You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

1883-1971 Gabrielle "Coco" Chanel

- Thread starter oanadobre

- Start date

DosViolines

far from home...

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2005

- Messages

- 3,212

- Reaction score

- 12

DosViolines

far from home...

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2005

- Messages

- 3,212

- Reaction score

- 12

^^ Thanks so much for those!!She is timeless... I will never forgive myself for not making it up to the Met Exhibit in New York two summers ago...What was I thinking, I'd wait for the DVD to come out!!??

My pleasure.

If only I had the luxury to even consider the possibility of visiting a exhibition.

PS- You see so few Men In Hats signatures these days...!!!

Yes, 80s one hit wonders are a guilty pleasure of mine...

Now, to make this post a bit more relevant:

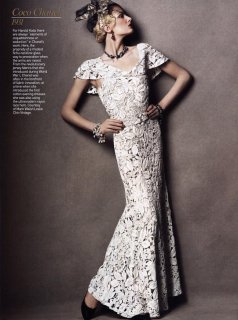

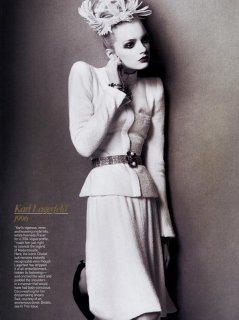

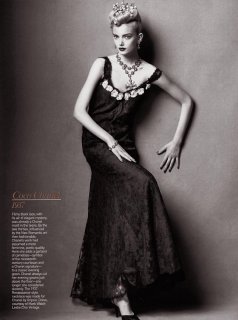

The Chanel Century

Hamish Bowles

Ph. Steven Meisel

US Vogue May 2005

bwgreyscaleHamish Bowles

Ph. Steven Meisel

US Vogue May 2005

I've included the Lagerfeld designs for the sake of consistency

Attachments

-

thechanelcentury_bwsm05.JPG186.7 KB · Views: 48

thechanelcentury_bwsm05.JPG186.7 KB · Views: 48 -

thechanelcentury_bwsm04.JPG129.2 KB · Views: 28

thechanelcentury_bwsm04.JPG129.2 KB · Views: 28 -

thechanelcentury_bwsm03.JPG170.9 KB · Views: 17

thechanelcentury_bwsm03.JPG170.9 KB · Views: 17 -

thechanelcentury_bwsm02.JPG110 KB · Views: 21

thechanelcentury_bwsm02.JPG110 KB · Views: 21 -

thechanelcentury_bwsm01.JPG98.3 KB · Views: 27

thechanelcentury_bwsm01.JPG98.3 KB · Views: 27 -

thechanelcentury_bwsm10.JPG137.1 KB · Views: 30

thechanelcentury_bwsm10.JPG137.1 KB · Views: 30 -

thechanelcentury_bwsm09.JPG109.7 KB · Views: 33

thechanelcentury_bwsm09.JPG109.7 KB · Views: 33 -

thechanelcentury_bwsm08.JPG84.5 KB · Views: 23

thechanelcentury_bwsm08.JPG84.5 KB · Views: 23 -

thechanelcentury_bwsm07.JPG77.4 KB · Views: 27

thechanelcentury_bwsm07.JPG77.4 KB · Views: 27 -

thechanelcentury_bwsm06.JPG174.9 KB · Views: 42

thechanelcentury_bwsm06.JPG174.9 KB · Views: 42

DosViolines

far from home...

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2005

- Messages

- 3,212

- Reaction score

- 12

sothebysMAN RAY

1890-1976

SUZY SOLIDOR WEARING CHANEL BRACELETS

1932

Attachments

DosViolines

far from home...

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2005

- Messages

- 3,212

- Reaction score

- 12

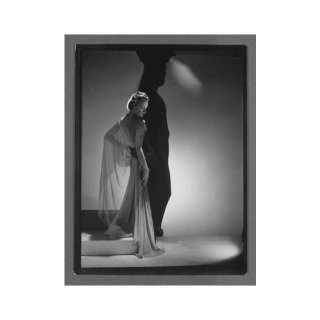

sothebysHorst P. Horst

CHANEL FASHION WITH SHADOW OF ERECTHION CARYATID, CIRCA 1936

Attachments

DosViolines

far from home...

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2005

- Messages

- 3,212

- Reaction score

- 12

sothebysEDWARD STEICHEN (1879 - 1973)

`MARION MOREHOUSE IN A CHANEL GOWN'

1925 (Steichen's Legacy, pl. 96)

Attachments

DosViolines

far from home...

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2005

- Messages

- 3,212

- Reaction score

- 12

artsjournal.comGabrielle Chanel: Evening dress, black silk velvet and black silk chiffon, 1932-33; Museum of the City of New York, gift of Mrs. Harrison Williams

Attachments

DosViolines

far from home...

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2005

- Messages

- 3,212

- Reaction score

- 12

telegraph.co.uk

Coco Chanel - la dame aux camélias

Last Updated: 12:01am BST 29/07/2007

The little black dress, tweed suits, costume jewellery and red lipstick - we owe them all to Gabrielle 'Coco' Chanel. As a new book celebrates her signature style, Linda Grant assesses the legacy of fashion's very arch modernist

In the autumn of 2005 I attended the launch party for Justine Picardie's entrancing new book about the history of all the clothes she had ever worn, My Mother's Wedding Dress: the Life and Afterlife of Clothes. Picardie's mother had, far back in the 1960s, got married in a little black dress, now faithfully copied for her daughter to wear at the party. The launch was held at the Chanel store in Knightsbridge, and it was a tribute to the power of a single word - Chanel - that almost every woman in the room was wearing a little black dress. Black had just made a comeback, but for many of us it had simply never gone away. The LBD, so easy to wear, so versatile in its possible interpretations as fashions come and go, is probably the single most enduring style statement of the 20th century, already racing on into the 21st.

The moment you say the word Chanel a picture comes to mind: of a square, stoppered perfume bottle, a little suit, a white camellia. Coco Chanel, credited with being the person who invented modern clothes, stamped her adamant, distinctive personality on everything she touched. An addictive new book, Chanel: Collections and Creations, by Danièle Bott, explores five designs that changed the world and asks what it was about Chanel's visual statements that are so enduring and alluring. Students of fashion can identify Dior's New Look, Yves Saint Laurent's le Smoking, Schiaparelli's skeleton dress or Jean Paul Gaultier's conical bra, but such is the power of the Chanel brand that if you showed those two intertwined Cs to any woman in any city in the world she would recognise them at once.

For Chanel style, someone who has never shopped further upmarket than Marks & Spencer can still buy a bottle of No 5 at duty-free, or a black powder compact at the make-up department of John Lewis. A man I know, who has been wearing the same uniform of jeans and leather jacket since the 1960s, has as his one concession to fashion the Chanel Homme aftershave he has loyally stuck to for 30 years because he likes the simple classic lines of its packaging.

It's hard to underestimate how much Chanel style has changed us all. The black dress existed before Chanel turned her attention to it, but it was considered funereal and, in the years before the First World War, buried under bows, pleats, lace, bustles and leg-of-mutton sleeves. What Chanel meant was a dress that was minimalist, sophisticated, elegant, to be worn at any time of day. Reacting against the sumptuous designs of her immediate predecessor, Paul Poiret, she advocated what she called 'austere luxury', the essence of chic. Her revolutionary approach to design meant that the black dress could be worn as day, cocktail and evening wear. 'A woman dressed in black draws attention to herself, not her dress,' observes Bott.

The very first LBD, the Ford of dresses, she called it, referring to the Model T car built on a production line for the masses, was designed to be democratic; any woman could wear one. The original design shows a long-sleeved, slim-hipped dress, gathered low at the waist and reaching to just below the knee. Its only adornments are two pleated Vs dropping from the shoulders and rising from the hem, meeting in the middle to further create the illusion of slimness. You could step out in it today and no one would notice that you were wearing something designed more than 80 years ago. Chanel would develop this concept for the rest of her life, altering the fabrics, adding sequins or chiffon trains, but the underlying structure remained. A black dress, with dropped waist and schoolgirl white collars and cuffs, worn over leather footless tights from 2003 reveals how radical her thought was. 'A fashion that goes out of fashion overnight is a distraction, not a fashion,' she said.

Chanel launched her career at the height of modernism, in design, art, literature and music. By returning to the essential form, the movement showed radical simplicity. Modernism was the thinking woman's fashion statement, and derived its power from the idea that women were no longer to be wholly decorative. They could act, and needed clothes to wear while doing so. Chanel herself designed things not as playful allusions to what had gone before but to meet the demands of her own life and body. When Karl Lagerfeld arrived at Chanel in 1982, there seemed to be no more unlikely a designer to lead the house. A master of post-modernism, he was the opposite of everything Chanel stood for, yet his greatest triumph was the revival of the Chanel suit.

My mother, slim and only 5ft 2in, had a wardrobe full of good-quality high-street copies of the Chanel suit. She knew they were what suited her best and she hung on to them long after they went out of fashion. The Chanel suit dates from the reopening of the fashion house in 1954 (it had closed during the war), but it was Jackie Kennedy who made it famous. In jersey and tweed, with its collarless jacket and slim skirt, it was meant to be a kind of second skin. Worn with a quilted chain-handle bag, two-tone slingbacks and a camellia brooch, it was a look as simple and sophisticated as the little back dress, but less dressed-up. Chanel insisted that every suit had pockets into which a woman's hand could actually fit, the jacket hem was weighted to ensure it hung properly, and the only concession to embellishment was the gilt buttons embossed with lion's head, stars, the sun or double C.

Lagerfeld radically reinterpreted the suit, making it in pink tweed, fraying the hems and jacket edges (a trend that worked its way to the Per Una range at Marks & Spencer), and in the process turned it into one of the most celebrated comebacks in the history of fashion.

One thing Chanel was quite clear about was her dislike of the unadorned face: 'I don't understand how a woman can leave the house without fixing herself up a little - if only out of politeness,' she said. She regarded the lips as the primary weapons of seduction and insisted on painting them a deep vermillion. As far back as 1921 she made her first stick of colour, protected in wax paper, the precursor of the lipstick as we know it today. Next she made for herself a mother-of-pearl tube, then a push-up case in gunmetal grey. Pictures of her early cosmetics show the designs to be startling similar to today's. The No 5 bottle remains unchanged since the 1920s. The black boxes she used for her powder and eyeshadow go back as far as 1932, and were made from Bakelite, then being used in car manufacturing.

But Chanel did not entirely eschew adornment. She was an inveterate wearer of necklaces, and the lavish, even Byzantine luxury of her jewellery contrasted with the minimalist lines of her clothing. The spectacular Comète necklace of 1932 is a diamond star from which a cascade trail of 649 diamonds drapes itself round the shoulder, arching at the neck and ending at the base of the throat. It is interesting that Chanel, who adored the minimalist form, should have thrown pearls and gold chains all over her severe canvas. Bott offers some suggestions: in the 1930s Chanel had accepted a commission from the International Diamond Guild, which she took because she felt that, in times of economic depression, too much austerity was… depressing. Another possibility is that her lover, Paul Iribe, was a jewellery designer. But perhaps there is a more material consideration: before she was a major designer she was a courtesan, the lover of wealthy men such as the Duke of Westminster who, in the tradition of the times, rewarded her affections with gifts of diamonds.

Yet her originality would hit on one emblem, the camellia, which in her hands became a necklace, a watch, a hat, a chignon, a detail on a button, or just a silk flower pinned to a dress. There was something radically simple about its shape, what Bott calls 'its perfect, almost geometric roundness'. As far back as 1922 a stylised camellia is embroidered on a blouse. Every season it appears as a jewelled monogram on a toe or beaded outline on the heel of a Chanel shoe. Like the lotus in Buddhism, the camellia expressed for Chanel a shape with infinite possibilities. And so she goes on, the way she saw and thought affecting the lives of millions unborn when she first discarded what was known and set out on an adventure into the future.

Coco Chanel in trademark ropes of pearls in a 1935 Man Ray portrait

Chanel's beauty packaging remains much the same today as it was 80 years ago

A 1930s gold, sapphire and ruby bangle

CHANEL FILM NEWS from Vogue Paris -

French actress Marina Hands, who won the best actress award at this year's Césars ceremonies for her performance in Lady Chatterley -- the French equivalent of the Oscars -- has been cast by director William Friedkin as fashion figure Coco Chanel in his forthcoming Coco and Igor about the tempestuous affair between Chanel and composer Igor Stravinsky. Friedkin told an interviewer at the Cannes Film Festival that his film takes place in 1913, at the time that Stravinsky's ballet, "The Rite of Spring" opened as a catastrophic failure and Chanel's perfume, Chanel No. 5, had become an enormous success. Actress Audrey Tautou (The Da Vinci Code) is expected to star in another film about Chanel -- before she became famous.

Both very beautiful actresses, btw! Can't wait!!

French actress Marina Hands, who won the best actress award at this year's Césars ceremonies for her performance in Lady Chatterley -- the French equivalent of the Oscars -- has been cast by director William Friedkin as fashion figure Coco Chanel in his forthcoming Coco and Igor about the tempestuous affair between Chanel and composer Igor Stravinsky. Friedkin told an interviewer at the Cannes Film Festival that his film takes place in 1913, at the time that Stravinsky's ballet, "The Rite of Spring" opened as a catastrophic failure and Chanel's perfume, Chanel No. 5, had become an enormous success. Actress Audrey Tautou (The Da Vinci Code) is expected to star in another film about Chanel -- before she became famous.

Both very beautiful actresses, btw! Can't wait!!

Hey, Christmas is right around the corner!!

Chanel By The Book Luxury Slipcase: set of 3 on fashion, perfume and jewelry

August 2nd, 2007

Now this is one for the loaded, if you thought the [COLOR=red! important]Guccibook was expensive then you need to check out the [COLOR=red! important]Chanel[/color] Luxury Slipcase.[/color]

This set of 3 Chanel books is by luxury publisher Assouline; the company has done collaborations with Goyard and Coach in the past.

The Chanel by book includes 80 page books on fashion, perfume and [COLOR=red! important]jewelry[/color]which are in a quilted slipcase.

By the Luxury Slipcase for $550.00 on vivre

Chanel By The Book Luxury Slipcase: set of 3 on fashion, perfume and jewelry

August 2nd, 2007

Now this is one for the loaded, if you thought the [COLOR=red! important]Guccibook was expensive then you need to check out the [COLOR=red! important]Chanel[/color] Luxury Slipcase.[/color]

This set of 3 Chanel books is by luxury publisher Assouline; the company has done collaborations with Goyard and Coach in the past.

The Chanel by book includes 80 page books on fashion, perfume and [COLOR=red! important]jewelry[/color]which are in a quilted slipcase.

By the Luxury Slipcase for $550.00 on vivre

Last edited by a moderator:

StyleIsInUs

Member

- Joined

- Apr 24, 2005

- Messages

- 758

- Reaction score

- 0

whoa, that's a lot cash, but I'd love to get one ...

liberty33r1b

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Nov 9, 2003

- Messages

- 24,347

- Reaction score

- 787

Chanel Defile Collection 1959

just found this video!! enjoy

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sutlG32fnrU

just found this video!! enjoy

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sutlG32fnrU

Last edited by a moderator:

rangerrick14

Member

- Joined

- Dec 20, 2005

- Messages

- 624

- Reaction score

- 1

Now Why can't channel still be theat chic?

Guessgirl96

Active Member

- Joined

- Jul 2, 2005

- Messages

- 9,520

- Reaction score

- 0

I'm surprised that most of these pieces would work today. Not as a whole outfit, but you could easily work these into other outfits and not look dated.

KitschyFox

meow, meow.

- Joined

- Jun 30, 2007

- Messages

- 515

- Reaction score

- 1

This is so interesting to see in comparison to the shows of today.

DosViolines

far from home...

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2005

- Messages

- 3,212

- Reaction score

- 12

PARIS—Coco Chanel, 1964.

© Henri Cartier-Bresson / Magnum Photos

slate.com

Similar Threads

- Replies

- 354

- Views

- 148K

- Replies

- 80

- Views

- 13K

- Replies

- 218

- Views

- 44K

- Replies

- 18

- Views

- 5K

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)