Jil Sander Bathes in the Glow of Uniqlo

By SUZY MENKES

HAMBURG — Jil Sander leaps up from her desk, where a low shelf with a wood sculpture and framed drawings is the only decoration between parquet floor and the room’s white wedding-cake of a ceiling cornice.

“Look,” she says, tugging at her fitted white blouse, displaying its deep cuffs and pearly buttons. “39 euros! Real buttons — and a very nice cut.”

The blouse is part of what Ms. Sander’s calls “only a baby,” her collaboration since October with the Japanese company Uniqlo, which also made her small, body-curved navy blue jacket. Her pants came from her previous life at the Jil Sander label, where her style morphed over three decades from sleek severity to sweet serenity.

At 66, Ms. Sander is still exceptionally pretty, her hair in tender blond tendrils above eyes as Nordic blue as the local lake on this sunny day in Hamburg, her home territory.

When she was Heidemarie Jiline, she hated her mother taming the unruly curls into plaits. But she loved that her mother made pants, teaming them with home-made corduroy, button-down shirts, using the sewing machine that Ms. Sander took over when she set up her own label fashion company in 1968, at age 24.

“I was very early in liking trousers,” says the designer, who noted that her female school teacher in the postwar years disapproved of this revolutionary sartorial statement but “when I came in a dress she was always smiling.”

To say that Ms. Sander knows her own mind is to state the absolutely obvious. This sensitive yet strong woman, trained as a textile expert, created a fashion house, overcame the flop of a Paris show in 1975 and listed her company on the Frankfurt stock exchange at the end of the 1980s, when her purist vision was a counterculture to the prevailing glitz. The fact that she walked out twice on Prada — in 2000 and again in 2004 — after the Italian company had taken a 75 percent stake in Jil Sander, is part of 21st-century fashion legend.

But she does not want to talk about that — the word “Prada” only falling once, like a hard pellet, in a two-hour conversation. She attributes the fallout to the changing corporate fashion world. And her preferred subject is +J, as her new venture with Uniqlo is called.

She bathes in the glow of Uniqlo, which has brought her fashion redemption — and maybe sparked a revolution. For instead of replicating her earlier upscale output, she has become the first high-level designer to devote her entire skills and energy to affordable fashion.

With its clout and wide production network in China, Uniqlo, part of the ¥1.42 trillion, or about $15.34 billion, Fast Retailing group, listed on the Tokyo stock exchange, has managed with +J to make a fashion line that still has close attention to detail. Ms. Sander’s friends no longer ask, as they used to: “Why are your clothes so expensive?”

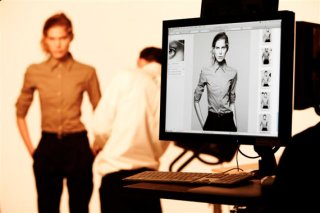

Joe McKenna, the stylist who worked with the photographer David Sims on the Jil Sander campaigns and again for +J, says that nothing has changed in Ms. Sander’s approach to her new role.

“It’s that same exactness, the same discipline — every thread and every button is as important as it was at Jil,” says Mr. McKenna, who has witnessed three or four fittings for one low-price Uniqlo garment.

Ms. Sander is exultant about the new autumn/winter collection that will go on sale in September: a shapely ginger coat with pockets curving over the hips; or a stylish cornflower blue parka teamed with a blue coat — both set to retail at under €120, or $150. The summer collection, currently in selected Uniqlo stores, tells the price story for both the men’s and women’s lines: a parka with detailed pockets and cords sells at €49.90; a three-pocket tailored jacket at €79.90.

“I give it all my passion and all my experience — it is a little adventure,” says Ms. Sander. “And maybe it is destiny that I am doing it for more people — I feel it is a little bit like a present.”

The designer says that she hates the word “cheap” and is putting all her focus on functionality and consistency, with the clean silhouettes and meticulous details that stamp her style.

“My mother always said that we were too poor to buy too cheap,” says the designer, referring back to her childhood days in a “broken” Hamburg, ruined by the wartime bombing. Looking outward, like so many in this port city, she escaped to Los Angeles, studying at UCLA, moved on to New York as a magazine fashion writer, but came back, at age 21, to join her younger and older siblings after their father died unexpectedly at 52.

Ms. Sander now has expensive tastes: modern works from artists including Silvia Bächli, Imi Knoebel, Cy Twombly and Andy Warhol are displayed, as if in a gallery, in the white stucco building here that was once the Jil Sander showroom. Like her stores, the space was beautifully re-proportioned by the New York architect Michael Gabellini.

And then there is her home, the chalk-and-cheese mansion next door, with its rich red dining room, decorated with an ironic take on Renaissance still life paintings; ornate, gilded wall carvings, re-housed from a private Venetian theater; and grass-green velvet chairs where a window gives on to the formal garden.

This house was designed by the late Renzo Mongiardino, whose style could be described as the polar opposite of Mies van der Rohe’s concept of “Less is more.” Yet the Italian architect is Ms. Sander’s hero, his noble bearded face in a framed photograph in the library.

The antique books — and maybe the baroque effects — show the influence of Ms. Sander’s partner Dickie Mommsen, whose taste is literary and musical. Ms. Mommsen defines pleasure for her as attending a Daniel Barenboim concert when she visits her children in Berlin.

There is also Ms. Mommsen’s house in the country, north of Hamburg, where the couple share a passion for planning and tending a garden that sweeps down to the Baltic sea.

In those wilderness years, after the second walkout, when Ms. Sander traveled as never before, lingering in Africa, she bought a holiday house on a whim, another residence on a bracelet of homes that already stretched from Paris to Berlin.

But even if her personal life is more about accumulation than her minimal design aesthetic would suggest, the strong will of the designer was evident from the outset. She describes herself as “always on a mission even when I was quite young. I was always very interested, very visual.”

Jean-Jacques Picart, the French consultant who worked on the poorly-received first Jil Sander Paris collection shown at the Plaza Athénée hotel, remembers that collection as: “fluidity and simplicity, cashmere jersey, silk and second-skin fabrics, a focus on knitwear and big coats — and young model Inès de la Fressange in a boyish pants suit.”

To Ms. Sander, the show was a devastating failure, assuaged only when she opened her trademark minimalist store on Avenue Montaigne nearly two decades later in 1993.

“She was much too early — it was something so different in the era of Mugler, Montana and Ungaro,” says Mr. Picart, referring to the fashion giants in the late 1970s.

Ms. Sander herself rejects the word “minimalist,” so closely associated with her plain clothes in precious fabrics.

“I prefer to call it ‘pure’ — minimal can be very empty,” says the designer, who gave the name “Pure” to her fragrance back in 1980.

Her collections have always had an emotional resonance, revealed backstage, when her hands shook as she stroked the fabrics and explained their significance.

It might be supposed that Uniqlo and Tadashi Yanai, the chairman and chief executive of Fast Retailing, threw the bereft designer a lifeline. She admits that “it was very difficult for me — the company was my home” and that “it’s like a boarding school — you are never alone.” After the bust-up with Prada, she used yoga and exercise to heal herself. She never mentions the word “depression” and her friends remain silent about this period, one saying “she has been hurt enough.”

“I learned early how deep and difficult fashion can be,” says Ms. Sander, talking about German character in contrast to American “can do” or extrovert Latin attitudes, saying: “we go deep and find problems.”

The designer now seems happy, energized and even a little amazed at how well the Uniqlo collection has worked out as a “good basic product” with “the right quality and the right proportions.” She exhibits an innocent wonder that the Chinese factories (which she has not yet visited) can interpret her vision for so little.

“In the end, this choice came almost accidentally and I slowly started,” says Ms. Sander, explaining that “somebody called me from Uniqlo” and then it was a “step by step process” in a country that was closed for a long time and where the “hierarchy is very difficult” and where even emancipated women “have to be girls, sweet and pretty.”

Currently there are trips to Tokyo almost every month, but Ms. Sander hopes that she can develop the former Jil Sander showroom and her in-town office as a Hamburg hub, in order to cut down on travel.

The rest of her time is taken up with the country garden, with its “rooms” laid out, in the manner of England’s Sissinghurst, by the British landscape gardener Penelope Hobhouse. Even here, the designer shows her strong-will, according to Ms. Mommsen, demanding implacably that a tree must be moved to fit with her vision.

Then there are her partner’s grandchildren — the girls as feminine as Ms. Sander never was, with one of them, aged nine, hankering after red high heels .

“Can you imagine — me!,” says the designer, whose footwear of choice is a pair of black leather buckled boots.

“But I believe a woman is always strong, even when she plays girly,” says Ms. Sander.

Then she frowns and asks, swooping her arms up and down: “Why is it always going in cycles — with all this glitz, those Italian television presenters and ‘Sex and the City’? You can be sexy, cool and intelligent.”

Yet there is no rage in her words, as there might have been in the feminist era that she helped to define in fashion terms. Ms. Sander is at ease, although she says that she must feel good in what she wears or otherwise “I feel weak somehow.”

Her mother died last year — a peaceful passing with all the family gathered round.

“When your mother goes with you up to 93, you think it is forever — I feel blessed,” says Ms. Sander. “I remember when I became 40, I understood my mother much better. And the last section, when I stopped working, I could kiss her all the time. It was fortunate to become so close.”

Her mother always dressed in Jil Sander. (“I think she was quite proud,” says her daughter.)

In April, Ms. Sander signed up with Uniqlo for another three years — which will bring her to age 70.

“I don’t feel my age — I am so active , very playful and also very childish,” she says. “The most important thing is to work on the spirit, to feel like a feather — lighter and lighter.”

nytimes