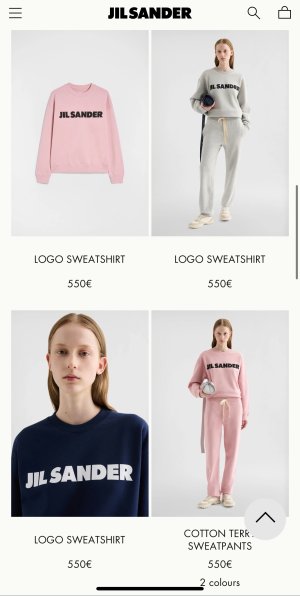

Keep in mind that Jil Sander is mainly renembered for her heydays in the 1990ies, bringing an austere modernity (people would describe it as 'nordic', although perhaps a lot of scandinavian and german people identify with this style) where there was before only Armani - And let me say perhaps as someone coming from an area not very far from where Jil Sander grew up, I feel that it speaks of our culture, distinctly different from the French and the Italians.

German culture has that distinctly spare and unadorned feel when you think of Bauhaus design, Dieter Rahms and perhaps also the fact that German women are not very much known for a voluptuous feminity - Barely wearing make up, form-fitting clothes that accentuate womanly curves, heels, etc. - The frivolous attributes most fashion-following women enjoy to play with.

So yes, practicality, the saying 'form follows function', they are probably coming from that protestant-minded culture. It‘s the reason why there has been since their arrival on the fashion scene a strong following for Yohji and the Flemish (Belgian) designers.

I think the cultural and social mindset of a country or region can certainly inform a designer's aesthetic to some extent, but it doesn’t determine it. Fashion is, after all, a form of applied art, it shouldn’t be strictly confined to a fixed cultural value system.

Jil Sander’s work clearly reflects certain characteristics often associated with modern German/Nordic sensibilities – discipline, austerity, clarity, and pragmatism. But that doesn’t mean she’s obliged to represent a broader aesthetic tradition of that region. Because she was such a prominent figure, it’s easy to assume that other designers from the same cultural background must share similar visual languages. Yet that assumption often reduces individual creativity to cultural determinism – for example, linking everything back to Bauhaus or the "cold clarity" of German design.

On the flip side, countries like China, Vietnam, or the former Soviet bloc – all of which were shaped ideologically by Marxism-Leninism (a very avant-garde philosophy if you ask me) at the core – didn’t necessarily gravitate toward Constructivism or Brutalism in aesthetics. In fact, there’s often a fascination with classical European opulence instead. That contradiction shows just how slippery the connection between ideology, culture, and aesthetic taste can be.

Similarly, I’ve never felt that Giorgio Armani’s works embodies "Italian-ness" in any overt sense. If anything, I often see more influence from non-European cultures and from the works of people like Tadao Ando, Pierre Chareau or Eileen Gray than from any lineage rooted in couture history.

Regarding Belgian designers – their relationship with avant-garde feels highly fragmented to me. Many of them seem more invested in exploring radicalism – whether through anti-fashion gestures, deliberate distortion, or subversion of form – rather than developing avant-garde as a coherent language rooted in movement, silhouette, or philosophical abstraction, as seen in the work of Japanese designers like Rei Kawakubo or Issey Miyake. This makes the Belgians hard to group together stylistically, even if they’re often appreciated by those who seek out "unconventional fashion". Oh and within Japan itself, we have someone like Kansai Yamamoto, whose aesthetic is on the complete opposite end of the spectrum from Yohji Yamamoto.

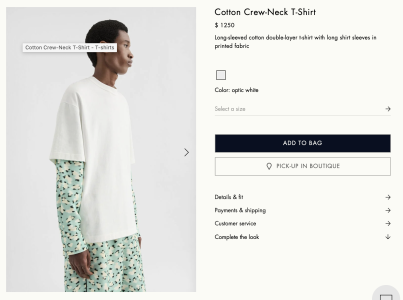

What I find somewhat frustrating is the recurring idea that one’s worldview or aesthetic philosophy inevitably shapes how one dresses – as if your clothing must align with your intellectual position. In reality, that rarely holds. You can be a Marxist or an avant-garde composer/film maker and still wear Dolce & Gabbana, Chanel or Loro Piana – simply because you like how it looks or feels. Sometimes people just want to elevate their appearance without overthinking it or attaching symbolic weight to every choice. And sometimes, attributing meaning to fashion becomes a way of retroactively justifying choices that are, at heart, instinctive or taste-based.