Alaïa’s heir apparel

After two decades in the business, Pieter Mulier was “done” with fashion. Then Richemont called.

Jo Ellison

Alaïa is not the most universally known name in fashion, nor is it the biggest house. Owned by Richemont, which bought a significant stake in 2007, Alaïa has 170 points of sale, and modest revenues (in 2017, it was estimated revenues were around €50mn, although the company says the number is “higher” than that today).

Yet in terms of reputational power and cultural influence, the house remains unparalleled. As Cher Horowitz explains to her mugger in Clueless, the Tunisia-born Azzedine Alaïa was “like, a totally important designer”. Born in 1935, Alaïa worked for Christian Dior, Guy Laroche and Thierry Mugler before founding his own label in 1981. And even if you are not familiar with the brand name, you will probably recognise its stretch-knit bodysuits, as worn by ’80s supermodels. Or the much-copied “skater”, a fluted, fitted minidress, or the corset belt that cinches waists into Edwardian proportions, or its distinctive tote bag perforated with a pretty daisy‑looking stamp. For nearly 40 years Azzedine, known as “papa”, occupied a position at the height of craftsmanship. His death in November 2017, while not entirely unexpected, left a gaping vacuum at the brand.

Pieter Mulier was considering a job offer from a furniture company when the call came in from Richemont, in 2020. The designer had not long returned to his home in Antwerp, having reached an “amicable” parting with his former employers at Calvin Klein. He had spent two decades working in the heart of fashion. And he was “done” with all of it.

“I was done with the mathematics,” says Mulier, over an espresso outside the Alaïa headquarters on Rue de Moussy, in Paris’s Marais district. “Done with the people. Done with the big teams, and done with finding the energy to give to the team and being a kind of creative clown.

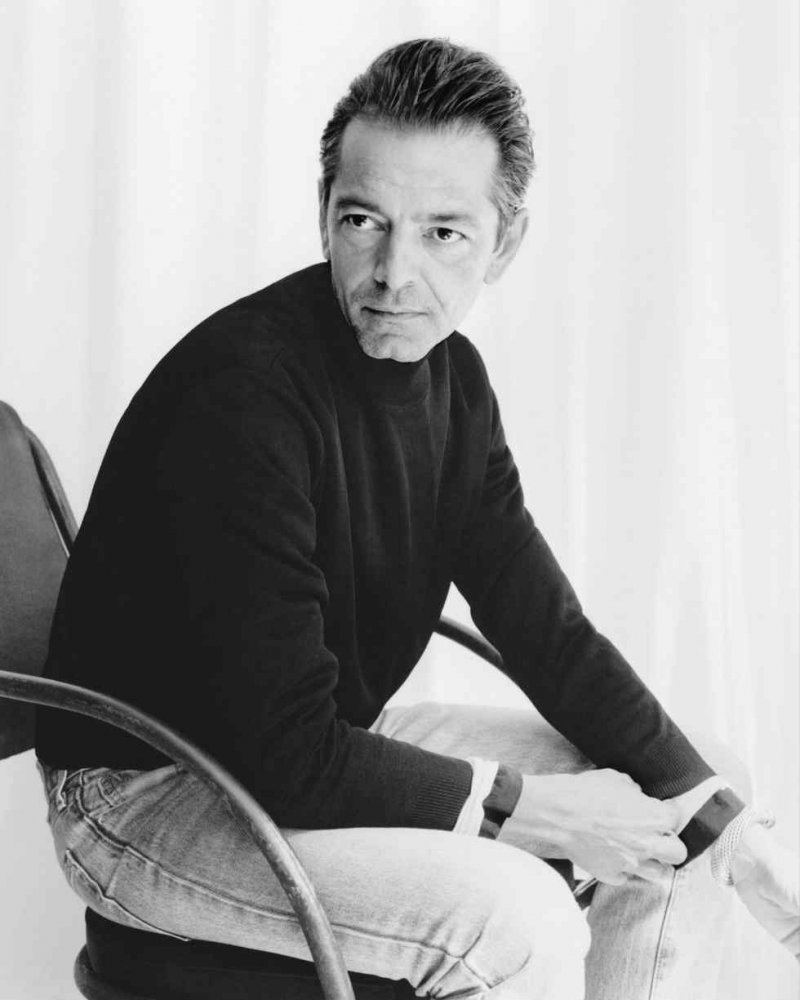

“I was done with finding the energy to give to the team and being a kind of creative clown” Pieter Mulier “Honestly, I didn’t want a profession any more,” says the 43-year-old designer, who is slight and puckishly handsome, with narrow features and a knowing grin. He is dressed in a navy Prada overcoat despite it being an exceptionally humid afternoon. Even he realised, however, that the house of Alaïa was a rare jewel: a tiny couture-like studio with a clutch of clients who were passionate, deep-pocketed and fiercely loyal. Immediately he stopped all other conversations. He only wanted this – an opportunity like Alaïa, he says, was a “once in a lifetime thing”.

Mulier’s job offer to be its new creative director came with a simple mandate: to protect the brand. “There were no targets, no merchandisers, nothing,” he says. “They just said you have to maintain the brand’s already high reputation, and we would like the name to be more well-known.”

“Pieter had amazing experiences, through a great diversity of brands,” says Myriam Serrano, the Alaïa CEO. And while he may not have been given specific targets, Serrano comments: “He understood the stakes.”

Mulier was not an Alaïa disciple. His career till then had cleaved to the success of another man – the Belgian designer Raf Simons, with whom Mulier had started working as an intern while studying architecture, before deciding to study fashion and redirect his whole career. Working at Simons’s namesake menswear label, Mulier quickly ascended through the ranks. He followed Simons to Jil Sander in 2006, and then, in 2012, became his right‑hand man for four years at Dior. Readers may recall Mulier from the fashion documentary Dior and I, which follows preparations for the first couture show: as the persuasive interlocutor between the febrile Simons and the rambunctious head seamstresses, the charming consigliere steals every scene.

But while Mulier’s gift for communicating would be his superpower, his experience had left him feeling spent. By the end of his tenure as creative director at Calvin Klein (where he went with Simons after Dior for two years), Mulier had no plans to set foot inside a fashion house again. In Alaïa, Mulier saw the chance to rehabilitate his passion. “I didn’t see it as a fashion company,” he says. “I saw it as a house.”

When Mulier walked into Alaïa in 2021, the headquarters was still in a state of shock. The Rue de Moussy complex was not only a creative centre, it was the building in which Azzedine lived, worked, entertained and slept. Even today, the designer’s presence is felt in every crevice. I used to stay in one of its three immaculately spartan apartments during Paris Fashion Week and there was always a magic about the house: I was never invited to the designer’s legendary kitchen suppers, but I would listen to them, smoking in the courtyard, while being slobbered on by Wabo, the designer’s gargantuan St Bernard dog. “The company was a family,” says Mulier. “And when the father dies, there’s a loss of something big.” Richemont had waited three years after Alaïa’s death to call Mulier, “because they wanted to allow the house a moment of pure grief.”

Despite the trauma, however, Mulier was also aware the team “were hungry for something new”. He went in very humbly. “Honestly, I wasn’t even nervous. I didn’t even arrive with anyone. I didn’t come with an assistant, a stylist, nobody. I just worked with everyone.” The atelier he inherited was tiny: even now the design team can be counted on two hands. “At the beginning, they were all looking at me like I was crazy. But then they all got on board and, in truth, I learnt as much from them.”

Mulier was keen to not cast the house in aspic. He thought the skater had become a bit “doll-like” and needed a fresher look. He wanted to “simplify” the clothing and redefine the line. It all clicked when he “rediscovered the beauty of the first collections, which praised the lines of the body, and were so cleverly done”. Mulier drew on the first six years of the archive to find his creative pulse. His mission: “To find a new sensuality and lose the silhouette that we all know.”

Of course, when one thinks about Alaïa, one thinks of female curves. Thankfully, under Mulier, there’s been no deviation from that path. In the studio, he says, “I’m mostly thinking about the hourglass, and how when you make the waist smaller, everything becomes more round. Every time I work with the atelier it’s about the bombshell – the proportion between the breasts, the waist and the hips. It all comes back to that for them.”

His first collection, shown in summer 2021, put the bombshell centre stage; he also reintroduced the hood. He embraced an unapologetic glamour, with snake-like silhouettes and huge expansive skirts. Later collections have included jeans, “branded” with distinctive stitching that flatters the bottom and creates the illusion of a longer leg. He has also designed the world’s most gorgeous peacoat, re-established the “body” as a core product, and launched a swimwear range. Neither has he jettisoned the basics. The skater dress is still intact, only now with tweaked proportions including a slightly lower waist. “The skater skirt is like the Hermès Birkin, but it had come to represent a ‘bourgeois’ theme,” he says. “We still do it because it still sells,” he adds, “but I don’t think that’s what Alaïa is.”

The reaction to his collections has been positive, from critics, buyers and fans alike. “I love what Pieter does at Alaïa because it’s original,” says Alexander Fury, an HTSI contributor and one of Azzedine’s most ardent fans. “With a back-catalogue like Azzedine’s it would be so easy to rehash and rely on archives, but Pieter is instead creating something genuinely brave and new.”

“Pieter has brilliantly protected the Alaïa house codes while moving the collection forward,” agrees Alison Loehnis, president of Net-a-Porter, Mr Porter and The Outnet, and interim CEO of Yoox Net-a-Porter. “The bodycon dresses and playful yet cool accessories have all been incredibly successful. And his introduction of new categories such as denim reflect how he’s thinking about the customer’s full wardrobe beyond occasion and evening.”

The studio has also reignited Mulier’s love of fashion. “I always loved it,” he insists, “but it’s good to take a little break.” Right now he’s obsessing over leather: “It was only when I started here that I realised how amazing it is as a material for ready-to-wear.” He’s in awe of the design team: impressive, considering he’s worked among the best. “Azzedine was a great teacher,” he continues. “They still think like him when they create.”

After working for a mass-consumer label such as Calvin Klein, Mulier was anxious that he would not have to produce “merch”. He was adamant that he would not make the kind of streetwear that has become the backbone of so many brands. Nevertheless, he’s happy to acknowledge that his Alaïa has a sports appeal. Likewise with the logo: while he would be loath to use one without good reason, at Alaïa it’s a natural fit. “Azzedine did a logo T-shirt in 1991, so it would be quite on brand,” he shrugs. “But I don’t think it’s what will drive our company further.” Brand visibility is a far more subtle game. He points to the brand’s bestselling bag, Le Coeur. “Sure, it has a little logo on the front. But the interesting thing about that bag is that, from afar, you see a shape.”

Shoes and bags have been important drivers in a brand that still does 60 per cent of its business through ready-to-wear. The diamanté-studded Ballerina, for example, has become a sell-out – a great example of the brand’s organic marketing approach. Says Mulier: “We launched the Ballerina two years ago, but in the past six months it’s been selling like crazy, everywhere. How can you know in six weeks what sells and what doesn’t? Or if there’s a potential in a product? It takes much longer. We give our product a lot of time.”

Ultimately, he would “love to do lingerie,” and dreams of doing menswear. But, for now, he’s focused on making sure the fits are more inclusive and that they stay focused on delivering the core.

“Alaïa will always be Alaïa,” says Serrano, “but we have a strong potential to further develop the Alaïa universe. We’ll keep growing the ready-to-wear thanks to strong product pillars.” She also cites other categories to develop: “Custom jewellery, fragrance, eyewear…”

So far the results have been encouraging: Serrano says the company has seen double-digit growth. Mulier’s influence is working. “This year has seen the highest turnover in the history of the maison.”

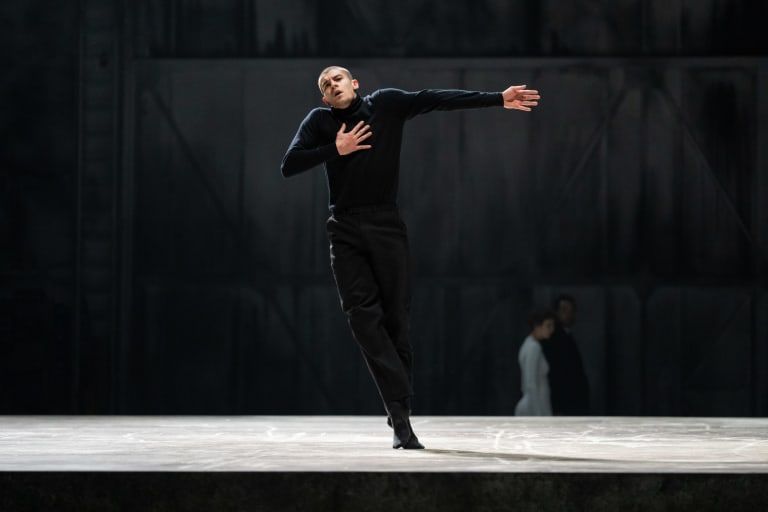

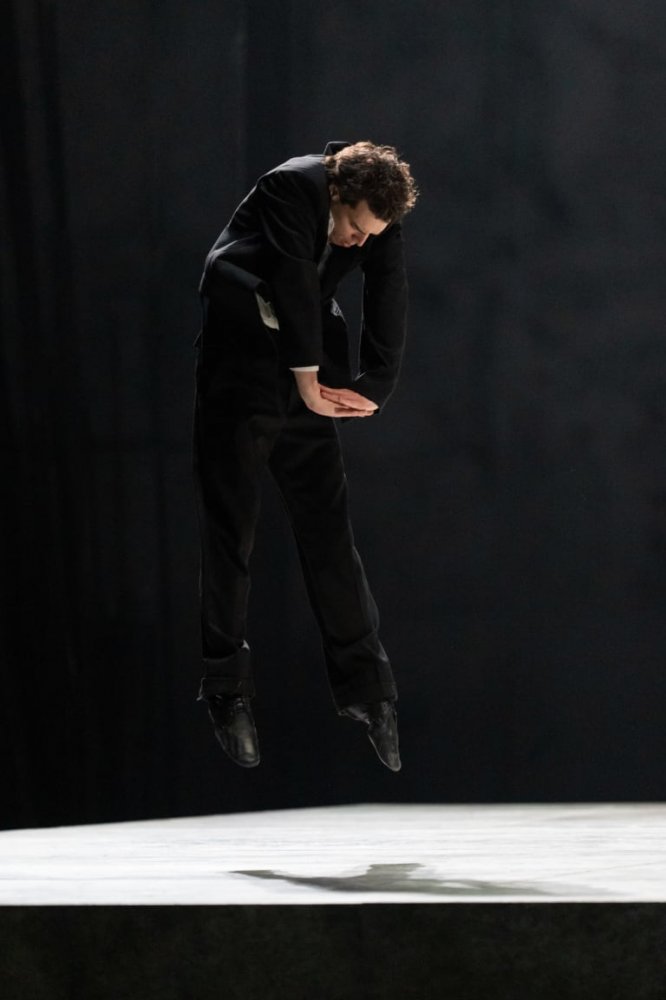

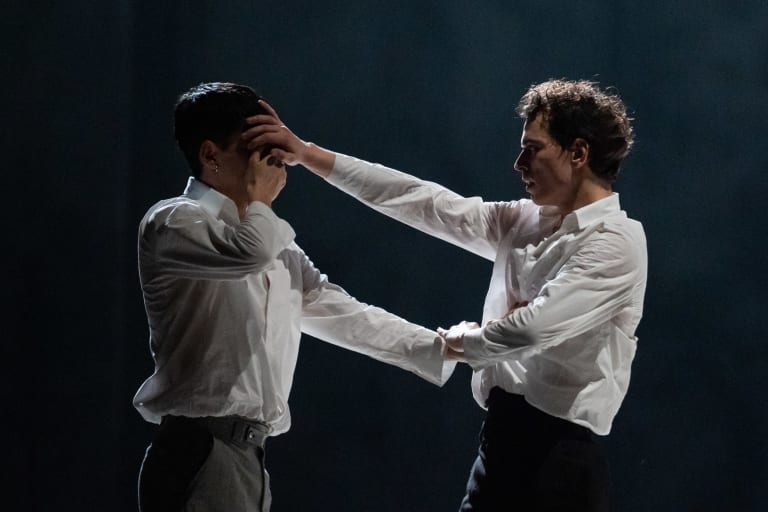

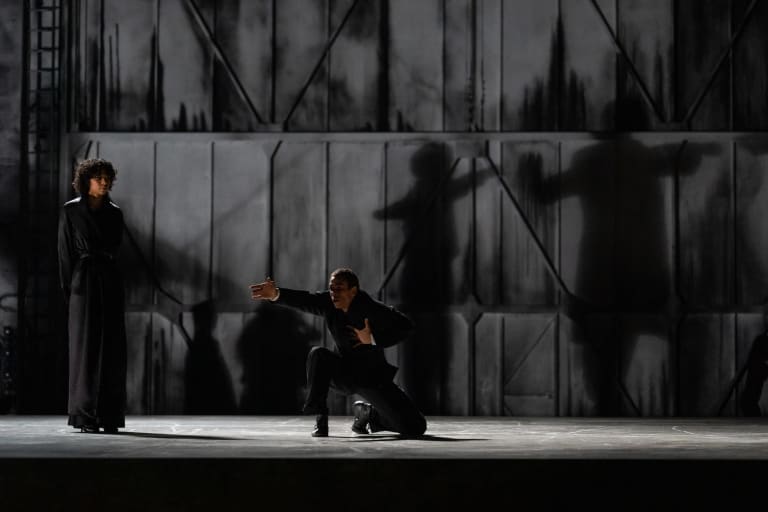

Mulier did not want to be a public figure, and, at Alaïa, he can still crouch in the shadow of its charismatic former head. But with each season he’s becoming more comfortable in the spotlight. It’s been quite the evolution for the former number two. In January, he staged the summer-fall 2023 collection at his home in Antwerp, the Riverside Tower, a brutalist apartment building designed by Léon Stynen and Paul De Meyer in which he has lived for seven years. Guests watched the show’s proceedings while crowded on his furniture, sitting in his kitchen, some even perching on his bed. “My therapist told me to do it,” he says of his decision. “Azzedine always showed in his house. And there’s something beautiful in showing it in this way, in opening the doors.” It was also a clever tactic in an era where people fly to ever-more exotic locales to see a show. “It was intimate, and therefore even more exclusive. It was luxury another way.”

It was also a moment for the designer to take pride in being Belgian, and to reevaluate “the importance of Antwerp, which we have all forgotten a bit”. Mulier has never identified as being “an Antwerp designer” – in the vein of Dries Van Noten, Ann Demeulemeester or Martin Margiela, who brought an intellectual rigour to fashion in the ’90s. But he is, nonetheless, a Belgian designer, who has always lived in Antwerp and returns there every week.

“I don’t like Paris that much,” he confesses. “I mean. I love Paris as a city. But as a community? I couldn’t live here full time. I have an apartment in Paris but it’s like a hotel room. It’s not my house.” Back in Antwerp, he’s “extremely normal – too normal”. He visits family (his sister, who works in real estate, and his brother, who’s a cook). He listens to the radio, walks the dog and cooks meals for friends. For 18 years his partner has been Matthieu Blazy, the Paris-born creative director of Bottega Veneta, whom he met while working for Raf Simons. The trio, now working for separate houses, have remained a tight clique in fashion. But Mulier will not further discuss his private life.

For someone at the heart of fashion, he has quite distinct and separate lives: Antwerp is for rest and relaxation. In Paris, he’s “here to work”.

What does his therapist think about that?

“She loves it,” says Mulier. “Well, she doesn’t love that I’m compartmentalising, but she understands that I need time for myself away from all of this. Before, I had a problem with work – I worked every single day, every weekend, every Sunday. I had to, and I loved it. But I worked too hard. Travelling to Antwerp gives me a reason to just leave it all behind.”

If I were Mulier’s analyst, I would say the past few years have marked a journey to the “self”. He has found independence, creative freedom and a clear distinctive voice. Alaïa has allowed him to focus on designing – he’s no longer required to buoy up the troops. He doesn’t have to court the influencer and, notwithstanding his Rihanna-at-the-Super-Bowl-2023 moment (in a red Alaïa puffer coat dress), he’s not seeking big-name clients. He’s fine with being exclusive. He wants Alaïa to be a brand you might discover on your own. “I don’t want to talk to everyone,” he says, of the industry’s preoccupation with talking to the broadest possible clientele.

Mulier has mixed feelings about the future of fashion, despite being an “optimist” at heart. The last collection he really loved was Loewe’s AW23 – for its “freshness” and how it allowed him to look at the clothes. “I sound like an old man now, but back in the days when we were with fashion people, we would talk about the aesthetic of brands. Now I have at least two or three dinners a week where I sit down and I hear people talking about money. This expression: ‘Oh, they’re doing well.’ OK, something is selling. But in the end, who cares? Fashion is in a strange state because the audience becomes so big that you want to talk to everybody and you don’t have a voice any more.”

At Alaïa, Mulier has found the perfect sanctum in which to focus on the clothes. He can fit, refit and refine his bombshell. He no longer needs to play the clown.