You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

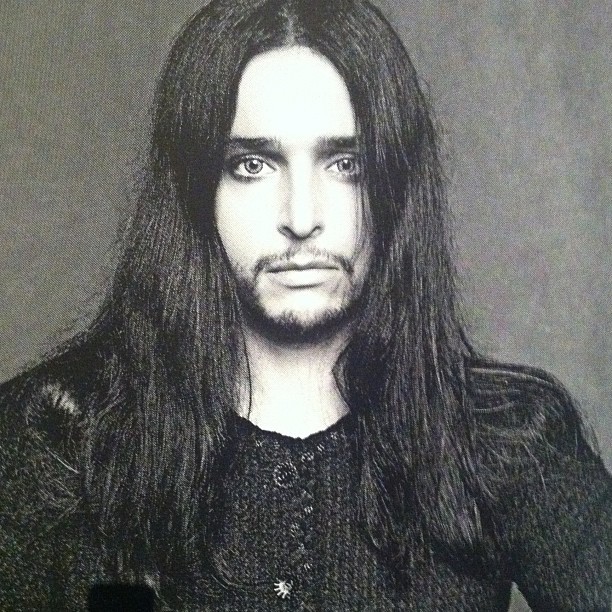

Olivier Theyskens - Designer

- Thread starter Ghost

- Start date

Designer Olivier Theyskens attends Dior and The Weinstein Company's Opening Of "Picturing Marilyn" at Milk Gallery on November 9, 2011 in New York City. (November 8, 2011 - Photo by Gary Gershoff/Getty Images North America)

MissMagAddict

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Feb 2, 2005

- Messages

- 26,621

- Reaction score

- 1,353

JuiceMajor

Active Member

- Joined

- Jul 8, 2005

- Messages

- 4,509

- Reaction score

- 1

great personal style!

intothegloss.comBackstage at the Theyskens’ Theory show in February, the soft-spoken French hairstylist Odile Gilbert paused to offer a succinct and rather unusual quote about the models’ transformed appearances: “Olivier has very strong opinions about how the girls should look…he’d like for them to look like him.”

On a recent sunny afternoon in Theyskens’ Meatpacking District atelier, I asked the designer about Gilbert’s comment, as well as his thoughts on beauty.

“That’s a way of making it short. [Laughs] It’s very funny, because actually I’ve been understanding this in me for these two last years. There’s been this shift in my mind that I basically…more and more put myself mentally in the place of girls. To imagine girls—would I like this if I was there? Would I want to dress like that? Would I like to wear that jacket? If I had that jacket, what pants would I really like to wear with it to look cool? That’s how I sort of evolved with designing. That’s maybe why—even the way I see my outfits even on the [Theyskens’ Theory] catwalk, they do not look like me as a designer, like I’m showing some impressive design. It’s more like me as I imagine I would like my clothes to be if I was a cool girl. It’s very different from before, because it’s less seen from outside. It’s less that I look at the girl from outside, as a figure. It’s a mental shift, I think.

For beauty, I’ve been having a hard time saying to the makeup artist, ‘Let’s put some…’ I feel uncomfortable more and more with makeup and girls. It’s maybe just the moment right now. It’s weird, the way we choose to wear makeup around the eye, and the lips. I got rid of almost everything at the last show—it almost had nothing, just a bit of some silver shine. It was not linear makeup some place, like a drawing. I’m more attracted by the way you can color your hair, and have a little skin tone and shine, but not like a faking of design, like re-designing your eye. It’s very weird to me.

For a time, when I was in Paris, I was putting a lot of kohl on myself all the time because I liked the Afghan eye, you know? Putting it just inside the eye. It was basically protecting against infections—it’s protection in the desert, and all. It evolves, it’s not permanent sort of ink…it makes a beautiful eye, in a way. I’ve stopped since I’ve started seeing the more young pop artists, guys, wearing eyeliner. I would not really wish to have it now.

I think androgyny saved me from being a person with a complex. As a kid of the 80’s, I had always on my mind that the beautiful, good-looking guy was the prototype of the 80’s guy, who was sort of like, this huge, big, beefy guy with short hair—what I would never be. And it was weird, because in the early 90’s, all these magazines started—the coolest magazines, like The Face, i-D, all these magazines showed up and put on the qualities of androgyny. It was not just the look, it was also the people: the guys that looked more feminine, the girls that had some tough aspects. We entered that era where androgyny became more fashionable. By seventeen, I sort of felt like I was happy with the physique I had, just right in time. [Laughs] I was really happy! And the whole time I had eczema on my face, you know, bad skin on my eyes. It was tough. I mean, I was feeling like I was a little ugly man. [Laughs] So I was like, ‘I actually look cool!’

I’ve never really been a part of a group, really. I was more like ‘Olivier the drawer, the dreamer,’ [Laughs] I like that. It’s always been like that. I had always wished to have long hair, since I was a very very little child. I remember really really early memories, I would always put anything fringy—like a fringe blanket—on my head. Even at the restaurant I would put my napkin on my head and imagine it’s like hair. [Laughs] I was always like that. Always. But I had to always cut it. I finally started to grow it out when I was a teenager. It was the time of Nirvana, Kurt Cobain, and at the time I was really into Nirvana and The Cure and all these guys. So the thing was always to use shaving blades, and getting it a little bit trashy. So that was my thing. I did it myself; there was not really a hairdresser in the neighborhood who liked making that. Now a lot of times Odile cuts it before the shows. When we work on the fittings for the hairdressing, after we finished that on the model, she’ll quickly just cut the ends. A lot of times I’ll attach it on top of my head like her. I think sometimes you have your little fashions.

I don’t do anything special to my hair. I try to use products that have no crazy chemicals—parabens, all these things. I’m using these basic ecological shampoos. I like for example, Australian Organics—I buy it in Paris—or these kinds of things for hair. You don’t need strange chemicals to clean…you’re not really dirty, you just need some components that get rid of oil. I really wash my skin—like, every morning, every night. I always use products with no bad chemicals. I like La Roche Posay, I think it’s good. But I don’t have one brand that I’m looking after. There’s this good brand in Paris called A-Derma. That is very good; I always have bigger bottles so I can keep it. It’s really the best, I think. I don’t think it exists here in New York. I always moisturize my skin—I think it’s good for the skin. The upper layer of the skin is dead, actually—dead cells. But it’s good to moisturize it anyway I think—I feel better. Otherwise I sort of feel tight.

My hair was darker when I was a kid, I think. But I’ve never colored it; I don’t experiment with hair color. I even like the gray hair here. The gray just started happening; I’m kind of lucky with that. I don’t know if I’ll do anything about it. Actually, what I don’t like is when the structure of the hair changes, more than the color. The hair, when they go gray, some people are lucky, they have their hair getting gray but keeping the same texture. And some others, the hair becomes like a rebel. I think mine is like that. You can see this sort of crooked curl that’s very weird. I was reading they found a molecule that is stopping the chain reactions that create the gray hair. They found a molecule to preserve the color of your hair, which is kind of interesting, but it will take a while to synthesize that. It’s always interesting, but for sure, one day. My eyebrows are natural, but I take care if I have a strange hair growing some place. [Laughs] One time, I had a very weird thing happening. I had one hair growing through the middle of my forehead! It was very thin, I think it grew in two days, like, three inches long. It was horrifying! I was like, ‘What is this? A hair growing on my face!’ I had that one time. I still look for it after a while, if it will ever come back one day. Or maybe it was a one shot experience.

I think getting older is an experience. [Laughs] The funny thing is, that I remember being younger and thinking, ‘Oh, I’m going to match it well,’ and nobody is. I’m thirty-four—and sometimes I see my hand, and I see there is an evolution. I’m witnessing that I’m getting older, and that’s okay. I think the experience is very interesting. I’m doing yoga, and I like to see that you have people who are really old doing this. Like, they do the same lessons as I do, and relatively well—guys who are sixty-five, and they still do it very well. I see their bodies, they are all firm muscles and all of that. I think I should sort of pay attention to that, and keep myself in shape. I probably eat better than when I was younger. I’m also probably healthier since I really quit smoking, three years ago.

What’s good in New York is that you can get a cool manicure. I like it, it’s very pleasant—just clean and perfect fingertips. And sometimes I want a deep tissue massage. I don’t want to say where I go, because she’s always overbooked and I don’t want anybody to try my place—but she’s a very fantastic masseuse—she’s the treasure of masseuses. I go there if I feel like I’m sort of like blocking my shoulders—like, the movement of air around me could be blocking my neck very easily. It feels like the cold enters my neck to my spine and it blocks it all out. I have to be super careful, I always have a scarf in the office because in ten minutes I’m blocked. I wish I could practice yoga every two days, but I don’t find the time. So I have that frustration to really feel on top of my abilities and to have the experience of feeling complete in practicing. A lot of the time I’m sort of like, practicing to go back to the level I’m supposed to be. So you cannot really enjoy it properly—but at the same time it’s good for you, that’s all.

With food, I pay attention to the product I buy. If I’m buying—and this is very rare—[laughs] you will find me always reading the ingredients. In fact, I read more ingredients than books. I’m always looking after anything I can read, like, ‘Okay, no sugar added, please. No syrup, please. No tricky stuff, please,’ just simple good food. I hate this global food market. It’s disgusting. I’m horrified in what I see in these poor looking-products, what is behind it. So I’m trying to find always simple—no tricky additives. I think it’s good to eat not too much meat. I don’t do that because of the concept of meat, I do it because I think it’s healthier to not exaggerate with meat. I mean, we can think we’re powerful, but when we were prehistoric, we were not great hunters. We were better eating all the veggie stuff around us, and a little bit of meat and fish. It’s true of our species.”

I posted some pictures of [Caroline Trentini's] wedding here. Apparently there's a feature on it in the May issue of US Vogue, and her dress was designed by Olivier Theyskens

Last edited by a moderator:

Designer Olivier Theyskens and model Caroline Trentini attend the "Schiaparelli And Prada: Impossible Conversations" Costume Institute Gala at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on May 7, 2012 in New York City. (May 6, 2012 - Source: Dimitrios Kambouris/Getty Images North America)

Psylocke

Active Member

- Joined

- Dec 1, 2009

- Messages

- 10,980

- Reaction score

- 27

I really love the dress he designed for the Met Ball. I would never have thought I'd ever say that about a denim dress! But I love the silhouette paired with that cropped lace top. The faded denim effect really works here, too. So gorgeous. And Olivier himself also looked great.

Olivier Theyskens and Constance Jablonski attend the 2012 CFDA Fashion Awards at Alice Tully Hall on June 4, 2012 in New York City. (June 3, 2012 - Source: Larry Busacca/Getty Images North America)

Olivier Theyskens attends Chanel's:The Little Black Jacket Event at Swiss Institute on June 6, 2012 in New York City. (June 5, 2012 - Source: Jamie McCarthy/Getty Images North America)

Lee MG Tisci

Active Member

- Joined

- Sep 3, 2011

- Messages

- 2,410

- Reaction score

- 0

Bernadette

Active Member

- Joined

- Aug 20, 2013

- Messages

- 1,880

- Reaction score

- 8

Bernadette

Active Member

- Joined

- Aug 20, 2013

- Messages

- 1,880

- Reaction score

- 8

Bernadette

Active Member

- Joined

- Aug 20, 2013

- Messages

- 1,880

- Reaction score

- 8

BoF Exclusive | Olivier Theyskens Speaks to Dorian Grinspan, Founder of Out of Order Magazine

By Dorian Grinspan 22 May, 2013

Today, BoF brings you an exclusive interview with Olivier Theyskens, courtesy of Out of Order magazine, in which the designer discusses his work for Rochas, Nina Ricci and Theory, what the future holds, and why he used to want to be a girl

Olivier Theyskens | Source: Out of Order

NEW HAVEN, United States — Whilst matriculating as a third year history major at Yale and finding himself with “not a lot to do,” 20-year-old Dorian Grinspan, a Paris native and part-time model, founded Out of Order, a highly atypical student fashion magazine now stocked at influential retailers, including Colette and Opening Ceremony. The magazine’s 244-page, adolescence-themed sophomore issue features a cover by Larry Clark, images of Arizona Muse with her son Nikko, and in-depth interviews with Olivier Theyskens, Angel Haze and Ryan McGinley, as well as advertising from brands including Stella McCartney, Bulgari and Jason Wu.

In a global exclusive, BoF brings you Grinspan’s interview with Theory designer Olivier Theyskens, who along with founding his own label, has held creative director positions at Rochas and Nina Ricci, prior to his current appointment. The designer discusses the differences between his work for Rochas, Nina Ricci and Theory, what the future holds and why he used to want to be a girl.

OOO: I looked up your Wikipedia page, and the first thing it says was that when you were younger, you wanted to be a girl.

OT: I remembered that I loved playing with clothes and playing with fabrics. I loved beautiful things, beautiful clothes. I loved to dress in costumes. I remember, at the time, saying I wanted to be a girl because I loved princesses. I loved to look at the female characters of any movies. I was very attracted by that. I always felt women could incarnate a really fascinating mystery for me. From Hollywood to the 1980s military hero girls, I always saw girls as these amazing figures. I always admired these figures.

Did women play a large role in your life growing up?

Yes, my mother had a few sisters, and I loved my aunts. I have two older brothers, and my sister was not very girly. She was a bit of a tomboy. I really admired older women, too. I actually didn’t admire my girlfriends at school the way I admired grown-up women, either real-life ones or characters in a movie. My imagination was always more stimulated by people who were more grown-up.

What would they inspire you to do?

It’s more that I loved the world I was imagining these women in. I also did this with men. I loved to admire adulthood, the way they were dressing, and the way they acted together. It was not at all the way I behaved with my friends, so it was a big mystery to me.

Was it more about the relationships or about the appearance of adulthood?

As a child, I liked how you could see more intimate moments in movies with adult characters. I was really fascinated by scenes that would reveal personal qualities within the characters. I don’t remember what movie this was from, but there was a man in a train. He was on his own in the cabin, and he was semi-undressed, and he was in his own little masculine world. That fascinated me: the small, hidden elements in a secret adult world.

Would you try to recreate them with you in it?

No, but it’s probably how I became interested in clothes.

Did that change when you were growing up, or did it evolve in any way?

I still see a lot of this in other people. I like to imagine that they have these more intimate parts, their own clothes, and their own world. It’s fascinating to me. A lot of times, I wish I could ask people: “What other stuff do you like to wear? What is your intimate world?”

How did that inform your early work?

I like to think that what I do will enter that person’s world. I know that my job is to influence people with a world I create. The ideas are there but they’re split up; they’ve exploded into a million pieces, and it’s up to me to put it together, creatively, in a way that fits.

Your work at Theory is very different from the kind of designs you would make for your label, Rochas, or Nina Ricci. What has changed since then?

I approach my designs with just as much intensity. A lot of people see differences between what I used to do then and now, but on a day-to-day basis, my approach is still the same. I put the same amount of thinking into it, and I have the same concern in getting the result I’m looking for. The only difference is that my creativity flows differently. For example, a lot of the time people ask me to do dresses, but in the present context, I refuse to make too many because it just doesn’t fit with what I want to do right now, or with how I see the brand evolving.

Why not?

Because it wouldn’t sit the right way. I think my creativity is very connected with my subconscious and intuition and my own inner character. So maybe my subconscious doesn’t let certain things flow, because they wouldn’t sit properly. It doesn’t feel right. I’m always looking to feel that what I do is right, for the right place, and at the right time.

Do you ever look back?

Yes, I have to sometimes, like in an interview or a discussion with someone. A few times I’ve had to browse back into the past, and it’s so weird for me. It’s so far. Everything feels so far away.

Do you go back to before you even started designing?

I have so many drawings at my parents’ place from when I was a teenager or a child, or even early drawings from my career. I have to go through it at some point, but to me, there is nothing more boring. It might be interesting to see some of the drawings, but it’s such a boring task to go through these millions of pages of stuff that I don’t even remember making.

Do you ever look at them?

No. One of the few times I had to look back was when I had to prepare a mini-film on my work. I went through my drawings. I wanted to archive my work from Ricci and Rochas, so I had to put all the drawings into boxes, and that was such a pain in the ***. It was so much stuff, and I don’t really like much of it. I like to introduce elements of the past in my work—like elements of culture and knowledge—but I don’t like looking back to my early works.

Moving from your childhood to your adulthood, are you as fascinated by people around you now, or do you still look to generations ahead?

I think I’m more fascinated by being alone. It’s probably because I like to imagine things. Actually, even if I interact easily with people, I have to admit that I’m still very intimidated by others. Deep in me, I feel very, very shy in general about people that I’m with. I think that there is this human part, this personal part that I cannot seize, but I know it’s there. In our interactions with people, we tend to keep a distance. Emotions are one of the biggest focal points of my work. I am always obsessed with the feeling of emotion. I’ll design a girl in a black suit, but in my mind, the way I imagine she is—beyond the suit, there is a person with weird emotions. A lot of times, when I interact with adults, I like to imagine that there might be crushed emotions or deeper things going on.

If you were to look at yourself from the outside and perceive that intimate part of yourself, what would it be?

I don’t know. A lot of times, I’m told that people working around me, for example, are sometimes scared of me. That’s so weird to me. I think we’re in a world where there are a lot of preconceptions—people will think that you are a certain kind of person, or that you do things a certain way. Everybody has a preconceived point of view; they think of others as something that they’re not. But the way I see myself? I believe I am as mysterious as the way I see other people, in the end.

But if you were to give us some insight as to who you are, what would it be?

I am very brainy and obsessed about what I am doing. I’m always trying to do the best I can, but I often feel that it’s not as perfect as I want. I always have a little thing in me—it’s not a frustration, it’s more like a shaking feeling. I’m stressed about the fact that I cannot do something as well as I really want to. I have this feeling constantly. In the past few years, I’ve been taking better care of my health. I’m more conscious of my body, of that machine, than when I was younger.

If you had any lessons from when you were younger, what would they be?

Millions of little lessons. The things I’ve learned the most are always about the human element. A lot of what you do can excite people, but not everything you do can have a real impact. There is a marginalization between what you create and what actually works: people like to see things that excite them, but what they experience in life is often different from that. For example, even with myself, I like to see upscale designs, but I have a hard time wearing something too upscale.

As a designer, how do you reconcile both?

What I like, and what will always make me happy, is that I associate extremes in my work. For my first collection, I was obsessed with having the perfect black pants and very clean, invisible zips on the side. At the same time, I also wanted to do an incredible piece that was very visual and amazing, and nobody would probably ever wear it, save for an exceptional occasion—but I wanted to do it just because it was beautiful.

Do you get more excited about pieces that are not necessarily wearable or pieces that people wear and that you’ll see on the street tomorrow?

I think that even my most extreme designs are very wearable in a way, because they enhance the beauty of the body. I have a very weird relationship with more experimental designs. I experiment to bring creativity, but experimental designs are sometimes too bizarre, to the point where I cannot feel the body anymore. Holes on the shoulders are such a weird design. I’m more conservative than one might think. The stage dresses that I did were still tighter on the waist, revealed the body—they were like an absolute fashion figure. But I rarely did an asymmetric pleated or semi-pleated skirt. I have respect for people who design these kinds of things, but I am at a loss when I have them in my hands. It’s very conceptual.

How do you reconcile your previous experiences as a designer at Rochas or Ricci, where you had more freedom, with a brand like Theory, where you have to adhere to a certain budget or a certain image? Does it restrict your creativity in any way?

I feel like I work in the same conditions that I always have been in. I’m with people who believe in what I can bring to the evolution of their brand. I don’t feel like I ever accepted a restrictive job. I accepted to participate in the evolution and the building of the future of a brand, and for that, I have a responsibility to make that happen. It doesn’t even get reflected in the budget. I’m taking the responsibility together with them. Obviously, if I started to experiment or go crazy, of course we would have a conversation—but then I would say I agree, and it’s become too much. But even so, I’ve never experienced that, ever. Companies or groups of people—the most important thing is that you work together. And on a day-to-day basis, you see where you are and what you still have to do. It’s less about things that are restricting, and more about the fact that we have so much more to do.

How do you choose what to do?

It’s difficult to make that decision. We’ll have an intention of doing a certain jacket, and then that intention will evolve; then we suddenly feel it’s not the right fabric anymore, so we have to put it in a different fabric. This is the way we work. We really want to get at the best results, and it’s very organic. Right now, I could have eighty styles that are not very nice, or twenty styles that are perfect. And I don’t know yet where exactly we are going to be. It’s very organic.

How do you see yourself evolving from here?

The thing is, I feel like I have so many years to give. I have so much creativity to give, so I don’t know. It’s funny—if you read the Encyclopedia of Fashion and you see the designers listed, life is long. What I’ve also felt is that events make you change. You have to go to something else, and it’s sometimes unpredictable. This is what I felt when I left my own brand to do Rochas in Paris. It was after the economic crisis following September 11, and I had to make a decision at that time. It was a choice between a tough future for an independent, little brand, or bringing something to Paris that I was attracted to. I always felt that I made the right choice, to go with that experience.When I think of the future from this point on, I see a future connected to Theory, with the way the brand is going to develop, but I also know that you never know. I always feel that it’s important to be able to change, to evolve, to transform.

Is it hard to reinvent yourself multiple times a year?

No, I feel that we build on a lot of things that we are happy with. We are always trying to capitalize on energy and excitement. But we are always trying to bring something new, because otherwise there would be a frustration—a feeling that we are not changing enough. We need to feel we are changing, but we also need to capitalize on what we like. In my work, I always feel that there is a connection to the last work I did, but there is a step towards a new evolution. I never feel happy if I don’t feel that.

What’s your next step?

I want to be more focused. For example, the last collection felt a little bit like it was exploding, and I want to be more focused. I’m so happy with what we’re doing with Theory, and I want people to be more aware of how the brand is now evolving. It’s amazing. There was a need for change, a need for evolution. It took a while to do it, but now I’m very excited by it.

Source: businessoffashion.com

By Dorian Grinspan 22 May, 2013

Today, BoF brings you an exclusive interview with Olivier Theyskens, courtesy of Out of Order magazine, in which the designer discusses his work for Rochas, Nina Ricci and Theory, what the future holds, and why he used to want to be a girl

Olivier Theyskens | Source: Out of Order

NEW HAVEN, United States — Whilst matriculating as a third year history major at Yale and finding himself with “not a lot to do,” 20-year-old Dorian Grinspan, a Paris native and part-time model, founded Out of Order, a highly atypical student fashion magazine now stocked at influential retailers, including Colette and Opening Ceremony. The magazine’s 244-page, adolescence-themed sophomore issue features a cover by Larry Clark, images of Arizona Muse with her son Nikko, and in-depth interviews with Olivier Theyskens, Angel Haze and Ryan McGinley, as well as advertising from brands including Stella McCartney, Bulgari and Jason Wu.

In a global exclusive, BoF brings you Grinspan’s interview with Theory designer Olivier Theyskens, who along with founding his own label, has held creative director positions at Rochas and Nina Ricci, prior to his current appointment. The designer discusses the differences between his work for Rochas, Nina Ricci and Theory, what the future holds and why he used to want to be a girl.

OOO: I looked up your Wikipedia page, and the first thing it says was that when you were younger, you wanted to be a girl.

OT: I remembered that I loved playing with clothes and playing with fabrics. I loved beautiful things, beautiful clothes. I loved to dress in costumes. I remember, at the time, saying I wanted to be a girl because I loved princesses. I loved to look at the female characters of any movies. I was very attracted by that. I always felt women could incarnate a really fascinating mystery for me. From Hollywood to the 1980s military hero girls, I always saw girls as these amazing figures. I always admired these figures.

Did women play a large role in your life growing up?

Yes, my mother had a few sisters, and I loved my aunts. I have two older brothers, and my sister was not very girly. She was a bit of a tomboy. I really admired older women, too. I actually didn’t admire my girlfriends at school the way I admired grown-up women, either real-life ones or characters in a movie. My imagination was always more stimulated by people who were more grown-up.

What would they inspire you to do?

It’s more that I loved the world I was imagining these women in. I also did this with men. I loved to admire adulthood, the way they were dressing, and the way they acted together. It was not at all the way I behaved with my friends, so it was a big mystery to me.

Was it more about the relationships or about the appearance of adulthood?

As a child, I liked how you could see more intimate moments in movies with adult characters. I was really fascinated by scenes that would reveal personal qualities within the characters. I don’t remember what movie this was from, but there was a man in a train. He was on his own in the cabin, and he was semi-undressed, and he was in his own little masculine world. That fascinated me: the small, hidden elements in a secret adult world.

Would you try to recreate them with you in it?

No, but it’s probably how I became interested in clothes.

Did that change when you were growing up, or did it evolve in any way?

I still see a lot of this in other people. I like to imagine that they have these more intimate parts, their own clothes, and their own world. It’s fascinating to me. A lot of times, I wish I could ask people: “What other stuff do you like to wear? What is your intimate world?”

How did that inform your early work?

I like to think that what I do will enter that person’s world. I know that my job is to influence people with a world I create. The ideas are there but they’re split up; they’ve exploded into a million pieces, and it’s up to me to put it together, creatively, in a way that fits.

Your work at Theory is very different from the kind of designs you would make for your label, Rochas, or Nina Ricci. What has changed since then?

I approach my designs with just as much intensity. A lot of people see differences between what I used to do then and now, but on a day-to-day basis, my approach is still the same. I put the same amount of thinking into it, and I have the same concern in getting the result I’m looking for. The only difference is that my creativity flows differently. For example, a lot of the time people ask me to do dresses, but in the present context, I refuse to make too many because it just doesn’t fit with what I want to do right now, or with how I see the brand evolving.

Why not?

Because it wouldn’t sit the right way. I think my creativity is very connected with my subconscious and intuition and my own inner character. So maybe my subconscious doesn’t let certain things flow, because they wouldn’t sit properly. It doesn’t feel right. I’m always looking to feel that what I do is right, for the right place, and at the right time.

Do you ever look back?

Yes, I have to sometimes, like in an interview or a discussion with someone. A few times I’ve had to browse back into the past, and it’s so weird for me. It’s so far. Everything feels so far away.

Do you go back to before you even started designing?

I have so many drawings at my parents’ place from when I was a teenager or a child, or even early drawings from my career. I have to go through it at some point, but to me, there is nothing more boring. It might be interesting to see some of the drawings, but it’s such a boring task to go through these millions of pages of stuff that I don’t even remember making.

Do you ever look at them?

No. One of the few times I had to look back was when I had to prepare a mini-film on my work. I went through my drawings. I wanted to archive my work from Ricci and Rochas, so I had to put all the drawings into boxes, and that was such a pain in the ***. It was so much stuff, and I don’t really like much of it. I like to introduce elements of the past in my work—like elements of culture and knowledge—but I don’t like looking back to my early works.

Moving from your childhood to your adulthood, are you as fascinated by people around you now, or do you still look to generations ahead?

I think I’m more fascinated by being alone. It’s probably because I like to imagine things. Actually, even if I interact easily with people, I have to admit that I’m still very intimidated by others. Deep in me, I feel very, very shy in general about people that I’m with. I think that there is this human part, this personal part that I cannot seize, but I know it’s there. In our interactions with people, we tend to keep a distance. Emotions are one of the biggest focal points of my work. I am always obsessed with the feeling of emotion. I’ll design a girl in a black suit, but in my mind, the way I imagine she is—beyond the suit, there is a person with weird emotions. A lot of times, when I interact with adults, I like to imagine that there might be crushed emotions or deeper things going on.

If you were to look at yourself from the outside and perceive that intimate part of yourself, what would it be?

I don’t know. A lot of times, I’m told that people working around me, for example, are sometimes scared of me. That’s so weird to me. I think we’re in a world where there are a lot of preconceptions—people will think that you are a certain kind of person, or that you do things a certain way. Everybody has a preconceived point of view; they think of others as something that they’re not. But the way I see myself? I believe I am as mysterious as the way I see other people, in the end.

But if you were to give us some insight as to who you are, what would it be?

I am very brainy and obsessed about what I am doing. I’m always trying to do the best I can, but I often feel that it’s not as perfect as I want. I always have a little thing in me—it’s not a frustration, it’s more like a shaking feeling. I’m stressed about the fact that I cannot do something as well as I really want to. I have this feeling constantly. In the past few years, I’ve been taking better care of my health. I’m more conscious of my body, of that machine, than when I was younger.

If you had any lessons from when you were younger, what would they be?

Millions of little lessons. The things I’ve learned the most are always about the human element. A lot of what you do can excite people, but not everything you do can have a real impact. There is a marginalization between what you create and what actually works: people like to see things that excite them, but what they experience in life is often different from that. For example, even with myself, I like to see upscale designs, but I have a hard time wearing something too upscale.

As a designer, how do you reconcile both?

What I like, and what will always make me happy, is that I associate extremes in my work. For my first collection, I was obsessed with having the perfect black pants and very clean, invisible zips on the side. At the same time, I also wanted to do an incredible piece that was very visual and amazing, and nobody would probably ever wear it, save for an exceptional occasion—but I wanted to do it just because it was beautiful.

Do you get more excited about pieces that are not necessarily wearable or pieces that people wear and that you’ll see on the street tomorrow?

I think that even my most extreme designs are very wearable in a way, because they enhance the beauty of the body. I have a very weird relationship with more experimental designs. I experiment to bring creativity, but experimental designs are sometimes too bizarre, to the point where I cannot feel the body anymore. Holes on the shoulders are such a weird design. I’m more conservative than one might think. The stage dresses that I did were still tighter on the waist, revealed the body—they were like an absolute fashion figure. But I rarely did an asymmetric pleated or semi-pleated skirt. I have respect for people who design these kinds of things, but I am at a loss when I have them in my hands. It’s very conceptual.

How do you reconcile your previous experiences as a designer at Rochas or Ricci, where you had more freedom, with a brand like Theory, where you have to adhere to a certain budget or a certain image? Does it restrict your creativity in any way?

I feel like I work in the same conditions that I always have been in. I’m with people who believe in what I can bring to the evolution of their brand. I don’t feel like I ever accepted a restrictive job. I accepted to participate in the evolution and the building of the future of a brand, and for that, I have a responsibility to make that happen. It doesn’t even get reflected in the budget. I’m taking the responsibility together with them. Obviously, if I started to experiment or go crazy, of course we would have a conversation—but then I would say I agree, and it’s become too much. But even so, I’ve never experienced that, ever. Companies or groups of people—the most important thing is that you work together. And on a day-to-day basis, you see where you are and what you still have to do. It’s less about things that are restricting, and more about the fact that we have so much more to do.

How do you choose what to do?

It’s difficult to make that decision. We’ll have an intention of doing a certain jacket, and then that intention will evolve; then we suddenly feel it’s not the right fabric anymore, so we have to put it in a different fabric. This is the way we work. We really want to get at the best results, and it’s very organic. Right now, I could have eighty styles that are not very nice, or twenty styles that are perfect. And I don’t know yet where exactly we are going to be. It’s very organic.

How do you see yourself evolving from here?

The thing is, I feel like I have so many years to give. I have so much creativity to give, so I don’t know. It’s funny—if you read the Encyclopedia of Fashion and you see the designers listed, life is long. What I’ve also felt is that events make you change. You have to go to something else, and it’s sometimes unpredictable. This is what I felt when I left my own brand to do Rochas in Paris. It was after the economic crisis following September 11, and I had to make a decision at that time. It was a choice between a tough future for an independent, little brand, or bringing something to Paris that I was attracted to. I always felt that I made the right choice, to go with that experience.When I think of the future from this point on, I see a future connected to Theory, with the way the brand is going to develop, but I also know that you never know. I always feel that it’s important to be able to change, to evolve, to transform.

Is it hard to reinvent yourself multiple times a year?

No, I feel that we build on a lot of things that we are happy with. We are always trying to capitalize on energy and excitement. But we are always trying to bring something new, because otherwise there would be a frustration—a feeling that we are not changing enough. We need to feel we are changing, but we also need to capitalize on what we like. In my work, I always feel that there is a connection to the last work I did, but there is a step towards a new evolution. I never feel happy if I don’t feel that.

What’s your next step?

I want to be more focused. For example, the last collection felt a little bit like it was exploding, and I want to be more focused. I’m so happy with what we’re doing with Theory, and I want people to be more aware of how the brand is now evolving. It’s amazing. There was a need for change, a need for evolution. It took a while to do it, but now I’m very excited by it.

Source: businessoffashion.com

Last edited by a moderator:

Bernadette

Active Member

- Joined

- Aug 20, 2013

- Messages

- 1,880

- Reaction score

- 8

Bernadette

Active Member

- Joined

- Aug 20, 2013

- Messages

- 1,880

- Reaction score

- 8

The Comedown with Olivier Theyskens | Harper's Bazaar The Look S2.E4

Source: YouTube (Hello Style)

Similar Threads

- Replies

- 95

- Views

- 12K

- Replies

- 181

- Views

- 24K

- Replies

- 42

- Views

- 9K

- Replies

- 44

- Views

- 5K

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)