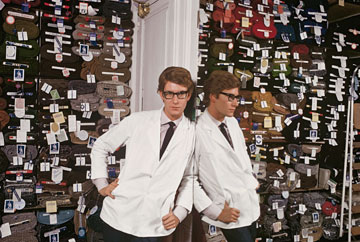

THE first intimation, apparently, was when three-year-old Yves told his mother that her shoes did not go with her dress. They were at home in Oran, a dull commercial town in French-ruled Algeria, where Yves's father sold insurance and ran a chain of cinemas, and Mrs Mathieu-Saint-Laurent cut an elegant figure in colonial society. Oran had once enjoyed some small renown as the westernmost outpost of the Ottoman empire, and was to gain more later as the setting for Albert Camus's “The Plague”. But after 1936 it had a genius in the making.

So, at any rate, the tribute-payers are saying. “Pure genius”, “the world's greatest fashion designer”, “the most important designer of the 20th century”: such superlatives have been lavished on Yves Saint Laurent (he wisely got rid of the Mathieu) for years, and perhaps they are not meant to be taken at face value. The fashion business is, after all, a part of the entertainment industry, where sycophancy, exaggeration and gushing insincerity are not unknown. Mr Saint Laurent fitted perfectly into it.

He was, for a start, quite literally a showman, a shy and stage-frightened one, but what shows he could put on! Dazzling girls strutted down the catwalk, wearing startling creations of gauze, or velvet, or feathers, or not much at all. He was a celebrity, whose circle included Lauren Bacall, Maria Callas, Rudolf Nureyev, Paloma Picasso, Gettys, Jaggers, Rothschilds and, from almost first to last, Catherine Deneuve. He was an artist, a delicate, attenuated figure who drew his inspiration from the pages of Marcel Proust, the paintings of Braque, Matisse, Picasso and van Gogh, and the counsels of his assistant, Loulou de la Falaise. And he was troubled: by drink, by drugs and by physical frailty. He teetered perpetually on the brink of emotional collapse and sometimes fell over it; his lover, Pierre Bergé, said he had been born with a nervous breakdown.

The great liberator

In 1961, when Mr Saint Laurent set up shop in Paris under his own name, most couturiers were not quite like this. But the times were propitious for something new. He had by then done a stint at the House of Dior, whose reputation he had restored with some dramatic designs and, in 1958, after the famous founder had died, an iconoclastic collection of his own. The summons to do military service, a ghastly mental dégringolade and dismissal from Dior then intervened, and might have cut short a great career had he not gone into partnership with Mr Bergé. As it was, a series of innovations followed, with Mr Saint Laurent responsible for the designs, Mr Bergé for the business, including the scents, scarves, unguents and over 100 other products marketed with a YSL label.

The dress designs now started flying off Mr Saint Laurent's drawing board, though increasingly often with the aid of helpers. Many were short-lived, this being fashion and fashion being, by definition, ephemeral (not for nothing does à la mode mean “with ice cream” in America). But two departures were to last. One was that haute couture, hitherto available only to the very rich or vicariously through magazines and newspapers, should be sold worldwide in ready-to-wear shops at a fraction of the posh price. The other was that women should be put into men's clothes—safari outfits, smoking jackets, trench coats and, most enduringly, trouser suits. Women, for some reason, saw this as liberation.

Mr Saint Laurent's young models looked pretty good in his designs, but they would have looked good in anything; older women in the same outfits sometimes seemed more like mutton dressed as ram. He did not confine himself to androgynous clothing, though: he also favoured diaphanous blouses worn without underwear, a fashion that has supposedly returned this year, though most busts still seem to be encased in polystyrene.

He was always imaginative, taking inspiration not just from artists like Mondrian but also from Africa and Russian ballet. He was also capable of creating the absurd, producing, for example, a dress with conical bosoms more likely to impale than to support. But his clothes, however outré, were usually redeemed by wonderful colours and exquisite tailoring. Above all, they were stylish, and the best have certainly stood the test of time.

That is no doubt because most were unusually wearable, even comfortable. At a reverential extravaganza in (and outside) the Pompidou Centre in Paris in 2002, soon after Mr Saint Laurent had announced his retirement, many of the guests wore a lovingly preserved YSL garment. The “anarchist”, as Mr Bergé recently called him, had by now become more conservative, seeing the merits of “timeless classics” and lamenting the banishment of “elegance and beauty” in fashion. He believed, he said, in “the silence of clothing”.

Yet perhaps he must take some of the blame for the new cacophony. The trouser suit prepared the way for the off-track track suit; and lesser designers, believing they share his flair and originality, now think they have a licence to make clothes that are merely idiotic. Perhaps it would have happened without him. In an industry largely devoid of any sense of the ridiculous, he was usually an exception. He believed in beauty, recognised it in women and, amid the meretricious, created his share of it.

PARIS — Two shopgirls in their uniform red jackets and black blouses stared down from the windows above the Elena Miro shop on the Rue du Faubourg St.-Honoré on Thursday, as the fashion world gathered below to mourn Yves Saint Laurent.

Elena Miro is across the narrow street, blocked by the police, from the St.-Roch Church, sometimes considered “the church of artists,” because it contains the graves of Corneille and the landscape architect André Le Nôtre. There, the world of French power and glitter held funeral services on Thursday for Mr. Saint Laurent, who was generally regarded, as the daily newspaper Le Figaro called him, the finest fashion designer of the last half of the 20th century.

He rarely if ever designed for the women who buy at Elena Miro, which sells clothes for what is gently termed full-figured women. But he was considered a liberator of women, making trousers both fashionable and acceptable, and it was largely the women of Paris who lined the streets behind the police to mourn Mr. Saint Laurent and who stood to watch the big screen that showed the funeral going on inside.

They clapped as Mr. Saint Laurent’s plain oak coffin entered the church, and again, 90 minutes later, when it left, this time covered with the flag of France.

“The most beautiful clothes that can dress a woman are the arms of the man she loves,” he once said. “But for those who haven’t had the good fortune of finding this happiness, I am there.”

He died Sunday, at 71, of a brain tumor, after an enormously creative and tumultuous life, which was also marked by psychological fragility and drug abuse.

For someone whose clothes could be lighthearted — dinner jackets for women and transparent blouses — the mood inside the church, lavishly decorated with greenery, jasmine and white lilies, was respectful and somber. But his colleagues and some of the famous women they dressed shared the sense in the streets that this was a life to be celebrated, and that he had brought glory to France, whose domination of fashion is considered long gone.

The president of France, Nicolas Sarkozy, was there, with his wife, Carla, a former model and singer. Like many of the women in the church, she wore black trousers, a gesture of respect and even homage to Mr. Saint Laurent, for whom she once modeled.

Catherine Deneuve, one of his most loyal friends and customers, carried a sheaf of green wheat into the church, then read a eulogy to him, in the form of a poem by Walt Whitman.

There was considerable head-turning, too, as famous designers and celebrities filed by, among them Sonia Rykiel, Jean-Paul Gaultier, John Galliano, Christian Lacroix, Vivienne Westwood, Valentino, Hubert de Givenchy, Kenzo Takada and Inès de la Fressange.

Other celebrities included the actress Jeanne Moreau; the model Laetitia Casta; Farah Pahlavi, the widow of the deposed shah of Iran; Bernard Arnault, the chairman of the luxury group of companies LVMH; and François and François-Henri Pinault, who own the brand name of Yves Saint Laurent.

Many of them lined up, eyes wet, for communion, but as much as the priest tried to capture the importance of Mr. Saint Laurent, it was his former companion and business partner, Pierre Bergé, who spoke most movingly.

The two men, who remained business associates and friends long after their romance ended, decided to create a civil union together in the days before Mr. Saint Laurent died, Mr. Bergé said. The French union, known as a “civil pact of solidarity,” carries mutual rights and responsibilities, but is short of a marriage.

“It’s going to be necessary to part now,” Mr. Bergé said, addressing his friend in the coffin. “I don’t know how to do it because I never would have left you. Have we ever left each other before? Even if I know that we will no longer share a surge of emotion before a painting or a work of art.”

Mr. Bergé’s voice broke. “But I also know that I will never forget what I owe you, and that one day I will join you under the Moroccan palms.”

Mr. Saint Laurent, born in Oran, Algeria, will be cremated and his ashes buried in a botanical garden he restored in Marrakesh, Morocco, near a home he and Mr. Bergé bought together.

Mr. Bergé said he would mark Mr. Saint Laurent’s grave with the words “French couturier.”

“French because you could have been nothing else,” he said. “French like a verse of Ronsard, a parterre of Le Nôtre, a page of Ravel, a painting of Matisse.”

Outside, as Mr. and Mrs. Sarkozy walked behind the flag-draped coffin, a military honor guard played, given Mr. Saint Laurent’s rank as a Grand Officer in the Legion of Honor, awarded to the dying man in December by Mr. Sarkozy.

But the incongruities abounded. Called to the army in September 1960 for 27 months of compulsory service during the Algerian war, despite running the house of Dior, Mr. Saint Laurent had a nervous breakdown three weeks later. He was put into the psychiatric ward of a hospital, where he was drugged and left alone in a room to be caressed and abused, he said in 2002.

“In two and a half months, I was so scared I only went once to the toilets,” he said. “At the end, I must have lost 35 kilos and I had disturbances in my brain.”

On Thursday, as the band played and official France paid homage, all that, too, was forgotten.

MANILA, Philippines—You have been wearing an “Yves Saint Laurent” —without you knowing it.

Of course, we don’t mean the brand. We mean the iconic styles Yves Saint Laurent has given fashion for nearly five decades, from the trouser suits to what you know as peasant dresses, and what your daughter now calls “boho chic.”

Fashion is a never-ending evolution—and cycle—and Saint Laurent—the genius who embraced pain of creation more than he did life—had always been at the root of this evolution.

He greatly influenced the foremost Filipino fashion designers. During his ascendance in the ’70s, Filipino fashion designers were also at their most productive, competitive and versatile stage. It was the golden era of Philippine fashion that gave rise to today’s iconic figures. From the time I started interviewing and covering the likes of Auggie Cordero, I heard no fashion titan’s name dropped more often than Yves Saint Laurent.

Saint Laurent was the reference for the neat tailoring and sleek silhouette of Cordero and Inno Sotto. Jeannie Goulbourn’s corporate woman look in the heyday of Philippine ready-to-wear was inspired by a Saint Laurent. Cesar Gaupo’s bold color play heeded Saint Laurent’s example.

It’s been said that no designer has affected hemline and waistline as much as YSL did.

That’s no exaggeration. Unlike Dior and Chanel, YSL was there for a much longer period—five decades—producing collections four times a year, particularly when he also started his RTW Rive Gauche line. This was a challenge to human creativity that took its toll on the man’s physical and psychic health. As his longtime business partner and companion Pierre Berge said, YSL “was born with a nervous breakdown.”

Christian Lacroix explained how YSL was in a league all his own: “There have been other great designers in this century, but none with the same range as Saint Laurent. Chanel, Schiaparelli, Balenciaga and Dior all did extraordinary things. But they worked within a particular style. Yves Saint Laurent is much more versatile, like a combination of all of them. ”

What exactly were the forms—and substance—of fashion Philippine designers and women in general owed to Saint Laurent?

To start with, the trouser suit of the ’70s was an innovation by Saint Laurent at a time when it wasn’t considered feminine for women to be in pants for serious day and evening occasions.

The trapeze dress is another. In his first collection after the death of Dior, the young YSL introduced a non-constricting silhouette devoid of paddings and linings associated with the older Dior.

In the ’60s, he caught the wave of pop art and Op art, and designed the Mondrian shift which bore the geometric figures of the artist Mondrian. The dress was lauded by critics—it allowed room for the woman’s curves while appearing as flat as a painting’s surface.

In the mid-’70s, Saint Laurent introduced his “Ballet Russes” collection. He was inspired by Diaghilev’s “Ballet Russes”—billowing skirts, shawls, harem pants in jewel colors. He introduced fantasy dressing of Saint Laurent.

Tuxedo dressing sprang from Saint Laurent’s “smoking” jacket of 1967, consisting of shirt, kerchief out of the breast pocket, trouser suit. Saint Laurent used traditional men tailoring in a new way for women. He paved the way for Armani in that sense.

He also introduced the safari jackets for men and women—and the designer denim.

From the ’70s to the early 21st century, these looks made their way to Philippine fashions. As Women’s Wear Daily repeatedly wrote: Saint Laurent was the “sense of color, the artistry of cut.”

Fashion’s legendary journalist John Fairchild, the founder of WWD, said “Dior, Chanel, Saint Laurent”—that about summed up high fashion.

Thanks to his partnership with Berge, who was known for his business acumen, Saint Laurent pioneered not only RTW, but also the licensing of the fragrance and beauty business.

Chanel saw life as an adventure. Dior had a zest for life. YSL had the angst of life. YSL—painfully shy and reclusive—seemed to have embraced the struggle that came with his genius.

In an interview this week on CNN, Berge said YSL seemed to have lost his drive after he retired in 2001. Even if he did, it actually didn’t matter anymore. Yves Saint Laurent had already given enough to the world.

France Says Farewell

By Robert Murphy

PARIS — Hundreds of onlookers thronged behind barriers around the Eglise Saint-Roch here Thursday as the world of fashion bid adieu to Yves Saint Laurent.

French President Nicolas Sarkozy, accompanied by First Lady Carla Bruni, decorated Saint Laurent's oak coffin with the French flag and gave Saint Laurent military honors in the late designer's capacity as a grand officer in the French Legion of Honor.

When Saint Laurent's remains arrived at the 17th-century church on the Rue Saint-Honoré on the Right Bank, applause erupted from the crowd that had come to pay their respects to the celebrated couturier, who retired in 2002. Saint Laurent died of brain cancer Sunday at age 71.

The memorial mass is likely to be remembered as one of the most important and biggest French fashion funerals since the death of Christian Dior in 1957. After the mass, Saint Laurent was cremated and his ashes are to be flown to Morocco, where they will be placed in an urn in the Majorelle Gardens.

People began to arrive outside the church in the morning to stake out a spot behind the police cordon from which to watch the mass. A giant-screen television, first broadcasting YSL fashion shows (including the designer's farewell in 2002), was erected outside the church for the public, who snaked around the block. Inside, the church, Paris' parish for artists, was redolent with lilies and jasmine, while the outside was ringed with bouquets of white roses.

The mass started at 3:30 p.m., but the more than 800 guests began to trickle in as early as 2 p.m. A visibly emotional Catherine Deneuve arrived cradling a bouquet of wheat. "Saint Laurent was pure elegance," she said.

Other notables included Valentino, Marc Jacobs, Christian Lacroix, John Galliano, Alber Elbaz, Sonia Rykiel, Jean Paul Gaultier, Stefano Pilati, Kenzo Takada, Hubert de Givenchy, Vivienne Westwood and Ricardo Tisci. Giorgio Armani and Hedi Slimane were among the designers expected, but they were ultimately unable to attend.

LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton chairman Bernard Arnault, PPR owner François Pinault, Bernadette Chirac, Paris mayor Bertrand Delanoe, Robert Polet, Valerie Hermann, Sidney Toledano, Jacqueline de Ribes, Philippine de Rothschild, Farah Diba, Bethy Lagardère, French writer Bernard-Henri Lévy and his wife, Arielle Dombasle, Ines de la Fressange, Laetitia Casta and Claudia Schiffer also climbed the stone steps to the church.

The mass was a solemn affair, punctuated by moving music, including live renditions of Vivaldi's "Stabat Mater" and Mozart's "Requiem," and a recording of Bellini's "Casta Diva" by Maria Callas.

The coffin, greeted by applause outside, was borne into the church in utter silence. Pierre Bergé, Saint Laurent's companion and business partner of 50 years; the late designer's mother, Lucienne Mathieu Saint Laurent, and his sisters Brigitte and Michele; other immediate family, and members of his inner circle, including Betty Catroux, followed.

Once the coffin had been laid on the altar, a string quartet played the andante moderato from Johannes Brahms' "String Quartet no. 1 in B flat major," followed by a crackled recording from the Sixties of Saint Laurent briskly answering the Proust Questionnaire, the series of questions asked of famous people in the back pages of Vanity Fair issues since 1993.

Father Roland Letteron presided over the service, during which he praised Saint Laurent's ability to transform his personal suffering into creative genius. Letteron made a case for Saint Laurent being called an artist and not merely an artisan. "We buried another artisan in this church — a gardener," said Letteron, referring to 17th-century landscape architect André Le Nôtre. He added Saint Laurent had become an artist in the noble approach he took to fashion.

Fighting back tears, Deneuve, a big YSL heart pendant hanging from her neck, read a poem by Walt Whitman.

Bergé followed Deneuve's homage, recalling in a 10-minute tribute of his own how he met Saint Laurent a half century ago and the two men decided to combine their destinies into what would become one of fashion's most historic partnerships.

"How could I have imagined that 50 years later I would be here addressing you for the last time?" said Bergé in an emotional tone.

"It is to you that I'm talking," he continued. "You who can't answer me."

Bergé's remembrance of his relationship with Saint Laurent was eloquent, touching and intensely personal, provoking tears from many guests. "I remember the first collection you did under your own name. How quickly the years have passed."

He continued, "I want to tell you the qualities I most loved in you: honesty, rigor and perfectionism.

"Artists are made to create; it's their only raison d'être. You lived to create. You belonged to the grand family of the sensitive that are the salt of the earth. I have to leave you. I don't know how to do it because I'll never leave you....One day I'll join you under the Moroccan palm trees. I want to tell you of my admiration, profound respect and love."

At the end of his speech, the crowd outside the church could be heard applauding. Once Bergé, his head hanging low, passed Saint Laurent's coffin and returned to his seat, Jacques Brel's "La Chanson des Vieux Amants," or the "Song of Old Lovers," was played.

Saint Laurent's coffin then was borne out of the church and set on a plinth on the street before a row of uniformed military officers hoisting bayonets. A hush fell over the crowd as the Sarkozys exited with Bergé, trailed by other VIPs.

The group stood on the steps for several moments for photographs, before the president left with his motorcade, the crowd chanting "Nicolas, Nicolas." Bergé departed in the hearse with Saint Laurent's coffin, the crowd erupting in fresh applause.

Before and after the service, attendees expressed grief, shared memories and trumpeted Saint Laurent's indelible legacy.

"We were close friends back in the days when he, Karl [Lagerfeld] and I studied in Paris and would meet at night at the Café de Flore and hang out," recalled Roman couturier Valentino. "I was 22, Yves 18 and Karl more or less my same age. We were young, free-spirited and had a passion for fashion, for life.

"Yves was a great colleague," he continued. "I admire his faith to a precise style that has never passed, his interminable fantasy and the respect for women and beauty. He has left an immense heritage by which all young designers should be inspired. Fashion isn't losing Yves. His work stays in his archives, in the work of who is inspired by him and in our memories."

Pilati, creative director of Yves Saint Laurent since 2004, couldn't agree more: "Mr. Saint Laurent influenced everyone, including every designer that came after him because, in my estimation, his greatness surpassed that of any of his peers. Now that I am a designer, and designing for the house that he founded, I can acknowledge this influence and I can say with confidence that he will continue to inspire me.

"I live a YSL moment every day of my professional life and it's almost impossible to imagine it any differently," Pilati continued. "The success, the recognition, the response to my daily work at the house is what helps me to 'respect' the legacy instead of merely 'coping' with it. It is a pleasure and it is a passion, and as such I look ahead vigilantly every day, which is itself a gift Mr. Saint Laurent gave to the world of fashion."

"He was one of the most elegant, well-mannered, cultured and gentle people of this world," said Schiffer, her eyes shielded by dark glasses. "I remember meeting him for the first time at his atelier in Paris, I was trying on the tuxedo finished off with YSL red lipstick. It was a very intimate and warm welcome. I was terribly shy and quiet. He had this air of shyness about him too, which made me feel immediately comfortable and close to him. He changed the face of fashion and made a mark on the world that can never be forgotten."

Marisa Berenson said Saint Laurent's passing represented the "closing of a chapter for us all. Those were such important days of our youth. He had such elegance of heart and mind."

"We were really good friends," noted French actor Pascal Greggory. "We went on holiday together often, to Morocco, to Russia. I have a thousand memories of him. It's a shock."

Westwood said she met the couturier several times backstage. "He was always so pleased when you liked what he did. He was extraordinary," she said.

"He was my idol when I started out," said Takada. "He expressed the beauty of women. I did get to know him and would sometimes have dinner with him in Tangier. He was very shy, and so am I — especially in front of a giant like Yves Saint Laurent — so it was sometimes a little [awkward]. There were other [fashion] greats, such as Chanel, but he marked the century."

Designer Jean-Paul Knott, who worked for Saint Laurent for a dozen years, straight out of school, had an inauspicious beginning.

"The first time I met him, I went into the studio and I was panicking and trembling and Moujik, his dog, the second Moujik I think, jumped up and bit me in the leg. And Mr. Saint Laurent came to get him, and apologized. It was my first week," Knott said. "He taught me to look, and to have respect for people and for things: To such an extent that when you looked at something with him, you saw it differently. He was very reserved, he showed very little what he was thinking, but he had this enormous energy, with an enormous force. He was never happy. He was a perfectionist."

But it was perhaps Edmonde Charles-Roux, writer and former chief editor of French Vogue, who captured the mood of France. "We are all very, very sad, even the taxi drivers are sad," Charles-Roux said. "I took a taxi [the other day] and we passed in front of the Madeleine church and the driver exploded and I asked what's wrong. And he said, 'When you think of that beautiful church in the center of Paris, and then you think of Saint-Roch. Well, it's a scandal. We had a genius and the church is not big enough.' The people on the street are sad."

exactly..If they were not there (Karl and Tom) it means they were NOT invited....

....

....

....