Yohji Yamamoto, the wise warrior of fashion

By Sophie Abriat

For more than four decades, the Japanese fashion designer has continued to surprise with his radical creations. His austere and rebellious style appeals to a new generation of fans, including stars such as Offset, A$AP Rocky and Burna Boy. At 81, the tireless designer will unveil his new women's collection during Paris Fashion Week, on October 3.

Yohji Yamamoto did not disappoint. He appeared just as he does when he greets the audience at the end of his runway shows, true to his signature silhouette and dressed in black from head to toe: a felt hat with frayed edges, a dark shirt with rolled-up sleeves and a small buttoned waistcoat. Seated in an old club chair with worn leather, he scrutinized his interviewer with care. Then he gestured to sit down. "He is tired," his team warned us.

Between the jet lag, his being 81, and the preparations for his show that took place two days earlier, during Paris Men's Fashion Week in June, it was best not to "upset" or "rush" him. He spoke calmly and softly, taking his time to put into English what he wanted to say. When he did not want to answer a question, he politely said he had "no recollection," looking surprised, but with a hint of mischief in his eyes.

His Paris office looks like a hideaway beneath the eaves, perched like a nest above the stone nave of a former warehouse on Rue Saint-Martin, one of the oldest arteries in the capital, running through the 3rd and 4th arrondissements. The wooden beams are weathered with age, and the skylights let in the piercing light of that summer morning. A fan gently ruffled his salt-and-pepper hair. A cappuccino steamed to his right. To his left, his metal ashtray, which follows him from room to room. He has been smoking since he was 16, always ready to pull out his pack of Hi-Lite cigarettes.

Paris ritual

These few days spent far from Tokyo, where his workshop and the headquarters of the company he founded in 1972 are located, are always an intense time for the designer. Four times a year, during men's and women's fashion weeks, he follows the same routine, traveling to Paris with a small Japanese entourage. Even in October 2020, at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, he was one of the few who made the trip for his spring-summer 2021 collection. He came to take a bow wearing a mask, as the audience, moved to see him there when so many other fashion houses had chosen not to take part, applauded him.

He would not miss his trips to Paris for anything in the world, arriving with around 30 colleagues. The ritual ran like clockwork. First, they opened the trunk-wardrobes: Hundreds of pieces, transported by plane, were carefully unpacked and then hung on racks. After the model casting, Yamamoto finalized his styling (the composition of each look in the show) using his own unique method: The clothes were spread out on the floor in the order they would appear on the runway. He looked at them from above; that was how he best visualized the show.

Cigarette dangling from his lips, intensely focused, he swapped two jackets, added a piece of jewelry, removed some boots and adjusted the final details. In the room, silence was the rule; no one moved. Everyone watched for a gesture, an unspoken order, ready to spring into action to assist him. Unlike most fashion designers, Yamamoto never relies on a stylist to help him compose his vision. He remains the sole architect of his aesthetic, from the clothing itself to the overall look.

An anxious designer

Usually reluctant to deliver direct messages, he punctuated the pieces in his latest show (men's collection, spring-summer 2026) with explicit phrases: "Ocean disappears makes human finished," "Kill me softly," "Nuclear power disasters."

He said he was deeply worried about the state of the world, "the population is declining, especially in Japan." He also mentioned the "strange" temperatures, which, in fact, nearly reached 40°C on the day we met him, as a heat dome settled over the capital. "The living conditions are becoming quite terrible. The temperature is very strange, and we have too many wars on the Earth. I don't like it," he said wearily.

After 44 years of uninterrupted creation, hundreds of collections and runway shows that have gone down in fashion history, Yamamoto has stayed the course, continuing, as he always has, to create, invent and subvert forms and ideas. The designer, who describes his profession as a "duty," but also as a "sacrifice," works relentlessly: "I can't have a summer holiday, I can't have a winter holiday, that's impossible. No holidays. You can imagine four times the show in Paris. When I'm not working, I lie down on my bed and watch TV or listen to music." In the rare interviews he has given to the press, he repeated over and over that his time is not his own.

Allergic to mediocrity

His unclassifiable creations attract a new generation of fans. More and more of them are pushing open the doors of his boutiques in Asia and Europe, or scouring second-hand websites for enticing offers.

His work gained increased visibility a few years ago when he collaborated with sportswear brands such as Adidas (in 2002, as a pioneer, he created the Y-3 line in partnership with the German outfitter) and the skate label Supreme. The house now boasts 15 lines (including the Yohji Yamamoto men's and women's collections and the more affordable Y's line) that vary according to price range and target clientele.

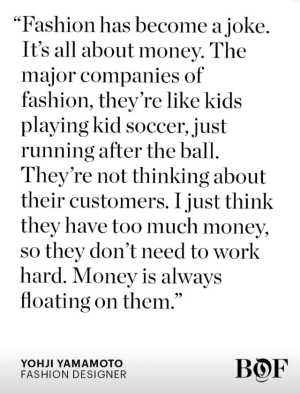

Today, the brand is thriving, with more than €200 million in annual revenue, 700 employees and 300 retail locations around the world. "It is currently experiencing a commercial revival," said his team, attributing this quiet but undeniable success to the designer's authenticity and integrity. On social media, several accounts (such as @myclothingarchive) have been sharing archival videos in which his words, reminiscent of an old sage, serve as mantras turned into Reels. "If you want to create something, keep resisting the mediocrity of ordinary things," he said in a 2016 interview for The Business of Fashion that is circulating on Instagram. "It is a life's work. Are you ready to sacrifice yourself to create something?"

Outside his fashion shows, a dense crowd, a tribe dressed all in black, proudly wears his clothes. Numerous celebrities, including American rappers Offset, Gunna and Rich the Kid, attended his shows. A$AP Rocky wears "Yohji," as does Nigerian singer Burna Boy. In March, backstage, Yamamoto posed alongside rapper J.I.D, both giving the camera the finger. There are no gifts, no appearance fees – no celebrities are paid to attend a presentation of the brand.

Talent magnet

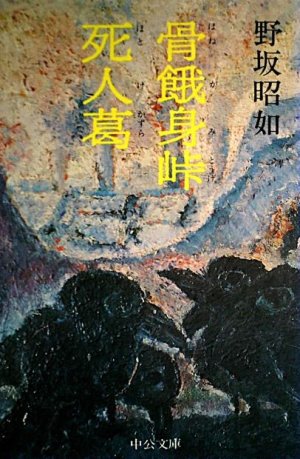

A fully-fledged artist, the couturier was also a painter – he excelled at charcoal portraits – and a musician (he composed the music for his own fashion shows and played guitar and harmonica in a band called Suicide City). He also wrote prose and poetry and published his autobiography, My Dear Bomb, in 2011.

"He is one of the rare fashion designers to be recognized by artists from other disciplines as one of their peers, able to engage in an equal dialogue. For example, he inspired filmmaker Wim Wenders, who dedicated a documentary to him [Notebook on Cities and Clothes], and he developed a genuine bond with choreographer Pina Bausch," explained French fashion historian and artistic director Olivier Saillard, director of the Fondation Alaïa. "His work is like a great book that one reads in silence: He does not need to shout to be heard. That is a great strength."

In January, Belgian artist Luc Tuymans, Scottish artist Robert Montgomery, French-Algerian photographer Mohamed Bourouissa and Paris Opera Ballet principal dancer Hugo Marchand walked the runway at his show, proof that the octogenarian still knows how to draw the leading talents of the moment to him.

"Every morning, I walk with my dog. After walking with my dog, I go to a bakery. People found me and approached me, and some of them asked me, can we take a photo together? Maybe I have become famous!" recounted Yamamoto, quickly adding, "I hate that! Only my outfits, only my fashion shows can be famous."

According to his friend Alan Bilzerian, founder of a multi-brand fashion boutique in Boston, Massachusetts, who has been selling his clothes since 1979, he did not say that out of vanity: "One day, we went to an exhibition in Belgium. When we arrived, so many people wanted to talk to him. But he went to lock himself in the bathroom, telling me: ‘Guard the door!' Whenever someone tried to get in, I told them to come back later. It was so funny!" Bilzerian added, "He's very introverted. He doesn't like to express too much with everybody. He's not for everybody. That's why he's so cool."

A criticized aesthetic

Yet Yamamoto did not always enjoy success. In 2009, his company went bankrupt and the designer had to start over from scratch, thanks to the support of an investment fund. Even his beginnings were tough. In 1981, he presented a collection in Paris for the first time. Models walked barefoot through the Cour Carrée du Louvre, dressed in deliberately distressed black clothes, sometimes even torn, as if they had already been worn. That set his work apart from the fashion of the time, which was divided between bourgeois elegance and the extravagance of designers like Montana or Mugler.

His show exploded like a shockwave. The press cried scandal. Some journalists referred to "funeral shrouds" and described his creations as "Hiroshima" or "Holocaust chic." His followers were nicknamed "the crows." His compatriot Rei Kawakubo – who had been his partner for several years in their youth and who created the Comme des Garçons brand in the 1970s – and he were labeled "the Japanese," a kind of foreign consortium come to challenge Western fashion. Their aesthetic was described as anti-fashion: hems were left raw, deconstruction and asymmetry reigned supreme.

While today oversized silhouettes and the blending of genres have become commonplace in collections, at the time, they caused a scandal. "It took me a long time to understand that what we, Westerners, consider beautiful and perfect, Yamamoto rejects. He has to come and disrupt all that, for example, by tearing the fabric," recalled a close collaborator.

Asymmetry is a key feature of his style. Often, one side of a jacket will slip out, a skirt will cascade down a single leg. "His asymmetrical designs, deconstructed silhouettes and unfinished hems are reflections of imperfect beauty, which is a component in the traditional philosophy of wabi-sabi, which values impermanence and imperfection," explained Yuniya Kawamura, professor of sociology at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York.

An angry son

"When I was young, after graduating high school, I was wondering if I should be a painter, if I should be a professional musician but I never imagined that I would become a fashion designer," said Yamamoto, who was born in 1943 in Tokyo, two years before the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and then Nagasaki.

For him, creation was not only a duty but also a way to purge his anger. His father, who was drafted into the army, was killed at the front at the end of World War II, when the designer was not yet two years old. He was one of the last victims of the conflict; his body was never found. His favorite camera, a Leica, was buried in his grave. As a child, his mother would regularly take him there to pay their respects. Yamamoto admitted he had no memories of his father. But he still feels a deep acrimony toward Japanese nationalism. "I am the only son of a war widow. I grew up with my mother. She worked very hard to raise me. After my father's death, she became a dressmaker. And me, I became totally anti-adult. I was very angry." This feeling of injustice, he said, did not fade over the years. Asked if he had ever forgiven his country, he replied. "No, not yet." Then he concluded: "If I hadn't become a fashion designer, I think I would have become a killer. I would have ended up in prison."

Mental strength

In Tokyo, at the end of elementary school, he enrolled in the private Gyōsei high school, run by French missionaries. His mother worked 16 hours a day at her sewing table to pay the substantial tuition fees. Later, the young man began studying law at Keiō, a prestigious private university. "I wanted to become a detective to catch the bad people. But I also wanted to be a strong man, a bad man myself."

Beneath his calm demeanor, Yamamoto has loved fighting since childhood. "I pretended to be a good boy, but, in reality, I was searching for somebody to fight with." His mother's combined shop and workshop was at the time located in the notorious Kabukicho district in Shinjuku, a neighborhood frequented by gangsters and prostitutes. He recounted that every day, the local thugs would team up to attack him. He wrote in his autobiography that he was almost always covered in bruises. Since he hated losing, he began practicing judo at the dojo in the Yodobashi police station.

Later, he developed a passion for martial arts and became a black belt in karate. Out of curiosity and to better understand his friend, Bilzerian also took up the martial art. "That's when I truly understood his mental strength. His mind and his movement are very combined. It's perfectly combined. He has a very strong mind and a very strong sense of control of his body. So it's a very good balance. I mean, that's why I think he's still working so hard."

The central role of his mother

Disappointed by his law studies and unwilling to follow the well-trodden path of a bourgeois life, the young Yamamoto dropped out of university and offered to help his mother in her workshop. She became angry and refused to speak to him for several weeks. "She finally agreed, as long as I went to a fashion school to learn the proper skills." To make sure the patternmakers wouldn't laugh at him, as she liked to say.

Over the years, Fumi Yamamoto became a central figure in the company. "A 'mama,' very sociable, extremely caring and she never left her son's side," recalled Nathalie Ours, who was the communications director for the house in France from 1992 to 2005. "During the fashion show seasons, she would come to Paris as well. For afternoon tea, she would prepare oshiruko, a red bean soup, for the whole team. And you had to eat it, or she would scold you!"

Her death two years ago at the age of 108 deeply affected the designer. "I wanted to give her, not a rich life, but a beautiful life, like that of a lady, while making her happy," he said. Yamamoto went on to enroll at Bunka Fashion College, the renowned Tokyo fashion school. He graduated in 1969, four years after Kenzō Takada (who died in 2020). Three years later, in Tokyo, he launched Y's, his first women's ready-to-wear line.

While working alongside his mother, he developed a distaste for the loud, floral style demanded by customers. For his own brand, he rejected color – "it hurts my eyes" – and embellishments. Black became his signature. In Japanese society, it is also frowned upon for widows to wear bright colors. It was from his mother, who always dressed strictly, that he inherited his taste for sobriety. His rejection of high heels also dated back to childhood. Marked by the sight of prostitutes walking the streets of the Kabukichō district, he often says in interviews, "They give you big calves, it's ugly."

Sometimes described as spiritual, brooding, joyful, mischievous or combative, the man who has a reputation for smoking, drinking and gambling seems straight out of a novel, capable of remaining silent for days on end. "He has his secret garden," confirmed Ours. "At the office, it's true that we often waited for him the way people wait for Godot." In 2010, Le Monde described him as follows: "A fan of the whisky-cigarette-sleeping pill cocktail, this self-proclaimed epicurean who dreams of owning nothing but a backpack likes to hang out in the underbelly of the city, go all in at mahjong and billiards, and show off behind the wheel of his 1950 convertible Rolls-Royce." And what about his seductive side? "Women? No, no women! My mother was everything to me. Every time I wanted to introduce a girl to her, she would say: 'What kind of monster do you want to show me this time?' We argued sometimes. When I passed the age my father was when he died, I shouted at her: 'Hey Mother, I'm older than your husband now!'"

A perfectionist

More than just an "artistic director," a term now used for fashion designers, Yamamoto is a couturier, excelling in the art of tailoring. In Tokyo, in his workshop located in the Shinagawa district, a business center bristling with skyscrapers, he personally perfects each garment. In the morning, he drives there by car (he lives about 20 minutes away), behind the wheel of an old Nissan that used to be a taxi. "He loves it, he finds it funny and mysterious. Yes, you see, it's a good summary, you know, of him," joked Bilzerian.

Fitting sessions remain highly ritualized, even if a few small things have changed almost imperceptibly. There was a time when his employees called him Sensei (a Japanese term meaning "master" or "teacher," used to address a figure of authority and respect), but now a simple Yohji-san ("Mr. Yohji") is enough, and sometimes shachō ("boss") slips out.

For two months, for each new collection, the ritual of fittings takes place once a week, on Fridays at 5 pm. In silence, the patternmakers present him with their muslin prototypes. If he wants to correct something, he will ask to see the pattern and make modifications on the floor with a pencil. Sometimes, he will grab a pair of scissors and cut directly into the fabric. He can spend two hours on a single outfit. "It's a sacred moment, during which he is very focused," recalled Ours. "He puts all his energy, his faith, his soul into a garment. Into every detail. And then there's this fabric that doesn't cling to the skin, that always lets a bit of air through."

While he has paid tribute to Madeleine Vionnet, Gabrielle Chanel and Azzedine Alaïa (who died in 2017), Yamamoto said he did not want to dwell on the past. "I hate archives. They kill creativity," he said. In the 1980s, he even burned his prototypes so as not to look back. "Often, ideas come to me when I'm driving off from my house to the company. So I quickly write them down. I believe it's my father's presence: I feel he's watching over me and sending me ideas. All I have to do is catch them."

Always on the edge

The weight of age has started to show: he no longer paints, saying, "It's too time-consuming." But he still makes music and lights up when the conversation turns to Bob Dylan: "One time, I asked him to walk for my men's show. He said no." In the fashion industry, he still moves along the edge, "on the dark side of the road." He has his admirers, but also his critics, who point to the length and slowness of his shows.

"His runway shows are divisive, yes: Some people get bored, others feel an incredible intensity. I always think there are clothes that are truly breathtaking. People used to say the same thing about Madame Grès: silent runway shows, almost repetitive, but the work itself was powerful and timeless. For Yamamoto, it's the same thing: His work should be judged over time, across all his creations," commented Saillard, who admitted he often rewatched Yamamoto's 1999 wedding-themed show on YouTube. "It's the last great runway show that gave me goosebumps," continued the fashion historian. "It had everything: performance, reflection on clothing, emotion. A moment of grace. The models came in dressed, then, over the course of the show, they gradually lost their clothes. It was a simple yet deeply moving piece of staging that has profoundly inspired my own performances."

For the past three years, his daughter, Limi Feu – herself a designer who showed under her own name in Paris from 2007 to 2012 – had been working with him "very hard and intelligently," Yamamoto explained, adding that he had "started to accept her creations." In March, eight of her pieces were included for the first time in her father's womenswear collection. Yamamoto, who said he believed in destiny, shared that he would be very happy to see her continue what he had started. "How many times have I thought about quitting? So many! Especially recently." But the work must go on. Paris awaited him for his womenswear show scheduled for 7 pm on Friday, October 3, in the slot between Givenchy and Victoria Beckham. He'll be there, as always.

Le Monde