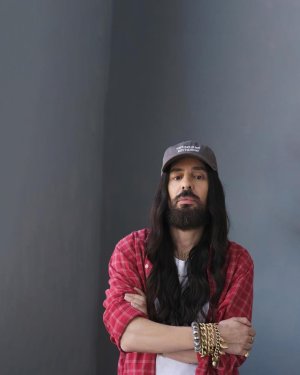

Alessandro Michele And Emanuele Coccia Get Philosophical About Fashion: “Clothes Aren’t Only Artefacts, They’re Hallways To A Different Reality”

BY

TIZIANA CARDINI

5 June 2024

Whoever thinks that philosophers are shabby dressers with no sense of style, and that fashion designers are egotistical illiterates only worried about the length of hems, better think again. Emanuele Coccia, the academic sensation whose bold thinking has made philosophy sexy, and

Alessandro Michele, whose equally provocative practice has invigorated the discourse around gender well beyond fashion, are both telling examples of how inaccurate such assumptions are. Coccia’s style is as flamboyant as his speculative musings, while Michele has an erudite, esoteric way with words. In a sort of twinning radicality, they have partnered in the writing of a book,

The Life of Forms – Theory of the Re-enchantment. Published by HarperCollins (for now only in Italian, with an English translation coming next autumn), it’s a deep dive into the unexpectedly magical liaison between philosophy and fashion.

The book was presented by the authors at Milan’s Teatro Franco Parenti to a full house last Friday, marking the first public appearance by Michele since he left Gucci in 2022. Conceived and written during the lockdown, the tome is a cogitation on the principles that have underpinned the designer’s influential praxis. The absence of images or photographs is conspicuous: “While the book has become a reflection about fashion along the way, ultimately it’s about so many other things,” Michele said. Divided into seven stanzas (philosophy, ambiguity, animism, design, collections, Hollywood, twins), the book is structured as a philosophical conversation, with sections “recalling the Talmud or the Bible.” It’s capped off by a final part reprising the scholarly press notes Michele wrote with his partner Giovanni Attili for the 22 shows he staged during his tenure at Gucci, from 2015 to 2022.

While we await for

Alessandro’s much anticipated debut at Valentino in September, I met with the two savants (a sort of two-headed hydra with considerable intellectual bandwidth – a rather intimidating task, really). Our conversation touched on clothes as a sort of portal to different dimensions, why words and good writing matter, and, yes, what Michele is making of his new place of business.

How did this book come about?

How did this book come about?

Emanuele Coccia: It happened quite naturally after Alessandro and I were introduced by his partner Giovanni Attili. We immediately connected, we recognised ourselves in each other’s words. I have taught history of fashion [Coccia is a professor at Paris’s EHESS, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales], and fashion is a sort of obsession for me. Alessandro is the first designer whose shows were accompanied by short philosophical texts, underlining the possibility for fashion to be actually narrated through philosophy. The book’s content is somehow consequential to how he has approached his fashion shows. I believe that fashion is the art that allows life to take its form, and therefore is the privileged subject of philosophy.

Alessandro Michele: As Emanuele said, there was never a planned project for the book. It just happened. The book hasn’t been conceived as a sort of remedy for today’s state of fashion; nor was it meant to be written as a treatise to explain how fashion and clothes are of the essence to tell us how alive we are. It has been dictated by a peaceful urge to give voice to a common passion, a conversation we wanted to have. For me, it has been a gift in the path I’m going through. And because it was written during the lockdown, it was also a company, a way of reflecting on the meaning of things. I wasn’t working at that time, work had taken a distance from me. In the book, we’ve tried to explain the reasons why I do things the way I do, a rather mysterious thing to analyse.

Philosophy and fashion are two disciplines that have never truly acknowledged each other, as they seem to be entities with quite opposite raisons d’être.

AM: I’m not a philosopher, so I’m in a rather privileged position in that it gives me more freedom to be curious. I’ve never studied it in school, I’ve come across it growing up, through life, and I’ve found it close to the practice and language of psychoanalysis. It’s an extraordinary medium: transparent, airy, oxygenating, a pair of glasses to see the world more clearly. And I’ve seen my work through it in a sharper way. Philosophy is perfectly suited to adhere to everything that’s human. For me, it has been a state of grace to discover a way to narrate something so mysterious but at the same time so easy, as philosophy can unravel knots, it can liberate narratives on the intensity of life. Fashion has often been marginalised, so I make philosophy and fashion go hand in hand. Like children, they seem to be best friends. I’ve never seen two things so perfect for each other, they seem to be the missing part of one another.

In the book you say that “philosophy seems to be naturally attracted by fashion,” which actually seems rather counterintuitive.

EC: Alessandro’s gesture of explaining his shows via philosophical press notes has been historically rather meaningful, as if he were saying: Look, to read fashion we have to overturn the idea of hostility or dislike between fashion and thought. Alessandro often says that clothes are the form through which you manifest your being alive. When we think, we’re trying to give shape to our being alive. For centuries the so-called Minor Arts – and fashion has been always considered one of them – have been marginalised. Today, designers and couturiers seem to have embraced the concept that making clothes is actually a form of culture – not only

haute couture but

haute culture.

The book is actually a dense discourse on fashion, with pensées such as “There’s nothing more free than fashion”, and “Fashion is the most radical art form of our time,” just to quote two. Can you expand on that?

AM: Fashion is radical, because it happens quickly and sharply. Everything else takes lengthy processes to happen and manifest; fashion is reactive. When we want to say something strong and immediate, fashion is the most potent of languages, and it reaches and touches everyone. It can build walls, it opens up conversations, moves emotions and thoughts; it can also be dangerous, socially subversive. Fashion has changed the idea of, “Who am I?”, and it has somehow changed art as well. There’s this misconception about clothes, because they’re merch, they’re sold and bought, while the body is considered purer. So art has worked with the body and not with clothes, because clothes are dangerous, they convey so many messages; fashion can be uncomfortable and it has to stay well confined in its corner. This is just the confirmation of how potent fashion can be. Fashion is extremely seductive: It’s like an addiction, it’s so alive, it belongs to anyone. It’s so close to our skin, it cannot be separated from the wearer.

EC: Fashion is universal, we can think of lives that never touch on art, or poetry, or painting, but everyone has to be clothed, regardless of geography, social status or gender. Art releases a distant gratification, a contemplative enjoyment, you’re in front of an artwork that makes you keep a distance; paradoxically and

au contraire, fashion is as if you were in front of a Picasso and you decide to put it on yourself, and this is not an ostentatious act, rather it’s performative, it’s something transformative. Fashion gives people enormous freedom; when they say that fashion activates conformism, it’s just a silly assumption, because if fashion is commercial and full of zillions of sellable options, then it’s only you who have the power to decide what to buy, what to wear in the morning, and this act opens up an abyss of freedom, that sometimes can be also utterly distressing. For me, the most telling example of the freedom fashion gives you is the fitting room; you can desire and choose a beautiful outfit that in the end doesn’t suit you at all, it’s like a door that slams on you. Through clothes we’ve come to understand that we cannot be only what our anatomy has dictated, and this is fashion’s greatest promise of freedom. Clothes can give us a sort of additional body, and fashion is probably the only art form suggesting that our only way is transformation. You cannot avoid speaking out through what you’re wearing.

Alessandro, you’ve often said that we’re the Frankensteins of our lives.

AM: Clothes aren’t only artefacts, rather they’re doors, vessels, hallways that lead us to a different reality: denser, richer, more ambiguous than we could inhabit if they weren’t there. Sometimes your life changes because you encounter certain clothes by chance. I like the idea of the hallway because it isn’t a room, but rather a passage, a path that you don’t know where it leads. It’s that specific dress that makes decisions together with you and makes you discover things you didn’t know existed. As Emanuele said, art is also a way to walk that hallway, but there’s always a distance that clothes do not allow to happen. Art and fashion today seem to be closer, but I’m not interested when art pervades fashion preposterously; it seems a sort of act of desperation to me. I like when the language of fashion is rotund, when clothes narrate their own language in a potent way, while using art as a sort of “higher” justification seems like putting fashion in intensive care.

John Waters once said, “If you go home with somebody and they don’t have books, don’t f*ck them.” Yet books today seem not to be on the cool radar, especially books on fashion, even if fashion is a universal language where opinions seem to be substitutes for critique.

EC: Fashion has existed and manifested through multiple media – shows, exhibitions, photography and also words – but before Alessandro, I must say that press notes in general were like bad photographs of the collections they were describing. The language of fashion has been reduced to something rather flat and banal. The work of a visual artist, Anselm Kiefer or Philippe Parreno, for example, could never be described as “light,” “soft,” “fresh,” “youthful”… perhaps it’s also because big fashion brands have helped culture stay separate from fashion, financing art foundations where fashion is never exhibited. If you think about it, it’s a way of saying that ultimately fashion is just business.

AM: The use of words in fashion has been kept within the perimeters culture has allowed fashion to inhabit. I’m happy that people today talk and write about fashion, even when there are mannerisms or distortions… it’s good to open the window and let in some fresh air, some oxygen. Today, fashion has become a free animal again, even if they’re trying to shut the doors and this moment is foggy and rather dark. There are banks of fog out there.

Speaking about fogs and hallways, you’ve just entered Valentino’s hallway, which seems to be much more fabulous than foggy, is it not?

AM: It’s a state of grace! Archives seem places where the past is frozen, but not at Valentino – they’re full of life. Perhaps I’m a sort of dowser, I seem to have the ability to make things speak, so I’m in great company there. There’s no hint of dusty melancholy or nostalgia of the past, it’s a hyper-vital place – walking through it I feel blessed by the Gods, it’s like having got your hands on a treasure, a treasure of life. That place is life itself. And Valentino means a name, an actual person who has narrated his life through beautiful clothes, everything he did he did through the clothes he created. Clothes were his language, and what he did it’s so potent that it’s still a place full of presences and voices. I’m in its present now; I’m watching and almost spying, like a voyeur. The place is alive, and talking, full of gorgeous objects and clothes that still seem to be inhabited by the bodies who wore them, and when you meet them it’s like meeting the women for which they’ve been created. It’s heaven on earth. An extraordinary experience. It’s like I have found the Eldorado.