Nymphaea

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Oct 30, 2012

- Messages

- 6,196

- Reaction score

- 695

John Galliano Opens Up

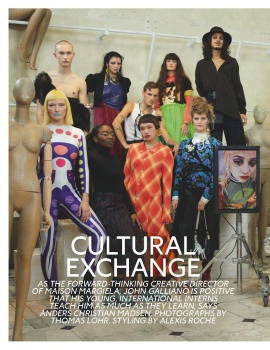

wsjAt Maison Margiela, the designer—one of fashion’s most virtuosic (and controversial) talents—is designing in the present tense.

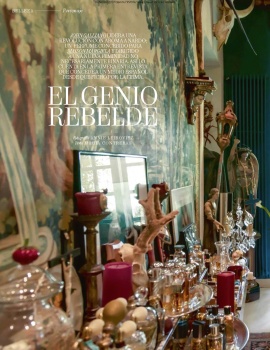

OPPOSITE AN orthopedics store and a scruffy bar in Paris’s 11th arrondissement sits an old convent building, its facade saturated with decades of grime. Across a cobbled courtyard lined with old latrines, a few flights up a stone staircase, is a rambling room decorated with antique eccentricities—from a vintage model ship to an articulated mannequin—like an attic of curiosities pilfered from Miss Havisham’s house. Into this room bounds a Brussels griffon, followed by a man wearing an odd assemblage of long trouser shorts, sneakers, a yellow T-shirt and a wool sweater slightly unraveling at the collar. “That’s Gypsy,” he announces. “She’s a recovery dog. I never had a dog before—it was just very good for me to be responsible and to not always think about myself.” He chuckles happily.

This is John Galliano, and he could not have chosen a more fitting place to hole up, if that is what he had intended to do. For the past three years, Galliano, 57, has been creative director at Maison Margiela, the fashion house founded in 1988 by avant-garde designer Martin Margiela, who elevated privacy to performance art: Only a few photographs of Margiela are known to exist, and he often veiled the faces of models in his runway presentations, or forwent humans altogether to show his clothes on stark clothes hangers. “Anonymity: A reaction against the ubiquitous star system, the desire to let the ideas do the talking,” reads an official Margiela “glossary” from 2009. In 2004, Maison Margiela took over this 18th-century building, whitewashing the crumbling interiors in keeping with the designer’s affinity for white, both for its cleansing properties and because it highlights imperfections. The space is just four miles but a world away from the primly perfect dove-gray hallways at the Avenue Montaigne headquarters of Dior, which Galliano helped build into a pulsing $1.1 billion empire—until he was fired days before the fall/winter 2012 show when a video of him drunkenly making anti-Semitic remarks at a Parisian bar became international news.

It would be easy to conceal oneself within Margiela’s cloistered heritage, but Galliano has nothing to hide. He says he has been sober for nearly seven years—he attended rehab after losing his post—and in that time has tried to face his demons head-on.

“I said what I said. I didn’t mean it,” he says now. “And I continue to atone. Some people have forgiven me, and some people will never forgive me. But that’s something that I have to take on board.” He says he is also still grappling with legal issues stemming from the incident.

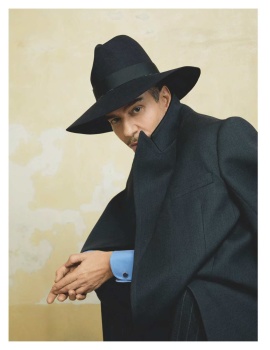

Before Galliano became a symbol of how the mighty can fall, he was a symbol of how the mighty had risen. Fashion, an industry that can sometimes seem as though it’s busy proving that nothing exceeds like excess, portrayed him as the apotheosis of romantic genius. He was appointed at Dior in the late ’90s, in an era when bold deal-makers like Dior’s owner Bernard Arnault, the architect of luxury conglomerate LVMH , had discovered there was a fortune to be made by applying the go-go strategy of M&A to the antiquated luxury world.

Galliano was the perfect creative partner, his Vesuvian imagination and virtuosic technical abilities unleashed by burgeoning budgets. He became the ultimate celebrity designer, paparazzi’d during nights out with supermodels like Kate Moss and Naomi Campbell, his long hair braided into plaits, his body buff and tanned. He delighted fashion editors with the imaginary tales behind his collections, told in a dizzying array of accents—jumping from the diction of a Shakespearean actor to “mockney” slang to his native Spanish to upper-crust French. He even supplanted his fabled predecessor, calling the line Christian Dior by John Galliano and taking runway bows as theatrical as his catwalk shows: dressed as a matador with pink stockings or a pompadoured astronaut or Napoleon. The French emperor, though, found Versailles too extravagant; not so Galliano, who staged Dior’s fall/winter 2007 haute couture show there in celebration of Dior’s 60th anniversary. Four years later, it was all gone: Galliano’s gilded fantasia vanished in a cloud of ignominy.

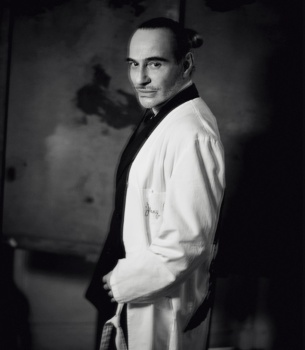

“I’m not God. But I realize that now,” says Galliano, who these days wears his dark hair pulled back by a simple black head wrap instead of the crown he once rakishly cocked for a photo shoot. “Whereas before I would self-will and self-will and self-will. When you are driven by perfection, you miss out on something beautiful that happens in between that is unfinished—that does have emotion that is relevant in this house,” he says, referring to Margiela’s appreciation for experimentation.

When owner Renzo Rosso first approached Galliano in 2013 to take over Maison Margiela—the founder had officially retired in 2009—Galliano’s response, he says, was “ ‘What?’ I didn’t get it at all.” (The Italian fashion impresario knew the designer from having manufactured the children’s line of Galliano’s eponymous brand.) He turned down the offer several times, but the persistent Rosso slowly seduced Galliano by taking him cruising through the Greek islands and the French Riviera on his motorized yacht, the Lady May. “I just loved the idea of working with this guy, the most important designer in the world,” says Rosso, who was unfazed by Galliano’s controversial history.

In 2013, he convinced Galliano to visit the Margiela headquarters when it was empty one Saturday night in August, and the building on rue Saint Maur finally won Galliano over. Upon entering, “I felt good—the beautiful decay, the peeling paint,” he says. “I had become so f—ing polished and so finished. Suddenly that rawness and emotion appealed to me, because I was feeling raw and emotional.”

Galliano immediately set about reorganizing the fashion house into the strict pyramidic structure he had mastered at Dior: a high-flying couture collection that garners attention and sets the tone for the ready-to-wear collections, in turn informing the commercial collections, the bags, the shoes and even the beauty lines. “It’s the only way I can work,” he says. “I was really honest [with Rosso]. I need to express myself—the parfum that can then be diluted into the eau de parfum, the eau de toilette.”

“John said to me, ‘I am a couturier,’ ” says Rosso. “I am very happy with that. A designer can just do a collection, but a couturier can dream and invent something that doesn’t exist.”

COUTURIER, God, that sounds grand,” says Galliano, laughing at himself. “I’m a dressmaker. There aren’t many of us who can cut, make patterns, drape.”

Galliano’s extraordinary skills have been his solace and his redemption: Just three months after he left Dior, he was slated to make Kate Moss’s wedding dress for her 2011 marriage to musician Jamie Hince. Without access to an atelier, he was left on his own to create the creamy confection, which featured a skirt of delicately embroidered feathers that appeared to have been dipped in gold sequins: “He sewed every sequin onto that dress himself,” says Condé Nast artistic director Anna Wintour. “People don’t make dresses the way that John does anymore.”

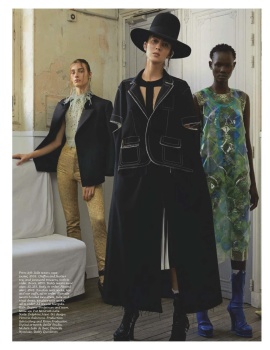

While Maison Margiela has shown haute couture since 2012—an offshoot of Margiela’s Artisanal project, through which recycled and vintage materials became one-off follies, such as leather sandals transformed into a lacy vest—it had become known primarily as an upscale contemporary line, serving reworked staples from the house repertoire. Galliano seized on the Artisanal idea, bringing gifted couture seamstresses to flesh out the Margiela atelier and installing longtime loyalists as his top deputies in the design studios. But how to apply Galliano’s taste for fantastical fairy-tale gowns to Margiela’s conceptualized versions of streetwise boots, sweaters and trench coats?

While Margiela was known for purposefully awkward elements such as the jutting, padded shoulders on his jackets and dresses, or massively oversize coats, Galliano had made his name with a liquid-like bias-cut gown, in which a single piece of fabric is sliced against the grain so that it wraps languidly around the body like a second skin. It’s dressmaking’s triple axel, enough to confound its cutter—and ruin yards of fabric—if not done with precision. But an early meeting with Martin Margiela, during which the designer said, “Take what you will from the DNA of the house, protect yourself and make it your own,” helped ease Galliano’s anxieties about melding their sensibilities.

“It’s exhilarating for me to be inspired by outerwear or a ski jacket. It’s not always a fabulous ’50s couture gown shot by Mr. [Irving] Penn,” adds Galliano, who was surprised to discover he and the reclusive Margiela shared an interest in 17th-century French literature and 18th-century costume. They also employed similar techniques, particularly early in their careers: “Bricolage, recycling, inside out, upside down—that’s kind of what you do when you are a young designer,” he says. “You destroy, you construct, you reveal.”

One of the ongoing motifs that emerged from this impulse is something Galliano calls décortiqué—the reduction of a garment to its inner skeleton, both a witty reference to Margiela heritage and a display of Galliano’s technical wizardry. Along with other themes (which he has given such names as “unconscious glamour” and “dressing in haste”), it appears throughout his couture and ready-to-wear collections as well as Avant-Premiere, which entails broader offerings. (Prices range from $184 for a T-shirt to $8,585 for a coat.) He has even turned out the bias cut in stiff tweed.

Deconstruction has been a preoccupation for Galliano from the beginning: His first Dior dress, famously made for Princess Diana’s attendance at the Met Ball after her divorce from Prince Charles in 1996, was a navy silk bias-cut slip, which Galliano constructed with an interior bustier to protect her royal modesty. But when Diana arrived at the gala to greet him and co-chair Liz Tilberis, “We were like, Oh, my God—she’s torn out the corset,” he remembers, leaving her décolletage scandalously exposed under the negligee-like lace straps, though the other guests—and, until now, Diana fashion historians—remained none the wiser about her last-minute alteration. “It was a reflection of how she was already feeling: liberated.”

Although Galliano himself seems to feel freed by his new home away from the spotlight, he is determined to remain respectful of Margiela’s legacy. He knows firsthand how sensitive it is to take on a living designer’s house, having lost his own eponymous line, which he had founded in 1988 (91 percent–owned by LVMH, it is currently designed by Galliano’s former right-hand, Bill Gaytten). “It was like losing one of your children,” he says. “A lot of work had to be done to stop me from doing anything silly.”

He pauses and looks away. “I was killing myself anyway—it was a slow death,” he continues. “I didn’t realize I was killing myself. I was completely in denial. You think you can deal with it and cope with it, and [you tell yourself] it’s just the creative pressures, and every excuse. The insidious disease that creeps up and takes you over, and I was too weak.”

“We all knew he was going through troubled times. And we tried to look after him,” says milliner Stephen Jones, a longtime collaborator and friend, who points out that for years Galliano was designing 15 collections annually, a rare feat in the industry. “He dealt with it extremely well for a very long time, and it became a huge success. But he was very much in the eye of the storm of fashion.”

The workload was notable to many. “He is such a perfectionist,” says Wintour. “He had the inability to delegate or let go. The job was almost too mammoth—it was the volume of work, and he was so particular about everything.”

“I was just afraid to say no to Mr. Arnault,” Galliano now admits. “I thought it was a sign of weakness and that I would lose my contract. How dumb. You know, when work becomes more important than your health—the work came first at the risk of everything. Health, relationships, family—ruthless. That’s how sick I was. And your world becomes the bottle, the drugs, the ups and the downs.”

He has been able to forgive himself by re-examining his life: the move to England from Gibraltar at age 6, growing up as a closeted homosexual in a strict Catholic family in South London, bullied at school until he found his way to St. Martin’s School of Art. “You see the little Juan Carlos Galliano-Guillen—what happened to him? That poor thing. And that’s where you start to be able to handle it. Because you become this—whatever I became.”

These days, he attends regular AA meetings and retreats four times a year to a wellness center in southern Spain following each fashion show. He’s home every night, he says, at his Marais apartment with longtime partner Alexis Roche, and spends weekends at their country house in Auvergne with their two dogs, pacing his workload according to a concept he calls “step by step.”

“Seriously, I just didn’t get that before,” he says. “Or living in the present—I didn’t understand. It took a long time to get that life is this, now, what we are doing, not my head stuck up my own *** thinking about 2020.” He also maintains a mostly macrobiotic diet, though his taste for cigarettes and coffee are unabated—as is his joyfully wicked laugh.

“Recovery is an amazing journey to go through—to be given a second chance at life, and to regenerate creatively,” he says. “I’m happy to talk about it, because I think it’s nice to hear that you don’t lose it all—that you can’t paint and you can’t write and you can’t sing, because it’s not true. You can. It’s actually more intense, the levels of creative highs. I guess it’s because you are more aware of them as well. Because you are just so electric—all the good things that I love about this industry, the process—oh! It makes me jump out of bed in the morning.”