I saw on Linda Evangelista's Instagram a screenshot of her conversation with someone who appears to be a person who went to the MET. According to that person, apparently, no one even recognised Rei when she went to the event as they were busy taking selfies and posing in front of paparazzi...quite shocking if you ask me but at the same time, I cannot say I am surprised... this event has turned into some kind of a puppet show of publicity victims... Therefore, it is not surprising that people just ignore the theme all together...

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

MET Costume Institute Exhibition 2017 : Rei Kawakubo/Comme des Garçons

- Thread starter Deleted member 116819

- Start date

^^^ If only the show was really at some abandoned Walmart in upstate New York— or realistically, Kmart, since that chain is closing at the speed that Comme churns out all these diffusion labels… Like when Comme started these pop-up shops in the Japanese suburbs.

People are too obediently attached to names and always want to defend the ones that they admire when they may feel there’s an attack: Whether it’s Alaia, Yves, Rei... Lemaire’s mainline menswear’s coats is awesome and a couple of them from the A/W 2017 will be mine this fall, but his offerings for the men’s Uniqlo is beyond dull dull dull. So I really don’t care that it’s the MET and Comme— I’d be tempted to climb up there as well and bring those pieces down to eye-level. I want to see the details and textures. Throwing those designs up there all comes off as we-ran-out-of-spots-for-these-so-let’s just-stack-them-up-there-like-deadstock.

I'm not attached to Uniqlo and besides this is about interiors not product. I simply do my research before making some careless comment. And as far as this thread goes, I don't see anyone obediently attached to Rei's or anyone's name or someone being too defensive, so I don't understand the rationale behind going off on that tangent.

The only valid criticism will be coming from those who actually go to the Met to see the exhibition for themselves. A criticism of three-dimensional space via two-dimensional pictures of that space does not make sense to me. Maybe if there were a movie of the exhibition space floating around somewhere.

Last edited by a moderator:

MulletProof

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Apr 18, 2004

- Messages

- 28,899

- Reaction score

- 7,979

^ same can be said about shows really... most things translate completely differently in real life but I would argue that it's actually easier to have some accuracy in criticism when it's static like this, unlike pictures of say, ballet. In fact, I've noticed (personal observation with little value) that sometimes the opportunity to access something not everyone has the chance to see (such as a performance, an exhibition in a specific city) can also work the other way around, as in the high of exclusivity blocking the way for whatever qualifies as valid... people don't emit criticism based on clear-as-day, unbiased visuals they're confronted with, but once it's all been processed through all of their social baggage (perceptions of status, sense of achievement, the importance this has in whatever circle or field they're in, self-importance.. and can I add academic performance lol).. and you see the poorly valid results of this in fashion probably more magnified than in any other field, attendance/first-hand experience rarely resulting in negative criticism and frequently in some nirvana-type of standing ovation.

By no means am I saying not seeing it is more accurate than seeing it btw .. just got a little dense wondering about the good ol' argument of physical experience giving automatic validity in judgement, when it's hardly the case. I'm curious about the new Institute of Arab Art opening there and in this particular case I do feel the internet is hiding things from me, so hey I might as well take that obnoxious coast-to-coast flight and redo my thoughts on this..

.. just got a little dense wondering about the good ol' argument of physical experience giving automatic validity in judgement, when it's hardly the case. I'm curious about the new Institute of Arab Art opening there and in this particular case I do feel the internet is hiding things from me, so hey I might as well take that obnoxious coast-to-coast flight and redo my thoughts on this..

(sorry about the spelling, typing on phone+ESL).

By no means am I saying not seeing it is more accurate than seeing it btw

.. just got a little dense wondering about the good ol' argument of physical experience giving automatic validity in judgement, when it's hardly the case. I'm curious about the new Institute of Arab Art opening there and in this particular case I do feel the internet is hiding things from me, so hey I might as well take that obnoxious coast-to-coast flight and redo my thoughts on this..

.. just got a little dense wondering about the good ol' argument of physical experience giving automatic validity in judgement, when it's hardly the case. I'm curious about the new Institute of Arab Art opening there and in this particular case I do feel the internet is hiding things from me, so hey I might as well take that obnoxious coast-to-coast flight and redo my thoughts on this.. (sorry about the spelling, typing on phone+ESL).

Phuel

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Feb 18, 2010

- Messages

- 6,291

- Reaction score

- 11,446

I didn’t mean to give the impression I was on the slightest of tangents, Uemarasan. Sorry if you took it as such. (I hate emojis and never use them when posting, so if yourself, or anyone got the impression I’m deadly serious with my posts— I’m never LOL)

And as far as the only valid criticisms are from people that have been at the show? Wow… Maybe you're joking... Once again, my comments are on a fashion forum, and not anywhere near intended as a professional criticism. I go with my first impressions and definitely don’t research in depth before making a post. I guess if we’re to go by your rules of what qualities as a valid post, then only those that have/had attended fashion shows can comment on their impression of the shows??? This place would be a ghost town if that were the case LOL

(Mullet put it to post better than I could ever dream to— as she always has… ESL and all…)

And as far as the only valid criticisms are from people that have been at the show? Wow… Maybe you're joking... Once again, my comments are on a fashion forum, and not anywhere near intended as a professional criticism. I go with my first impressions and definitely don’t research in depth before making a post. I guess if we’re to go by your rules of what qualities as a valid post, then only those that have/had attended fashion shows can comment on their impression of the shows??? This place would be a ghost town if that were the case LOL

(Mullet put it to post better than I could ever dream to— as she always has… ESL and all…)

YohjiAddict

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- May 26, 2016

- Messages

- 3,660

- Reaction score

- 5,216

runner

.

- Joined

- Feb 26, 2004

- Messages

- 12,918

- Reaction score

- 1,585

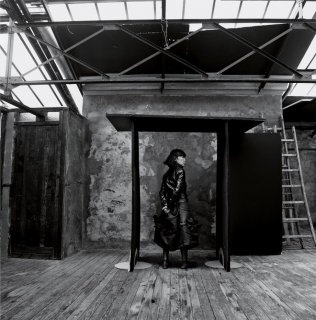

On a rain-soaked March afternoon in Paris, in a former nineteenth-century ballroom in the Eighteenth Arrondissement, Rei Kawakubo, the founder of Comme des Garçons, is staging her fall 2017 show. A slow procession of young women, their arms often bound to their bodies, giving them the look of dressmaker dummies, are swaddled in bulbous, undulating layers, rendered in what could be insulation material or tinfoil or a substance reminiscent of a brown paper bag. On their heads are wigs of coiled silver curls that were inspired, the master hairstylist Julien d’Ys says, by a sponge he found at the supermarket. On their feet is the one concession to practicality—the trainers that Comme has designed for Nike.

At the end of the show Anna Cleveland emerges, dressed in a black-and-white confection that recalls a giant melting wedding cake, and does a little twirly dance, like a broken music-box doll. Since 2013, Kawakubo has ditched the conventional catwalk in favor of this kind of avant-garde parade. Closer perhaps to performance art than fashion show, these living sculptures elicit a wide range of emotions—from wild applause, even tears, to bewilderment bordering on annoyance.

Eight weeks after this show, Comme des Garçons will be the subject of “Rei Kawakubo/Comme des Garçons: Art of the In-Between,” the Metropolitan Museum of Art Costume Institute’s spring 2017 exhibition—only the second such show to honor a living designer, the other recipient being Yves Saint Laurent in 1983.

Kawakubo is undeniably influential, a cult figure in the industry, but her designs are far from Saint Laurent’s easy trenches and sexy smokings. When she burst on the scene—her first Paris show was in 1981—she shocked the fashion world with her droopy, dark silhouettes, her reliance on plebeian fabrics like black polyester, her radical abandonment of the conventional notions of attractiveness. Unglamorous her garments may have been, but they immediately caught the eye of artists and outliers at odds with the big shoulders and disco dramatics that ruled runways in the eighties. In the decades that followed, Kawakubo expanded her repertoire, exploring the relationship of the body to clothing in ways both raw and uncompromising. From the beginning of her career, she has been stunningly audacious. If we now accept unfinished hems, asymmetry, a palette of unrelenting black, and overblown and deconstructed silhouettes as just another part of fashion’s lexicon, we can thank Kawakubo for pursuing this innovation with ferocious conviction.

“I really think her influence is so huge, but sometimes it’s subtle. It’s not about copying her; it’s the purity of her vision,” Andrew Bolton, the curator in charge of the Costume Institute, tells me over tea in the Salon Proust at the Ritz. The exquisite room, with its book-lined walls and cozy elegance, is a profoundly different setting than the upcoming exhibition—which Bolton says will be an austere, all-white maze hosting approximately 150 Comme ensembles. “Rei was really involved in the design of the exhibit,” he says.

As visitors travel through this labyrinth, they will encounter examples from collections including the house’s renowned spring 2005 Ballerina Motorbike show, which combined tutus and leather jackets (and which Kawakubo described as “Harley-Davidson loves Margot Fonteyn”). If the Ballerina Biker has a butch prettiness, other designs are far more challenging: 1997’s reviled Body Meets Dress—Dress Meets Body, colloquially known as the “lumps and bumps” collection, featured stretch nylon clothing distorted with asymmetrical padding, resulting in a swelling effect that many fashion critics compared to tumors.

I do not own a lumpy-bumpy dress, but I do possess a great many examples of Kawakubo’s work. I have been enamored of Comme des Garçons from the first time I saw it, at the original Barneys on Seventeenth Street, more than 30 years ago. It was a navy wool schoolgirl smock that stole my heart, and it cost $260—at a time when I was earning $135 a week. I told a credit union that my refrigerator broke, got the money, and bought the dress. I thought it would change my life, and it did. Over the years, so many other Comme garments and shows have spoken to me—the 2006 masculine/feminine Persona collection, the 2012 2-D Paper Doll coats. These clothes, by uprooting conventional notions of fashion, of beauty, helped me find my own way to shine.

At 7:45 a.m. the day after the show, I arrive at the Comme headquarters on the Place Vendôme. I have an interview scheduled with Kawakubo later in the morning, but I am allowed to sit in on an early session during which the notoriously taciturn designer will be taking an audience of employees through last night’s collection. After a screening of a video of the show, watched in reverent silence, Kawakubo takes the stage. With her husband, Adrian Joffe—also the president of CDG and Dover Street Market—serving as translator, she tells the audience the collection is about “the future of the silhouettes,” “a way of expressing the notion of un-fabric,” and also that “the commercial collection is mostly using un-fabric.” Those three thoughts constitute the entire presentation.

Joffe, South African by birth and ten years Kawakubo’s junior, joined the company in 1987. He and Kawakubo married in 1992, at the Paris City Hall. It is a partnership with its own rhythms—while Joffe is based in Paris, his wife lives in Tokyo, in the upscale Aoyama neighborhood, walking distance to CDG’s flagship. (Kawakubo is reportedly the first one in the office in the morning and the last to leave at night.) When you see them together, he seems to serve as her protector—not just translating for her, but also shielding her from inquiries deemed too prying.

Only at Comme could the un-fabric clothes that hang in the showroom be considered a “commercial collection”—skirts sport stiff tubular growths; jackets are faced with a shiny silver substance that looks like Mylar and turns out to be vaporized aluminum and polyester film. Still, though these pieces may be highly eccentric, they are not upholstery cocoons—they can leave the catwalk and take to the streets. “Collection is Rei’s ‘creation,’ and the commercial collection is her ‘style,’ ” an employee tells me, and I am reminded of the political adage that one campaigns in poetry and governs in prose. Thierry Dreyfus, who is responsible for the lighting for Kawakubo’s shows, tells me something oddly similar: “I think Rei’s work is poetry,” he says. “It is like when you read Whitman—you participate, and then you share something; but nothing is said, nothing that can be explained.”

Poetry it may be, but one should not underestimate the prose component—in the decades since the label was founded in 1969 (early designs bear a striking resemblance to Sonia Rykiel), CDG has expanded to include 130 or so stores all over the world selling not just the main label but subsidiary lower-priced lines, including the Play merchandise, with its heart-face trademark, and limited-edition collaborations with companies from Hermès to Speedo.

Kawakubo never went to fashion school—she says she got a job at a big fiber company, purely by chance, and the whole thing happened by accident. And while that may be true, it also serves as another example of the mists that envelop this brand. In addition to her own work, Kawakubo’s atelier has developed and promoted a roster of designers that include Junya Watanabe, Kei Ninomiya, and Chitose Abe, who worked at CDG before starting Sacai. In 2004, Kawakubo and Joffe opened the first Dover Street Market in London, and there are now five branches. DSM could be described as a sort of hipster department store featuring a mix of world-class brands—Alaïa! Balenciaga! Gucci!—and an assortment of tiny labels Kawakubo and her team have discovered. (She is always on the prowl—last spring, she was spotted at nightlife impresario Ladyfag’s Pop Souk in the East Village, a showcase for the kinds of fashion kids who whip up their samples in Bed-Stuy bedsits.)

At exactly 10:30 a.m., I am sitting across from Kawakubo to discuss poetry, prose, and her upcoming exhibition. Half hidden behind a Mac laptop, she is disarmingly tiny, wrenlike, clad in a miniature leather biker jacket and a long plaid skirt—her uniform. If I am nervous, she is even more skittish. (This shared shyness is nothing new: Many years ago, when Comme launched its first perfume, there was a party for her at Barneys. Everyone was having fun, except for two people standing timidly in opposite corners, looking down at the floor—Kawakubo and me.)

I arrive with the knowledge that many have faltered on the shoals of the Comme interview—and that talk of the intersection of art and fashion leads to one-word answers—so I decide to try a different tack. “What makes you laugh?” I ask. The reply: Nothing. When I ask her if the success of the brand and her legendary status has surprised her, she replies that she is not doing anything special: “I am just working day-to-day with what I believe . . . just dealing with my work—just like everybody else.” (Joffe is translating her remarks for me, though Kawakubo seems to understand English and listens intently when I speak to her, nodding and sometimes even offering a semblance of a smile.)

Well, OK, I say, but surely ordinary people aren’t having Met exhibitions? “It’s a halfway thing. It’s like something on the road to something—it’s not a final thing. There’s no guarantee. . . . Maybe after the Met I won’t be able to make anything? Maybe the company will go down; I’m not sure.”

She asks if I understand what she is driving at, and I decide to tell a story about how Jane Fonda once asked her dad, Henry, why he took every dumb role that came his way even after he was a Hollywood legend, and how Henry replied that maybe he would never get another chance to act. Kawakubo loves this.

She warms up a bit, sharing that she enjoys the films of Steve McQueen (the director, not the late actor and race-car enthusiast.) She likes London because there are lots of trees. She doesn’t particularly care for Paris, but she felt that it was the international center for fashion and wanted to be there when she stopped showing in Japan. She thinks New York is all about work.

To lighten the mood further, I ask her what she is going to wear to the Met, and she shakes her head and says she’s not going. “Yes, you are going!” Joffe tells her. “You don’t have to stand on the red carpet, but you have to go to the dinner!” In that case, she says, she will wear what she is wearing now—what she wears every day.

I gingerly approach the subject of the exhibition itself, and she declares that while she never wanted to do a retrospective, she has made some compromises. “It’s a Met show for Comme des Garçons, not a Comme des Garçons show at the Met,” she says. Like many artists, she is deeply uncomfortable with the thought of another pair of hands, another set of eyes arranging and interpreting her work, even if those hands and eyes belong to Bolton, who has an intense appreciation and respect for her creations.

Speaking with her, you cannot help but get a sense of her intensity, her solitude—and, in truth, a profound sadness. Since she is loath to acknowledge her success, I ask her what she considers her biggest failure. “Maybe the fact that it’s such hard work to do what I do and so much torture and living in hell and getting so tired working dawn to midnight every day for the last 40 years—maybe that would be called a failure in some sense,” she replies. When people insist they are blown away by something she has done, she doesn’t believe them. After all, she says, no one has ever come backstage after a show and said, “This is not as good as last time.”

But sometimes people truly are blown away by outsize imagination, sheer nerve, an artist’s crazy vision! Kawakubo may eschew this whole notion of art-as-fashion, but Bolton is sure that her originality, her stunning creativity, will enrapture visitors. “I know we will get people who will laugh at it and not see the intention—the ones who reduce fashion to wearability,” he says. “But I hope most people will be inspired by it.”

And Bolton has his own version of my refrigerator story, though his involves not a schoolgirl smock but a sweater from the fall 1982 collection, a pullover full of holes. He was obsessed with finding this rare item for the exhibition, and finally, at the last second, one turned up. Known as “the Lace Sweater,” it will be proudly on display somewhere in the maze, and you will also be able to buy a version in the exhibition store—a perfect blending of art and commerce, a salute, in all its bohemian grandeur, to a brand and a woman whose ornery, uncompromising creations have transcended the mere categories of fashion and art.

text above: Lynn Yaeger

photos below: Annie Leibovitz

from vogue.com

then one must expect the beautiful truly to attain its "proper" quality only in another sort of departure from itself - into the sublime. that is, the beautiful becomes the beautiful only beyond itself.....

- jean-luc nancy / the sublime offering

Attachments

Last edited by a moderator:

Not Plain Jane

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Mar 3, 2010

- Messages

- 15,479

- Reaction score

- 844

did anyone buy the book the MET is selling? should i? is it good value? worth having? is there much text? any help / opinions you can offer are very welcome, thanks!

YohjiAddict

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- May 26, 2016

- Messages

- 3,660

- Reaction score

- 5,216

did anyone buy the book the MET is selling? should i? is it good value? worth having? is there much text? any help / opinions you can offer are very welcome, thanks!

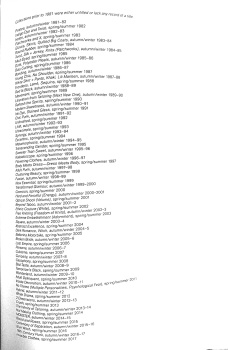

I just finished reading it and I cannot recommend it enough. It’s such an intelligently designed book from the content to the layout, furthermore it’s a very lush edition and at that price is a steal. As you must already know the exhibit and book is built around a series of dichotomies that serve as a framework for the clothes. The curatorial approach is explained by Bolton on an introductory essay but the rest of the book is composed by quotes from Rei. These quotes are so wisely chosen that chapter by chapter you come to understand not only the way in which the collections came to be but her thoughts on beauty, design, fantasy and so on and so forth.

The photos alone would justify the purchase; Most of them are really beautiful. The books starts by documenting the first few collections she showed in Paris during the eighties, they are illustrated by plenty of archive pictures by Lindbergh and a couple by Hans Feurer. The pictures commissioned for the book are kind of out of the box when it comes to an exhibition catalogue, you can see how each photographer was given free reign to give their own point of view. A photographer that surprised me was Ari Marcopoulos who doesn’t usually work in fashion but really does justice to both collections he was given to shoot. Inez & Vinoodh and Paolo Roversi were the ones I liked the most because they photographed each collection under a different setup and they really took great care with each image. Some archive photos of Paolo are included. I was surprised by how much I liked Collier Schorr’s pictures . I was a bit underwhelmed by McDean. The only photographers that stick to the typical format of a fashion catalogue are Brigitte Niedermair and Nicolas Alan Cope.

The last seven collections are the ones that are explored in more detail; each comes with foldout pages illustrating an old collection that foreshadowed certain ideas that are central to said show . At the end of the books you’ll find even more quotes arranged around broader topics such as “creativity”, “color” and “business”. There’s also a timeline and a list of all of the collection titles starting from around 1981. The book finishes with a larger print of the photograph included in the back cover.

Although the book is a very light read its thesis serves to explain how is that Rei's managed to continually shake up fashion's status quo all the while finding new forms of beauty.

This review is also very useful: https://www.sz-mag.com/news/2017/05/book-review-rei-kawakubocomme-des-garcons-art/

Last edited by a moderator:

Not Plain Jane

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Mar 3, 2010

- Messages

- 15,479

- Reaction score

- 844

thank you so much yohji_addict, both for your own review and the additional link. very warmly appreciated!

YohjiAddict

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- May 26, 2016

- Messages

- 3,660

- Reaction score

- 5,216

I'm sharing excerpts from the exhibition's catalogue: Andrew Bolton's introductory essay, the conversation between him and Rei and a list that has the names of each and every womenswear show up until that point.

P.S: I know the quality is not the best but this book is coffee table sized so it's quite hard to manouver and did not fit in my scanner...sorry.

P.S: I know the quality is not the best but this book is coffee table sized so it's quite hard to manouver and did not fit in my scanner...sorry.

Similar Threads

- Replies

- 329

- Views

- 69K

- Replies

- 12

- Views

- 5K

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)