You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Maggie Cheung

- Thread starter Estella*

- Start date

whirlygirl said:She looks amazing in the editorial on pg.1. That Balenciaga collection suits her.

yeah...I

her look...

her look...I gotta leave and next time, I will find more pics of her...

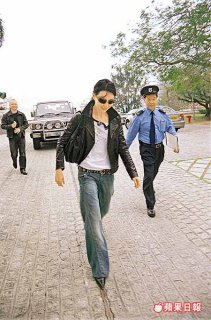

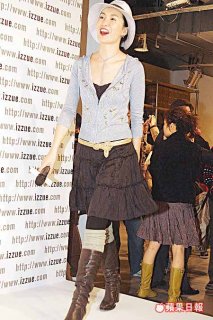

she has such simple while graceful style...easygoing while special...she said she liked to design clothes and actually she once had been the director disgner of a HK brand www.izzue.com for lone time and she left this brand around july or august of 2005. she likes to do her own makeup, hair, and dressing. She even maked up herslef in the movies and cut her hair herself. Wow...she could save a lot $ in this way...LoL, kiding, though....

Last edited by a moderator:

kimair said:i merged this thread with the existing one on maggie...

please do a search before starting a new thread

I See...while honestly , I searched Maggie Cheung, while no result...so I thought...

And thanx for merging, so we can have a big thread of her...

juliadawn said::-)I like her

I must typed in the wrong letters when I did the search...

I must typed in the wrong letters when I did the search...sorry...

bluedolphin

Active Member

- Joined

- Jan 13, 2006

- Messages

- 4,733

- Reaction score

- 4

http://www.nytimes.com/pages/magazine/index.html

(摄影:Jean-Baptiste Mondino)

Why Isn’t Maggie Cheung a Hollywood Star?

By SUSAN DOMINUS

Published: November 14, 2004

Having spent the greater part of the day indoors, giving back-to-back interviews about her latest film, “Clean,“ at the Toronto International Film Festival, the actress Maggie Cheung exited the InterContinental Hotel to meet a spectacularly sunny early fall afternoon. As she strode through the doorway, she ran into a friend from a film shoot, and Cheung, possibly the most famous woman in China, chatted gaily in Cantonese with her colleague, casually standing on the sidewalk as if no one would notice. Close to a minute ticked by before one of the photographers lingering outside the hotel spotted her, possibly because Cheung was wearing Gucci sunglasses so large they were more like small, reflective plates perched on her fine face. Once one photographer was up and snapping there were suddenly 2, then 4, then 16, until a swirling cloud of microphones and flashbulbs formed around her, gathering as if by some centripetal force, sucking in ever growing numbers of fans and quote seekers and photo snappers, most of them Asian cineastes in town for the festival.

Cheung, accustomed to such crowds, is also accustomed to having people materialize to help her through them, and a young Canadian woman working in public affairs for the festival took Cheung’s arm uncertainly. Someone hailed a taxi, and Cheung made her way toward it, laughing lightly as she turned to wave goodbye to her friend. She didn’t look as if she’d just escaped a claustrophobic clutch; she looked amused and a bit embarrassed, as if she’d just dashed through a funny little rain shower without an umbrella.

The barometer of public reception, for Cheung, is always uncertain in North America. In Hong Kong, where she has been a star since placing first runner-up in the 1983 Miss Hong Kong pageant at age 18, Cheung, now 40, once holed up in her apartment for three straight weeks to avoid the throng of photographers and reporters outside. In New York and Los Angeles, on the other hand, she is rarely approached even for an autograph, unless it’s from an Asian tourist lucky enough to catch her on the street. She is also barely a recognizable face in Canada, which may explain why she allowed herself the luxury of some spontaneous streetside conversation, forgetting that a film festival subverts the normal laws governing her fame in this part of the world.

Cheung has been a fixture of Asian superstardom for 21 years and has won more acting awards in China than any other woman. She started out as Jackie Chan’s long-suffering, slapsticky girlfriend, May, in the goofy action-oriented “Police Story“ movies. (Chan said that when he first saw Cheung on Hong Kong TV, she struck him as someone who “wouldn’t mind me kicking her down a flight of stairs.“) Eventually tiring, as much physically as creatively, of action films, by the late 80’s she had started working with the dreamy, painterly filmmaker Wong Kar-wai, trading her role as a plucky comic for more nuanced parts in films like “As Tears Go By“ and “In the Mood for Love“ -- women with a noirish unattainability or ingenues shedding their innocence. In the mid 90’s, she crossed over to select Western audiences for the first time, working with the French director Olivier Assayas, whom she would eventually marry and who directed her recently in “Clean,“ the film for which she won the best actress award at Cannes. For Cheung’s Asian audiences, it’s as if they’ve watched her morph over the years from Audrey Hepburn to Greta Garbo.

So why is it that American audiences know Cheung only vaguely, if at all, as the woman who fended off a torrent of arrows in the Chinese film “Hero,“ which was a sleeper success in the United States this summer? It’s somewhat mystifying that one of Asia’s finest actresses is virtually unknown to Hollywood audiences, as if celebrity were the one export too fragile to make the 7,000-mile trip across the Pacific. Cheung’s English, though accented, is fluent; her beauty, universal; her talent, unarguable -- the imprimatur of Cannes confirmed the cross-cultural appeal her Chinese fans have appreciated for decades. To wonder why Cheung isn’t a Hollywood star is to wonder a bigger question: why hasn’t any contemporary Asian actress become a major Hollywood star?

sitting comfortably in the lobby of the boutique hotel where she was staying in Toronto, Cheung, still wearing her sunglasses, didn’t initially seem to find the question particularly compelling. “I haven’t really bothered to explore it, but maybe it’s normal,“ she said. “If you were making a Hong Kong film, what would you expect to do with Robert De Niro? He can play an American living in Hong Kong, but after that. . . . “ She lighted a cigarette, then thought for a moment. “Then again, now there are so many Asians living abroad, it shouldn’t really make a difference.“

(摄影:Jean-Baptiste Mondino)

Why Isn’t Maggie Cheung a Hollywood Star?

By SUSAN DOMINUS

Published: November 14, 2004

Having spent the greater part of the day indoors, giving back-to-back interviews about her latest film, “Clean,“ at the Toronto International Film Festival, the actress Maggie Cheung exited the InterContinental Hotel to meet a spectacularly sunny early fall afternoon. As she strode through the doorway, she ran into a friend from a film shoot, and Cheung, possibly the most famous woman in China, chatted gaily in Cantonese with her colleague, casually standing on the sidewalk as if no one would notice. Close to a minute ticked by before one of the photographers lingering outside the hotel spotted her, possibly because Cheung was wearing Gucci sunglasses so large they were more like small, reflective plates perched on her fine face. Once one photographer was up and snapping there were suddenly 2, then 4, then 16, until a swirling cloud of microphones and flashbulbs formed around her, gathering as if by some centripetal force, sucking in ever growing numbers of fans and quote seekers and photo snappers, most of them Asian cineastes in town for the festival.

Cheung, accustomed to such crowds, is also accustomed to having people materialize to help her through them, and a young Canadian woman working in public affairs for the festival took Cheung’s arm uncertainly. Someone hailed a taxi, and Cheung made her way toward it, laughing lightly as she turned to wave goodbye to her friend. She didn’t look as if she’d just escaped a claustrophobic clutch; she looked amused and a bit embarrassed, as if she’d just dashed through a funny little rain shower without an umbrella.

The barometer of public reception, for Cheung, is always uncertain in North America. In Hong Kong, where she has been a star since placing first runner-up in the 1983 Miss Hong Kong pageant at age 18, Cheung, now 40, once holed up in her apartment for three straight weeks to avoid the throng of photographers and reporters outside. In New York and Los Angeles, on the other hand, she is rarely approached even for an autograph, unless it’s from an Asian tourist lucky enough to catch her on the street. She is also barely a recognizable face in Canada, which may explain why she allowed herself the luxury of some spontaneous streetside conversation, forgetting that a film festival subverts the normal laws governing her fame in this part of the world.

Cheung has been a fixture of Asian superstardom for 21 years and has won more acting awards in China than any other woman. She started out as Jackie Chan’s long-suffering, slapsticky girlfriend, May, in the goofy action-oriented “Police Story“ movies. (Chan said that when he first saw Cheung on Hong Kong TV, she struck him as someone who “wouldn’t mind me kicking her down a flight of stairs.“) Eventually tiring, as much physically as creatively, of action films, by the late 80’s she had started working with the dreamy, painterly filmmaker Wong Kar-wai, trading her role as a plucky comic for more nuanced parts in films like “As Tears Go By“ and “In the Mood for Love“ -- women with a noirish unattainability or ingenues shedding their innocence. In the mid 90’s, she crossed over to select Western audiences for the first time, working with the French director Olivier Assayas, whom she would eventually marry and who directed her recently in “Clean,“ the film for which she won the best actress award at Cannes. For Cheung’s Asian audiences, it’s as if they’ve watched her morph over the years from Audrey Hepburn to Greta Garbo.

So why is it that American audiences know Cheung only vaguely, if at all, as the woman who fended off a torrent of arrows in the Chinese film “Hero,“ which was a sleeper success in the United States this summer? It’s somewhat mystifying that one of Asia’s finest actresses is virtually unknown to Hollywood audiences, as if celebrity were the one export too fragile to make the 7,000-mile trip across the Pacific. Cheung’s English, though accented, is fluent; her beauty, universal; her talent, unarguable -- the imprimatur of Cannes confirmed the cross-cultural appeal her Chinese fans have appreciated for decades. To wonder why Cheung isn’t a Hollywood star is to wonder a bigger question: why hasn’t any contemporary Asian actress become a major Hollywood star?

sitting comfortably in the lobby of the boutique hotel where she was staying in Toronto, Cheung, still wearing her sunglasses, didn’t initially seem to find the question particularly compelling. “I haven’t really bothered to explore it, but maybe it’s normal,“ she said. “If you were making a Hong Kong film, what would you expect to do with Robert De Niro? He can play an American living in Hong Kong, but after that. . . . “ She lighted a cigarette, then thought for a moment. “Then again, now there are so many Asians living abroad, it shouldn’t really make a difference.“

bluedolphin

Active Member

- Joined

- Jan 13, 2006

- Messages

- 4,733

- Reaction score

- 4

In “Clean,“ set mostly in Paris, Cheung plays a drug addict who is trying to recover so she can get her son back from the parents of the boy’s father, who died of a drug overdose. The character, which Assayas, now her ex-husband, wrote specifically for Cheung, happens to be Chinese, but that’s a minor aspect of her character, not the pivotal point of the plot: it’s not a film about immigration or interracial relationships or cultural misunderstanding. In France, the film was widely distributed and hit No. 2 at the box office in Paris. Cheung’s image appeared on the cover of every major French magazine, from Le Figaro’s weekly supplement to the downtown Les Inrockuptibles. “Ten years ago, I think audiences might have thought, What do I care about this Chinese woman?“ Cheung said. “In Europe, we’re about halfway there. But I think maybe American audiences still think that.“

Although she answered my questions about “Clean,“ Cheung started out by deftly putting off all other queries, instead posing a rapid-fire series of girlish inquiries about her interviewer (marital status, job satisfaction, sibling rapport), behavior that’s unusual in any interview subject, much less a celebrity. At first, it seemed a defensive ploy, but eventually she fell into an unguarded conversation about the dumping of men (“but let’s not call it dumping“), Chinese astrology, her thoughts on having kids (not ready but unconcerned), her qualms about her resistance to marriage (temporarily single at 35 was one thing, she said, but alone at 45 -- “I think, well, that wouldn’t be very nice“). Raised in England, Cheung has the curiosity of a royal who has only recently been let out of the castle; the freedom of her relative anonymity in the West has still not lost its freshness.

At one point, a suited man from the hotel came over and politely apologized that he had to ask Cheung to put out her cigarette, a request that appeared to cause him some anguish. Cheung smiled sweetly at him, her uptilted face a vision of feminine charm, and asked if, Oh, just this once, she might be able to, since no one else was around. His face turned bright red, and it looked as if it might kill him to insist, but insist he did, at which point Cheung sweetly put it out. Forthright with women, she can’t help being aware of the effect she has on men.

Assayas, a boyish 49-year-old well known in France for his cerebral films, says he was struck by Cheung’s charisma the first time he saw her in person. “The first time I met her was on a jury at the Venice Film Festival,“ he said when I met with him at a cafe near his home in Paris. “We were introduced, and right away I saw in her something I had never seen in another actress. In retrospect, I don’t know if it was love at first sight or something more serious.“ He paused, distracted by what he’d said. “I guess it doesn’t get much more serious than love at first sight,“ he mused, then laughed at himself and continued. “I thought she had something that is fascinating, something I associate more with stars of the past -- she projected something entirely striking but also incredibly modern, like an up-to-date version of an old-fashioned film star. I realized I’d never once made movies with movie stars. I’d made movies with actresses.“ He cast Cheung to play a version of herself in the 1996 film “Irma Vep,“ an independent movie that riffed off the French classic “Les Vampires.“ The two fell in love and married in 1998, then grew apart and separated two years later.

On one of the last nights of the Toronto festival, Assayas joined Cheung and several other cast members from “Clean“ at a restaurant for dinner. Everyone sat a bit awkwardly alongside a tall table, and the topic eventually turned to the early days of Assayas and Cheung’s work together. Because he was drawn to her by her star quality, Assayas said, he was surprised to find in Cheung a performer whose charisma was completely uncoupled from the Western notion of celebrity, which holds that great performances demand indulgence and coddling. To the contrary, there’s a diligence -- almost a dutifulness -- common to Cheung’s circle of Hong Kong performers, most of whom put up with the industry’s grueling production schedules. Cheung has raced her way through some 75 films, making as many as 11 in one year during the height of the Hong Kong film industry in the late 80’s. “You sleep in cars, you sleep on the set, anywhere you can,“ she said. Working on one of the “Police Story“ films with Jackie Chan, she had to run through a stack of bed frames, several of which collapsed on her head, sending her to the hospital for 17 stitches.

That evening, Cheung, who wore her sunglasses even in the dark bar, was dressed, as usual, in black, her hair pulled off her face in a ponytail, tall boots adding height to her already long-limbed frame. As she headed out of the bar, a little on the early side because of her jet lag, the American director Harmony Korine, in town for the festival, was heading in, and he made a beeline for the actress, his head bobbing at about sternum height on Cheung. “Ms. Cheung, I just wanted to tell you how much I admire your work,“ he said, and she smiled graciously, the very picture of cinematic royalty, before heading out onto a Toronto street where no one took note of who she was.

Although she answered my questions about “Clean,“ Cheung started out by deftly putting off all other queries, instead posing a rapid-fire series of girlish inquiries about her interviewer (marital status, job satisfaction, sibling rapport), behavior that’s unusual in any interview subject, much less a celebrity. At first, it seemed a defensive ploy, but eventually she fell into an unguarded conversation about the dumping of men (“but let’s not call it dumping“), Chinese astrology, her thoughts on having kids (not ready but unconcerned), her qualms about her resistance to marriage (temporarily single at 35 was one thing, she said, but alone at 45 -- “I think, well, that wouldn’t be very nice“). Raised in England, Cheung has the curiosity of a royal who has only recently been let out of the castle; the freedom of her relative anonymity in the West has still not lost its freshness.

At one point, a suited man from the hotel came over and politely apologized that he had to ask Cheung to put out her cigarette, a request that appeared to cause him some anguish. Cheung smiled sweetly at him, her uptilted face a vision of feminine charm, and asked if, Oh, just this once, she might be able to, since no one else was around. His face turned bright red, and it looked as if it might kill him to insist, but insist he did, at which point Cheung sweetly put it out. Forthright with women, she can’t help being aware of the effect she has on men.

Assayas, a boyish 49-year-old well known in France for his cerebral films, says he was struck by Cheung’s charisma the first time he saw her in person. “The first time I met her was on a jury at the Venice Film Festival,“ he said when I met with him at a cafe near his home in Paris. “We were introduced, and right away I saw in her something I had never seen in another actress. In retrospect, I don’t know if it was love at first sight or something more serious.“ He paused, distracted by what he’d said. “I guess it doesn’t get much more serious than love at first sight,“ he mused, then laughed at himself and continued. “I thought she had something that is fascinating, something I associate more with stars of the past -- she projected something entirely striking but also incredibly modern, like an up-to-date version of an old-fashioned film star. I realized I’d never once made movies with movie stars. I’d made movies with actresses.“ He cast Cheung to play a version of herself in the 1996 film “Irma Vep,“ an independent movie that riffed off the French classic “Les Vampires.“ The two fell in love and married in 1998, then grew apart and separated two years later.

On one of the last nights of the Toronto festival, Assayas joined Cheung and several other cast members from “Clean“ at a restaurant for dinner. Everyone sat a bit awkwardly alongside a tall table, and the topic eventually turned to the early days of Assayas and Cheung’s work together. Because he was drawn to her by her star quality, Assayas said, he was surprised to find in Cheung a performer whose charisma was completely uncoupled from the Western notion of celebrity, which holds that great performances demand indulgence and coddling. To the contrary, there’s a diligence -- almost a dutifulness -- common to Cheung’s circle of Hong Kong performers, most of whom put up with the industry’s grueling production schedules. Cheung has raced her way through some 75 films, making as many as 11 in one year during the height of the Hong Kong film industry in the late 80’s. “You sleep in cars, you sleep on the set, anywhere you can,“ she said. Working on one of the “Police Story“ films with Jackie Chan, she had to run through a stack of bed frames, several of which collapsed on her head, sending her to the hospital for 17 stitches.

That evening, Cheung, who wore her sunglasses even in the dark bar, was dressed, as usual, in black, her hair pulled off her face in a ponytail, tall boots adding height to her already long-limbed frame. As she headed out of the bar, a little on the early side because of her jet lag, the American director Harmony Korine, in town for the festival, was heading in, and he made a beeline for the actress, his head bobbing at about sternum height on Cheung. “Ms. Cheung, I just wanted to tell you how much I admire your work,“ he said, and she smiled graciously, the very picture of cinematic royalty, before heading out onto a Toronto street where no one took note of who she was.

bluedolphin

Active Member

- Joined

- Jan 13, 2006

- Messages

- 4,733

- Reaction score

- 4

The claim that no Asian actresses are making it big in Hollywood inevitably invites counterexamples: Lucy Liu, a star of “Charlie’s Angels,“ for one, or Cheung’s friend Michelle Yeoh, the former Bond girl. There’s no denying that these women are stars, but they’re stars of a specific sort: action heroes, variations of the old Asian warrior legends, exotic in both provenance and look. Penelope Cruz can play the romantic love interest opposite Tom Cruise, her accent nothing more than another adorable accouterment; Halle Berry, for better or worse, can get a film like “Catwoman“ green-lighted. It’s nearly impossible, however, to name a studio film in which an Asian-American actress plays the leading role, or the love interest, or even the love interest’s best friend, outside of specifically Chinese films like “The Joy Luck Club.“

Part of this disparity can be attributed to simple demographics: African-Americans represent 13 percent of the American population, Latino-Americans 14 percent, while Asians account for about 4 percent. But filmmakers don’t even represent demographics faithfully, argues Jeff Yang, the author of “Once Upon a Time in China,“ a book about Chinese cinema. “Even in a movie set in the greater Bay Area,“ he says, “where one out of three people is Asian-American, if you just look at the background scenes, the bystanders, there are almost no Asians at all. That’s not just politically incorrect -- it’s fundamentally, demographically, incorrect.“

Janet Yang (no relation to Jeff), who produced “The People Vs. Larry Flynt“ and “The Joy Luck Club,“ contends that geography and history place Asian actresses too far outside the range of the girl next door, practically a prerequisite for female superstardom in this country. “Asia has been perceived as the enemy for many years,“ she adds. “Look at all the past major wars -- World War II, Korea, then Vietnam. There’s this crazy, deep-rooted bias.“ At the time she produced “The Joy Luck Club“ in 1993, Yang thought the film was a breakthrough; now, she says, studios are even less likely to finance such a film, given the absence of a name-brand, non-Asian star. Richard Hicks, the president of the Casting Society of America, says he proposes Cheung to directors with some regularity: half the time, he says, logistics get in the way -- “can we get her here by Thursday?“ -- but just as often his clients aren’t interested in casting an Asian.

Cheung, for her part, has never been driven to disprove American audiences’ stereotypes of Asian performers. To the contrary, she hasn’t made much of an effort to break into Hollywood. She has never come to Los Angeles just to make the rounds and rarely makes herself available for auditions. Given the scarcity of roles she’d like to play, it has hardly been worth it to her to pursue Hollywood success, she said; her current schedule is demanding enough. When I met with her in Toronto, Cheung had made the 17-hour trip from Hong Kong to Canada for just four days and was quickly heading back for some professional obligations: a promised appearance at the opening of a store in Shanghai for Louis Vuitton, and then a couple of days of shooting for some mobile-phone ads and commercials for the Hong Kong audience.

Cheung’s face is everywhere in Hong Kong. Head to the pharmacy, and she smiles at you from an Oil of Olay promotional ad behind the counter. Walk by the newsstand, and she’s on the cover of Chinese Elle and on the billboards at the bus stop. An ad campaign she did for Ericsson hand-held phones in the late 90’s was so successful it was cited as a case study in the Harvard Business Review. An entire row of DVD’s is devoted to her at the massive HMV on the way to Victoria Park. Having significantly reduced the brutal pace of her filmmaking, Cheung continues to take on numerous promotions, figuring that it’s easier to make money in a few days of empty work than in a few months of another action film.

In September, when I visited Cheung in Hong Kong, she had just returned from the Vuitton party in Shanghai -- a disaster, she said, with photographers popping out of nowhere at the arrival of her current boyfriend, Guillaume Brochard, a Frenchman with a jewelry business. She enjoyed only a few days of rest before the shoots for the mobile-phone ads. Out late the night before, she looked tired but still a good 10 years younger than her age. “They don’t know I was out last night,“ she whispered in English, as the mobile-phone reps scrambled around, trying to find appropriate pieces of wardrobe, while a makeup artist tended to her.

Cheung, who helped design her own theatrical makeup in “Hero,“ occasionally took one brush or another from the makeup artist to do the work herself. Although she clearly knows what she’s doing -- she teased her eyelashes out, transforming herself from the coolly disheveled Emily of “Clean“ to the elegant beauty of “In the Mood For Love“ -- makeup is her least favorite part of her job. During the shooting of “In the Mood,“ for 15 months she went to bed at 8 a.m., was picked up at noon to arrive on set by 1 p.m. for hair and makeup, then shot until late in the night, a schedule that it’s hard to imagine Nicole Kidman being asked to tolerate.

While her old friend Ray started pinning up her hair, Cheung ate a bowl of rice noodles and someone put in front of her a Hong Kong sweet -- a deep-fried French toast sandwich with peanut butter slathered in between, which she snacked on as Ray finished up. Cheung, who’d shown up in black clogs, jeans and a long-sleeved brown T-shirt, disappeared for an instant, returning in a slinky black dress for the shoot. It was a rapid-fire transformation that suddenly revealed the single curving line of her body.

In the next room, the shooting started, with Cheung holding the cellphone up to her face, propping one leg on a box, hoisting the dress up to show some leg, improvising on the various attitudes a cellphone can apparently inspire. Chatting between shots, Cheung talked about all the traveling she does, the regular 12-hour flights between Hong Kong and Paris, where she found an apartment a few years ago to escape the press. For most of her life, she has lived somewhere between two cultures: when she was 8, her family moved to Kent, England, where she lived until she was discovered on the street on a brief visit to Hong Kong when she was 17.

“No matter where I’m going, I feel like I’m leaving something behind,“ she said. “Every time I get on a plane, I cry. The flight attendants on Cathay Pacific must think I’m mad.“ She laughed and did an imitation of herself sobbing into her flight pillow.

To Cheung, it seems unavoidable that an actress be “sad deep down,“ not so much as a job requirement but as a result of the job itself. Through the roles, she said, “you experience a lot more pain than normal people -- your mom dies, your dad dies, your boyfriend chucks you, you live in the street, and you’re really going through these emotions. You’re trying to know what it feels like to watch a man die in front of you, as if you’ve really lived it. Once that division is gone, it gets blurry -- you look back at a shoot and think, was I really that sad because in the film my boyfriend didn’t like me -- or was it something else, something real?“

She dashed off for a few more moments of posing, all smiles and allure, before returning to finish her earlier thought. “I think a lot of my sadness has to do with my mother,“ she said, giving the outlines of her mother’s difficult life: an unwanted girl, she spent her days as a young child roaming the streets because her parents wouldn’t let her inside except to sleep; she married a man who abandoned her for another woman and left her a single mother.

Someone from the shoot called to Cheung, and she flashed a bright smile. “Sorry,“ she said, heading back to the shoot, untouchably glamorous once again. On a computer screen someone enlarged a close-up of Cheung’s face resting on her hand, as the cameras continued to keep shooting, and the image stayed there for the rest of the shoot. It was a shot of a flawless, serious face, but a face that also looked ambiguously profound, the kind of face onto which its admirer could project seduction, or contemplation, or defiance, or sorrow.

Being a Hong Kong star has some of the advantages of being a Hollywood star, among them comparative luxury. Cheung’s well-situated Hong Kong apartment is done up simply in natural woods and elegant beige, its floor-to-ceiling windows opening onto a stunning view of Repulse Bay below. The windows in the back of the apartment, tinted a dark color, reflect the downside of such celebrity: not long after Cheung moved in, photos of her inside her home started appearing in the local tabloids, shot from a strip of road half a mile away.

“If I was drinking something, they said, ’Oh, she got dumped, she’s so miserable she’s turning to drink,“’ she said, pulling the shades down on that window as the sun set. “Or if my mother and sister came over, they said, ’She’s so miserable she needs her family to support her through this hard time.“’ Cheung had the window treated, but the paparazzi -- who treat her particularly harshly because she rarely gives interviews -- kept up the bad press. One local magazine shot her current boyfriend leaving the apartment, then badly photo-shopped the image so it looked as if he were making an obscene gesture to photographers with his hand. Waiters and restaurateurs are forever tipping off the press so that when Cheung tries to leave a restaurant, a phalanx is waiting for her.

Even Assayas, from whom she’s been separated for years, can’t cross a hotel lobby in Shanghai without being swarmed, because of his former association with Cheung. “In China, they care even more about their stars than in America,“ Assayas said, “and they’re also less shy about approaching them. I don’t know what it is. It’s less of an individualist society, maybe -- it’s like they feel their stars belong to them, are part of the family -- they’re someone in the family who made good, and they feel they belong to them.“ Assayas told me a story about accompanying Cheung to a restaurant and escorting her to the door of the ladies’ room. “She opened the door, the door closed behind her -- and then I just heard this girl start screaming,“ he said.

The costs of Cheung’s celebrity don’t come, however, with all the perks that offset those inconveniences for Hollywood stars. Her apartment is exquisitely placed but hardly vast, and no entourage follows her from shoot to shoot; on set, no luxury trailer allows her to get in character amid down throw pillows and freshly cut flowers. No one so much as tells her she’s fabulous, she said, laughing, which is partly a cultural difference. “Words like ’fabulous,’ ’wonderful,’ ’great,’ ’absolutely gorgeous’ -- they don’t exist in Cantonese. It’s good, or it’s O.K. That’s it. It’s very blunt, Cantonese. I appreciate that there are no fake words, but it’s hard to switch channels, sometimes, after I’ve spent time in France. I’m just learning to use more generous words myself -- but you know, ’gorgeous’ -- I just can’t go to that extreme.“

Cheung said she never wanted to be a movie star: she wanted to be a hairdresser. In the Western narrative of celebrity, the star burns for fame, works for it, dreams of it. Cheung, by contrast, was discovered on the street while visiting Hong Kong with her mother, then anointed the traditional Hong Kong way, through a beauty contest. Her fame seems disposable to her, even baffling. A kind of respectful acclaim, the kind musicians and authors and artists enjoy, would suit her better. It is not surprising to learn that Hollywood’s more arbitrary systems are totally alien to her: for example, the dance of an agent soliciting scripts that his celebrity client will never get around to reading. Even something as basic as the audition is unfamiliar terrain. In Hong Kong, she has been handed every role she has played since she was 18.

Assayas says he thinks that for Cheung’s own personal satisfaction, she has to keep making films in the West, to stretch herself and her acting, especially now that the Hong Kong film industry is in serious decline. He recognizes that the roles aren’t there; that’s why he wrote “Clean,“ even as the relationship was ending, to showcase the talent that has nothing to do with cheongsams or Asian femininity. American producers do occasionally send Cheung scripts, but the independent films are always about, as she put it, “ABC’s,“ or “American-born Chinese,“ struggling with their identity, and the Hollywood scripts feature dragon ladies or Chinatown mafia molls or martial artists or mysterious fortunetelling women. Right now the West, whether it’s New York or Paris, represents freedom for Cheung, and to sacrifice that anonymity for an uninspiring role would be folly.

“Especially since Cannes, I have a nice feeling out in Hong Kong -- like Maggie is ours, and we’re proud of her,“ she said. Shown a script for “X2: X-Men United“ a few years back, she declined to pursue it, uninterested in the film itself. “If I start making films like that, they won’t be proud,“ she said. “I’d feel like I was cheating. And I don’t want half the world -- we have 1.3 billion people in China -- to know I’m cheating. That matters to me. I have more pride than that.“

Part of this disparity can be attributed to simple demographics: African-Americans represent 13 percent of the American population, Latino-Americans 14 percent, while Asians account for about 4 percent. But filmmakers don’t even represent demographics faithfully, argues Jeff Yang, the author of “Once Upon a Time in China,“ a book about Chinese cinema. “Even in a movie set in the greater Bay Area,“ he says, “where one out of three people is Asian-American, if you just look at the background scenes, the bystanders, there are almost no Asians at all. That’s not just politically incorrect -- it’s fundamentally, demographically, incorrect.“

Janet Yang (no relation to Jeff), who produced “The People Vs. Larry Flynt“ and “The Joy Luck Club,“ contends that geography and history place Asian actresses too far outside the range of the girl next door, practically a prerequisite for female superstardom in this country. “Asia has been perceived as the enemy for many years,“ she adds. “Look at all the past major wars -- World War II, Korea, then Vietnam. There’s this crazy, deep-rooted bias.“ At the time she produced “The Joy Luck Club“ in 1993, Yang thought the film was a breakthrough; now, she says, studios are even less likely to finance such a film, given the absence of a name-brand, non-Asian star. Richard Hicks, the president of the Casting Society of America, says he proposes Cheung to directors with some regularity: half the time, he says, logistics get in the way -- “can we get her here by Thursday?“ -- but just as often his clients aren’t interested in casting an Asian.

Cheung, for her part, has never been driven to disprove American audiences’ stereotypes of Asian performers. To the contrary, she hasn’t made much of an effort to break into Hollywood. She has never come to Los Angeles just to make the rounds and rarely makes herself available for auditions. Given the scarcity of roles she’d like to play, it has hardly been worth it to her to pursue Hollywood success, she said; her current schedule is demanding enough. When I met with her in Toronto, Cheung had made the 17-hour trip from Hong Kong to Canada for just four days and was quickly heading back for some professional obligations: a promised appearance at the opening of a store in Shanghai for Louis Vuitton, and then a couple of days of shooting for some mobile-phone ads and commercials for the Hong Kong audience.

Cheung’s face is everywhere in Hong Kong. Head to the pharmacy, and she smiles at you from an Oil of Olay promotional ad behind the counter. Walk by the newsstand, and she’s on the cover of Chinese Elle and on the billboards at the bus stop. An ad campaign she did for Ericsson hand-held phones in the late 90’s was so successful it was cited as a case study in the Harvard Business Review. An entire row of DVD’s is devoted to her at the massive HMV on the way to Victoria Park. Having significantly reduced the brutal pace of her filmmaking, Cheung continues to take on numerous promotions, figuring that it’s easier to make money in a few days of empty work than in a few months of another action film.

In September, when I visited Cheung in Hong Kong, she had just returned from the Vuitton party in Shanghai -- a disaster, she said, with photographers popping out of nowhere at the arrival of her current boyfriend, Guillaume Brochard, a Frenchman with a jewelry business. She enjoyed only a few days of rest before the shoots for the mobile-phone ads. Out late the night before, she looked tired but still a good 10 years younger than her age. “They don’t know I was out last night,“ she whispered in English, as the mobile-phone reps scrambled around, trying to find appropriate pieces of wardrobe, while a makeup artist tended to her.

Cheung, who helped design her own theatrical makeup in “Hero,“ occasionally took one brush or another from the makeup artist to do the work herself. Although she clearly knows what she’s doing -- she teased her eyelashes out, transforming herself from the coolly disheveled Emily of “Clean“ to the elegant beauty of “In the Mood For Love“ -- makeup is her least favorite part of her job. During the shooting of “In the Mood,“ for 15 months she went to bed at 8 a.m., was picked up at noon to arrive on set by 1 p.m. for hair and makeup, then shot until late in the night, a schedule that it’s hard to imagine Nicole Kidman being asked to tolerate.

While her old friend Ray started pinning up her hair, Cheung ate a bowl of rice noodles and someone put in front of her a Hong Kong sweet -- a deep-fried French toast sandwich with peanut butter slathered in between, which she snacked on as Ray finished up. Cheung, who’d shown up in black clogs, jeans and a long-sleeved brown T-shirt, disappeared for an instant, returning in a slinky black dress for the shoot. It was a rapid-fire transformation that suddenly revealed the single curving line of her body.

In the next room, the shooting started, with Cheung holding the cellphone up to her face, propping one leg on a box, hoisting the dress up to show some leg, improvising on the various attitudes a cellphone can apparently inspire. Chatting between shots, Cheung talked about all the traveling she does, the regular 12-hour flights between Hong Kong and Paris, where she found an apartment a few years ago to escape the press. For most of her life, she has lived somewhere between two cultures: when she was 8, her family moved to Kent, England, where she lived until she was discovered on the street on a brief visit to Hong Kong when she was 17.

“No matter where I’m going, I feel like I’m leaving something behind,“ she said. “Every time I get on a plane, I cry. The flight attendants on Cathay Pacific must think I’m mad.“ She laughed and did an imitation of herself sobbing into her flight pillow.

To Cheung, it seems unavoidable that an actress be “sad deep down,“ not so much as a job requirement but as a result of the job itself. Through the roles, she said, “you experience a lot more pain than normal people -- your mom dies, your dad dies, your boyfriend chucks you, you live in the street, and you’re really going through these emotions. You’re trying to know what it feels like to watch a man die in front of you, as if you’ve really lived it. Once that division is gone, it gets blurry -- you look back at a shoot and think, was I really that sad because in the film my boyfriend didn’t like me -- or was it something else, something real?“

She dashed off for a few more moments of posing, all smiles and allure, before returning to finish her earlier thought. “I think a lot of my sadness has to do with my mother,“ she said, giving the outlines of her mother’s difficult life: an unwanted girl, she spent her days as a young child roaming the streets because her parents wouldn’t let her inside except to sleep; she married a man who abandoned her for another woman and left her a single mother.

Someone from the shoot called to Cheung, and she flashed a bright smile. “Sorry,“ she said, heading back to the shoot, untouchably glamorous once again. On a computer screen someone enlarged a close-up of Cheung’s face resting on her hand, as the cameras continued to keep shooting, and the image stayed there for the rest of the shoot. It was a shot of a flawless, serious face, but a face that also looked ambiguously profound, the kind of face onto which its admirer could project seduction, or contemplation, or defiance, or sorrow.

Being a Hong Kong star has some of the advantages of being a Hollywood star, among them comparative luxury. Cheung’s well-situated Hong Kong apartment is done up simply in natural woods and elegant beige, its floor-to-ceiling windows opening onto a stunning view of Repulse Bay below. The windows in the back of the apartment, tinted a dark color, reflect the downside of such celebrity: not long after Cheung moved in, photos of her inside her home started appearing in the local tabloids, shot from a strip of road half a mile away.

“If I was drinking something, they said, ’Oh, she got dumped, she’s so miserable she’s turning to drink,“’ she said, pulling the shades down on that window as the sun set. “Or if my mother and sister came over, they said, ’She’s so miserable she needs her family to support her through this hard time.“’ Cheung had the window treated, but the paparazzi -- who treat her particularly harshly because she rarely gives interviews -- kept up the bad press. One local magazine shot her current boyfriend leaving the apartment, then badly photo-shopped the image so it looked as if he were making an obscene gesture to photographers with his hand. Waiters and restaurateurs are forever tipping off the press so that when Cheung tries to leave a restaurant, a phalanx is waiting for her.

Even Assayas, from whom she’s been separated for years, can’t cross a hotel lobby in Shanghai without being swarmed, because of his former association with Cheung. “In China, they care even more about their stars than in America,“ Assayas said, “and they’re also less shy about approaching them. I don’t know what it is. It’s less of an individualist society, maybe -- it’s like they feel their stars belong to them, are part of the family -- they’re someone in the family who made good, and they feel they belong to them.“ Assayas told me a story about accompanying Cheung to a restaurant and escorting her to the door of the ladies’ room. “She opened the door, the door closed behind her -- and then I just heard this girl start screaming,“ he said.

The costs of Cheung’s celebrity don’t come, however, with all the perks that offset those inconveniences for Hollywood stars. Her apartment is exquisitely placed but hardly vast, and no entourage follows her from shoot to shoot; on set, no luxury trailer allows her to get in character amid down throw pillows and freshly cut flowers. No one so much as tells her she’s fabulous, she said, laughing, which is partly a cultural difference. “Words like ’fabulous,’ ’wonderful,’ ’great,’ ’absolutely gorgeous’ -- they don’t exist in Cantonese. It’s good, or it’s O.K. That’s it. It’s very blunt, Cantonese. I appreciate that there are no fake words, but it’s hard to switch channels, sometimes, after I’ve spent time in France. I’m just learning to use more generous words myself -- but you know, ’gorgeous’ -- I just can’t go to that extreme.“

Cheung said she never wanted to be a movie star: she wanted to be a hairdresser. In the Western narrative of celebrity, the star burns for fame, works for it, dreams of it. Cheung, by contrast, was discovered on the street while visiting Hong Kong with her mother, then anointed the traditional Hong Kong way, through a beauty contest. Her fame seems disposable to her, even baffling. A kind of respectful acclaim, the kind musicians and authors and artists enjoy, would suit her better. It is not surprising to learn that Hollywood’s more arbitrary systems are totally alien to her: for example, the dance of an agent soliciting scripts that his celebrity client will never get around to reading. Even something as basic as the audition is unfamiliar terrain. In Hong Kong, she has been handed every role she has played since she was 18.

Assayas says he thinks that for Cheung’s own personal satisfaction, she has to keep making films in the West, to stretch herself and her acting, especially now that the Hong Kong film industry is in serious decline. He recognizes that the roles aren’t there; that’s why he wrote “Clean,“ even as the relationship was ending, to showcase the talent that has nothing to do with cheongsams or Asian femininity. American producers do occasionally send Cheung scripts, but the independent films are always about, as she put it, “ABC’s,“ or “American-born Chinese,“ struggling with their identity, and the Hollywood scripts feature dragon ladies or Chinatown mafia molls or martial artists or mysterious fortunetelling women. Right now the West, whether it’s New York or Paris, represents freedom for Cheung, and to sacrifice that anonymity for an uninspiring role would be folly.

“Especially since Cannes, I have a nice feeling out in Hong Kong -- like Maggie is ours, and we’re proud of her,“ she said. Shown a script for “X2: X-Men United“ a few years back, she declined to pursue it, uninterested in the film itself. “If I start making films like that, they won’t be proud,“ she said. “I’d feel like I was cheating. And I don’t want half the world -- we have 1.3 billion people in China -- to know I’m cheating. That matters to me. I have more pride than that.“

bluedolphin

Active Member

- Joined

- Jan 13, 2006

- Messages

- 4,733

- Reaction score

- 4

Cheung often spends her nights e-mailing friends until 5 in the morning rather than going out on the town or to awards ceremonies or benefits. Occasionally, though, she meets up with friends at a restaurant with a private room. Toward the end of my visit, she picked me up, along with her boyfriend, in a van with covered windows and a driver who took us across the bay to the peninsula side of Hong Kong. Cheung, in sunglasses and boots, exited the car and started making the half-block walk toward the door. Around her, people started walking as if in slow motion, or stopped in their tracks altogether, so that it looked as if Cheung were moving at double speed. We took an elevator up 20 flights to Aqua, a sleek restaurant with interior spaces divided by doors that silently slide open upon approach and dizzying views of the glittering Hong Kong skyline beyond the bay, like New York’s seen through a magnifying glass, perfect and arrogant and untouched.

“A couple of weeks ago, I was in a room like this, and suddenly it was like one of those gangster movies, you know?“ Cheung said, animated and confiding. “The door flew open, and then“ -- she shaped her hand like a machine gun -- “Bang, bang, bang, bang, bang! All these light bulbs started flashing. And then they were gone. My friends and I were like, What just happened?“

As Brochard chatted with a friend of Maggie’s who’d just arrived, Cheung replied to a few last questions. Other than now -- she and Brochard seem particularly content -- when had she been happiest? Cheung thought for a moment, then described a time when she stopped acting for a long stretch and came to the States with a boyfriend, crashing at the home of one of his friends. With her boyfriend, Cheung went camping, stayed in hostels, learned to play a good game of pool and went bowling. “It was heaven,“ she said. “We were in Los Angeles. And we could go anywhere. No one had any idea who I was.“

“A couple of weeks ago, I was in a room like this, and suddenly it was like one of those gangster movies, you know?“ Cheung said, animated and confiding. “The door flew open, and then“ -- she shaped her hand like a machine gun -- “Bang, bang, bang, bang, bang! All these light bulbs started flashing. And then they were gone. My friends and I were like, What just happened?“

As Brochard chatted with a friend of Maggie’s who’d just arrived, Cheung replied to a few last questions. Other than now -- she and Brochard seem particularly content -- when had she been happiest? Cheung thought for a moment, then described a time when she stopped acting for a long stretch and came to the States with a boyfriend, crashing at the home of one of his friends. With her boyfriend, Cheung went camping, stayed in hostels, learned to play a good game of pool and went bowling. “It was heaven,“ she said. “We were in Los Angeles. And we could go anywhere. No one had any idea who I was.“

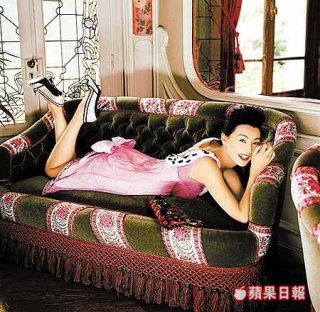

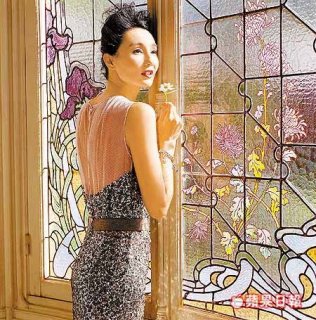

pictures: appledaily HK

Attachments

I looked through some posts with Chinese...and as Chinese as I am, I feel that it is not suitable for this largely international forum.

Nevertheless, I think Maggie Cheung has great style and fine face for her age. You know what? I think Maggie Cheung and Carina Lau are the only STARS remaining in the Hong Kong Cinema scene. She has such wonderful Parisan chic and elegance, and I think most people would agree.

And I am sorry to sound harsh, and please let me know if it is not acceptable---the movies that some of you have named are just bad taste.

Nevertheless, I think Maggie Cheung has great style and fine face for her age. You know what? I think Maggie Cheung and Carina Lau are the only STARS remaining in the Hong Kong Cinema scene. She has such wonderful Parisan chic and elegance, and I think most people would agree.

And I am sorry to sound harsh, and please let me know if it is not acceptable---the movies that some of you have named are just bad taste.

christina126

Active Member

- Joined

- May 20, 2005

- Messages

- 7,315

- Reaction score

- 1

she looks amazing in that Chanel dress!

bluedolphin

Active Member

- Joined

- Jan 13, 2006

- Messages

- 4,733

- Reaction score

- 4

i love you maggie~~

Similar Threads

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)