Thanks so much, BrownEyes (Edie's eyes were brown!)... It simply fascinates me how people came to know Edie, and what she means to people today. I really don't know a thing about her trip abroad with Andy, but that would be a great question to ask at edienation. I think this is an interesting article! Interesting that it echoes some of your sentiments, BrownEyes...

http://www.newsday.com/entertainment/movies/ny-etedie0128,0,2644614.story?coll=ny-entertainment-bigpix

Warhol's worlds revisited: Edie's 15 minutes

'Factory Girl' is framework for portrait of Andy Warhol 'superstar' Edie Sedgwick

BY JOHN ANDERSON

Special to Newsday

January 28, 2007

She didn't hang out in Haight-Ashbury, wear love beads or protest at the Democratic convention. Her borders, if there were any, were not contiguous with those of Woodstock Nation. But she was emblematic of the 1960s as much as anyone, and the ripples of her tumultuous wake can still be felt today. Just ask Paris Hilton.

Edie Sedgwick -- blue-blooded heiress, Andy Warhol "superstar" and the subject of director George Hickenlooper's new film "Factory Girl," opening Friday -- was the eventual casualty of drug abuse. Her persona in the celebrated Warhol movies (he made hundreds of minimalist films during the '60s) ranged from gamine-like to appalling. But she was -- during one sparkling instant in the metamorphosis of American counterculture -- the Holly Golightly of the mid-'60s New York art scene, the muse/escort of pop artist Warhol himself and a phenomenon that came and went in a magnesium ignition of flashbulbs and manufactured glamour.

Not that Sedgwick wasn't glamorous.

"She was unspeakably beautiful," said celebrated art curator and preservationist Sam Green, who as director of the Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania organized Warhol's first solo show in the fall of 1965. "But what made everyone fall in love with her was, one, that she had this poor-little-rich-girl aura about her; the sense that she would be easily endangered. You wanted to protect her, because, two, little girls like that don't survive in the big city."

She didn't. Sedgwick died in 1971, after a period of rehabilitation, from what was determined to be an accidental barbiturate overdose. She was 28. Sedgwick might have fulfilled the James Dean-related catchphrase of "live fast, die young, and leave a good-looking corpse," had she not pursued a headlong descent into drug-induced degradation. She was, of course, hardly a special case, not in that epoch. "I'm one of the few left from that era," Green said. "The '60s were really hard on us."

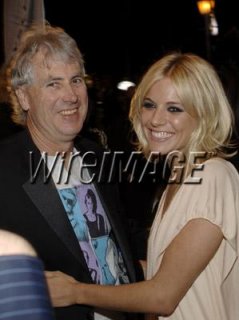

But in terms of creating a legend, Sedgwick's early death was not a bad career move. Born in 1943 in Santa Barbara, Calif., during a period when her dysfunctional family was living both there and in Cold Spring Harbor, she has resurfaced periodically as cultural icon -- notably in George Plimpton and Jean Stein's "Edie: American Girl" (1982), Melissa Painter and David Weisman's "Edie: Girl on Fire" (2006), and in the recent re-issue of the Warhol "screen tests." Now, in "Factory Girl," 21st century "it" girl Sienna Miller ("Casanova") plays the girl with the Colonial-era roots and the penchant for self-destruction.

"Charisma is the hardest quality to pin down," the actress said, adding that she spent a year researching Sedgwick's life, talking to people who knew her and gaining access to the archives of the Warhol Museum (in the artist's birthplace of Pittsburgh), where she viewed rarely seen Warhol films. Miller was trying to describe through performance a woman whose allure is often described as indescribable.

"She had limitless energy," the actress said. "You could see that in the films. I tried to emulate that. But there's a Rashomon quality to what happened in her life, thanks to what was going on back then. I was with a group of people from that era, including Edie's brother, Jonathan, who has become a close friend, and you'd have a conversation that began 'Remember that night ... ' and everyone's version would completely contradict the other's."

Still, Miller said she was smitten. "I would be happy to play her the rest of my life," she said.

The problem with that would be a shortage of material, even though the brief life Sedgwick led was filled with what might politely be called episodes. Even before she met Warhol, she had been twice admitted to psychiatric institutions; her family life, as stated in the film, involved child sexual abuse and a family line out of which mental illnesses popped up like inflatable pool toys. As the film portrays it, Warhol eventually betrayed and abandoned his waifish confidante, although there was at one time a bona fide friendship -- based on opposites attracting.

Into the Dumpster

"Warhol came from a fairly close family, Carpatho-Russian, from Slovakia," said art journalist and critic David D'Arcy. "In Pittsburgh, he was just another turnip-eating Eastern European. In New York, she represented good looks and lineage. Like [fellow Warhol superstar] Joe Dallessandro, she was a very presentable superstar. They looked great. A hell of a lot better than him . And he could go around with this good-looking entourage."

But once Sedgwick's drug abuse -- and, as the film portrays it, her relationship with Bob Dylan (called Billy Quinn in the movie and portrayed by Hayden Christensen) -- became uncomfortable for Warhol, their association went south. The icy way in which Warhol (Guy Pearce) maroons Edie in her drug addiction is reflected, many would say, in Warhol's art: the aestheticization of the banal, the bored representation of the boring or horrific, and the soup can as a joke on art buyers. It requires no stretch, regardless of Pearce's performance, to imagine the figurative amputation of Sedgwick from the corpus Warhol.

"He wore her like jewelry," D'Arcy said. "Once she was dead to him, she went into the metaphorical Dumpster that was parked outside the Factory."

Gerard Malanga, Warhol's assistant and co-founder, with him, of Interview magazine, said that both Warhol and Sedgwick knew what they were doing.

"Andy saw something in her that could advance his film career," Malanga said. "Edie was leading a sort of aimless existence and saw that he could help her. But there was genuine affection for each other as well."

Famous for being famous

In 1965, Sedgwick was the Herald-Tribune magazine's "Girl of the Year" -- a minor phenomenon that had begun a year earlier with a Tom Wolfe article on another eventual Warhol superstar, Baby Jane Holzer. "But when Edie's picture appeared in Vogue, posing on a leather, stuffed rhinoceros, it launched her into the public awareness," Malanga said.

It was, in many ways, the birth of the celebrity as celebrity, the concept of the famous person who is famous for being famous. Warhol's fabled 15 minutes of fame has since been blown into careers by the likes of Hilton, Nicole Richie, and most of the people who populate TV game shows. Sedgwick, whose story reads like a minor Greek tragedy, was among the first to achieve pop stardom simply because she was photogenic, telegenic and hungry for attention.

And as Hickenlooper's film so sadly tells it, when Sedgwick became a drug-abusing embarrassment, her so-called career fell away like a rusted suit of Gucci armor, or the dessicated bloom of a starved rose bush.

"She was a new face," Malanga said. "In those days the word 'celebrity' was not bandied about; the vocabulary was different. She had an innate talent, a glow, a personality."

And she represented something, pre-superstar, that was ripe for its time.

"In those days, and earlier, I guess, there was much more of what we would call snobbism in society," Malanga said. "She came from a very privileged, elite background, but she had the ability to break down barriers. She broke down that tradition she had grown up with. She had a very independent spirit and was very open, and likable."

And once she went back home to California, entered rehab, married and tried to escape the claws of what she and her visage had created, was she ever talked about at the Factory, by Warhol or anyone else?

"As far as I can remember, no," Malanga said. "Whatever we were involved in, it just went on."

Hooray!

Hooray! Hooray!

Hooray!

Fashion, art, music, film, literature are what I do for fun nowadays, my hobbies if you will. I study international law, human rights in particular, and while I find that super interesting too, fashion, art etc. are what inspire my creativity. I first read about Edie on the internet about three years ago, and the reason that I clicked to find out more about her was - if I remember correctly - her unusual name, and the link to Andy Warhol (the name is unusual to me at least, not being American). I think I then saw a picture of her here on this thread and was completely stunned

Fashion, art, music, film, literature are what I do for fun nowadays, my hobbies if you will. I study international law, human rights in particular, and while I find that super interesting too, fashion, art etc. are what inspire my creativity. I first read about Edie on the internet about three years ago, and the reason that I clicked to find out more about her was - if I remember correctly - her unusual name, and the link to Andy Warhol (the name is unusual to me at least, not being American). I think I then saw a picture of her here on this thread and was completely stunned

I love the 60's very much, the whole culture and aura from that time, both in America and other parts of the world. I love watching the films and listening to the music. Edie personifies that time in my mind, alongside other select few.

I love the 60's very much, the whole culture and aura from that time, both in America and other parts of the world. I love watching the films and listening to the music. Edie personifies that time in my mind, alongside other select few. what is important about Edie though is that it worked for her. I guess that is the appeal of her fashion sense: that she dressed in what suited her person, and always wore the clothes (and not the other way around) - which is something that will always be apparent and always appealing about anyone who manages to do that. I think the same can be said about Audrey Hepburn. it's difficult to explain, but I hope I've made some sense.

what is important about Edie though is that it worked for her. I guess that is the appeal of her fashion sense: that she dressed in what suited her person, and always wore the clothes (and not the other way around) - which is something that will always be apparent and always appealing about anyone who manages to do that. I think the same can be said about Audrey Hepburn. it's difficult to explain, but I hope I've made some sense.