Why Yves Saint Laurent was never happy

As Pierre Bergé, partner of the great designer, prepares to auction their art collection, he reveals YSL's struggle with depression

By Celia Walden

Last Updated: 9:14PM GMT 29 Jan 2009

Partners for 50 years: the late Yves Saint Laurent with Pierre Berge Photo: John Van Hasselt/CORBIS SYGMA

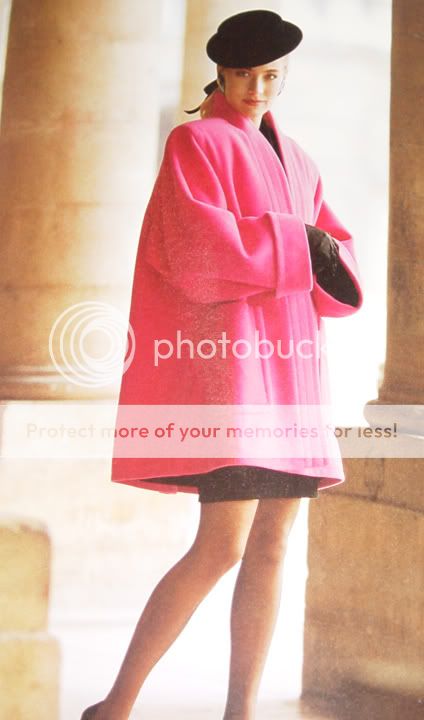

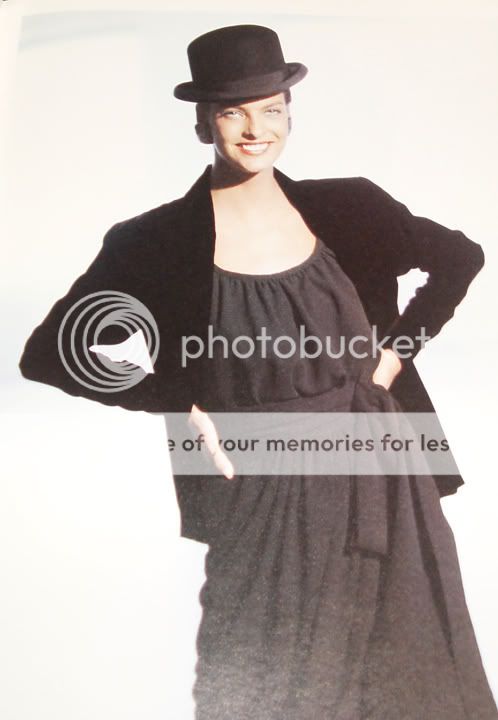

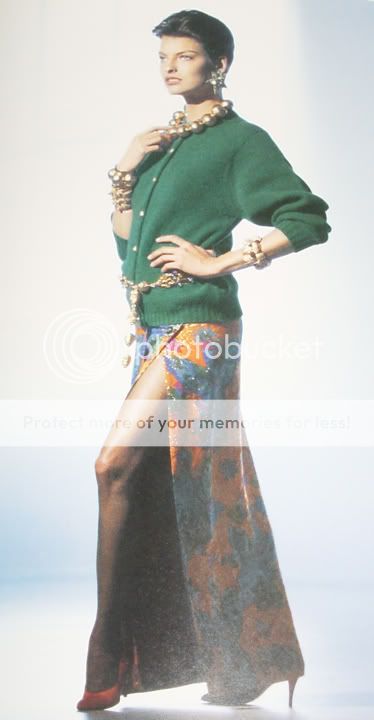

There are few female pleasures more finely distilled than slipping on a jacket or dress made by a truly great designer. As one of the most revered stylists of the 20th century, the late Yves Saint Laurent dispersed that joy liberally and will continue to do so, through his designs, despite his death in June last year. Now, the man who spent half a century as his lover and business partner has revealed the cost of that creativity on the designer’s mental health.

“Designing made him deeply miserable,” says Pierre Bergé, who co-founded the YSL couture house with Saint Laurent in 1961. “Sadly, Yves was not built for joy. He was an unhappy person who didn’t have a taste for life. Occasionally, he was happy, but life was difficult for him. The depression ran deep.”

We are in Bergé’s office on the first floor of the Fondation Saint Laurent on Avenue Marceau to discuss his decision to sell off the art collection the couple spent 50 years amassing. In what is being called “the sale of the century”, 730 pieces – including Old Master drawings, Renaissance bronzes and works by Ingres, Géricault, Frans Hals, Picasso, Matisse, Braque, Léger and Mondrian – from Saint Laurent’s apartment will go under the hammer at Christie’s next month. They are expected to fetch about £240 million.

Bergé, a sprightly 79-year-old, shakes his head serenely when I ask whether selling the collection was a hard decision to make.

“Not at all. The second I knew that Yves was ill, condemned, I knew I would sell everything,” he says, referring to the brain cancer that eventually killed his partner. “I think that the day after the sale,” he pauses, “I will feel liberated.”

Behind Bergé – a neat, impatient figure in pin-stripes – hangs an enormous Warhol portrait of his late lover. “I did think about using the collection to create a museum,” asserts Bergé, his voice veering from stern to whimsical, “but it would have been too expensive and I am happy with my decision.”

Throughout their fractious relationship, Bergé was often assigned the role of decision-maker. The son of a tax official and a Montessori teacher from Bordeaux, he is described by writer Alicia Drake as being “fascinated by the idea of the artiste, the creator and the creative spirit”. Small wonder, then, that when he first met 22-year-old Saint Laurent, then working as the head designer at Dior, Bergé instantly fell in love with him.

He was, he recalls, “a strange, shy boy. He wore very tight jackets as if he was trying to keep himself buttoned up against the world – he reminded me of a clergyman, very serious, very nervous.” Six years older, with an established reputation in le grand monde, Bergé had his own potent appeal. “Everything I didn’t have, he had,” Saint Laurent later said. “His strength meant I could rest on him when I was out of breath.”

Conscripted in 1960 to fight in the Algerian war, where he was brutalised, the delicate Saint Laurent was committed to a mental hospital for electric shock treatment and psychoactive drugs, something both Bergé and Saint Laurent blame for his later drug dependency.

Only an appreciation of art provided any respite. “We never disagreed on what we liked,” says Bergé, “and because it is all of such exceptional quality, it all goes well together, despite being very different in style.” The collection seems to epitomise Saint Laurent’s lifelong yearning for joy.Legend has it that the flat on rue de Babylone was so packed full of treasures that there were Monets hanging in the lavatories. True? Bergé shrugs. “Well, yes.”

He and Saint Laurent began collecting in the 1970s, following the launch of Opium (which became the world’s best-selling perfume, making them millions). The collection seems to have provided the glue in a relationship which periodically became unstuck. “In the end it all comes down to the need you have for each other. Yves and I never split up,” he insists, despite reports to the contrary. “We lived separately but we never split up.”

Bergé is unemotional about the couple’s decision to become civil partners shortly before Saint Laurent was incapacitated by brain cancer. “We did it not for romantic reasons but because we had lived 50 years together: it was about achievement, and I had fought for it to be possible, so that homosexuals would be allowed to leave things to their partners.”

Bergé is thankful that, at the end, Saint Laurent was not aware of his own deterioration. “He didn’t understand the nature of his illness. He wouldn’t have had the psychological courage to cope with it.”

He is adamant that both he and Saint Laurent were of the belief that “fashion is not an art form”, although, he concedes, it “may take an artist to create fashion”. Does that not denigrate Saint Laurent’s very genius? “Not at all,” he argues. “Saint Laurent detested fashion.” I wait for the punch line. “Style is what he liked.”

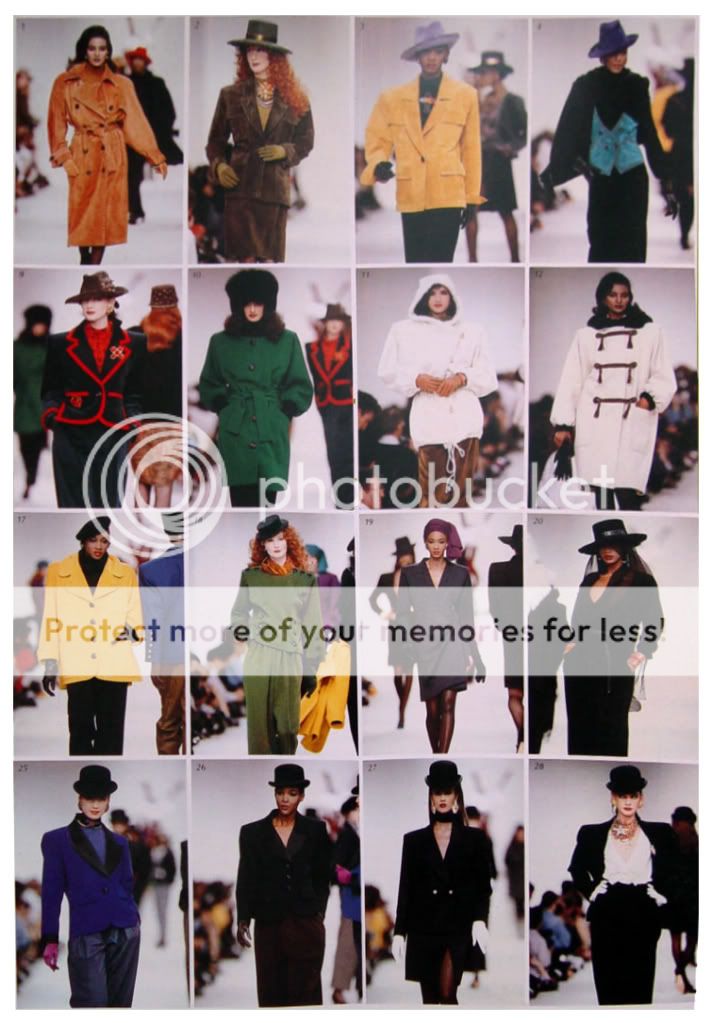

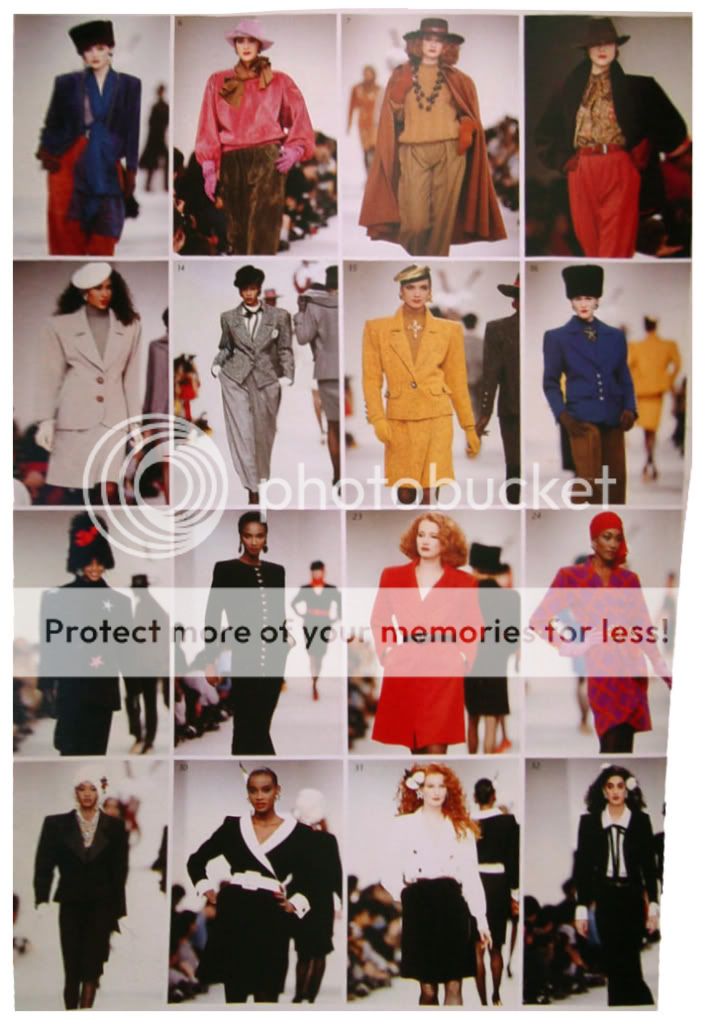

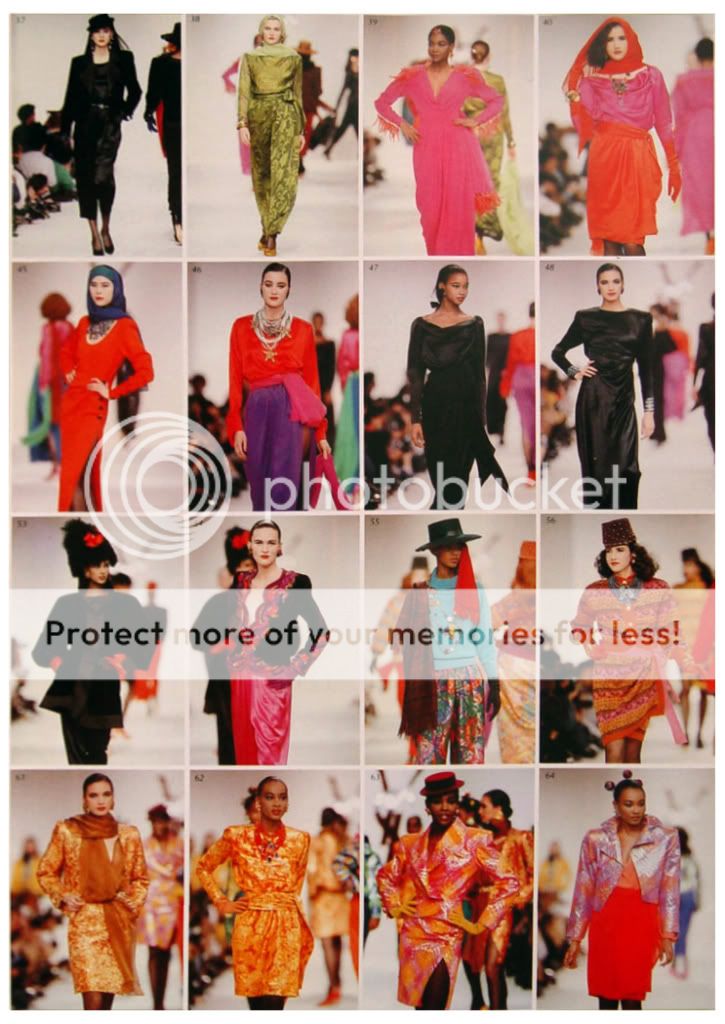

Would the two of them, for example, dissect a woman’s outfit when she walked in the room? “Absolutely not,” he maintains, pained at my vulgarity. “We believed that fashion was to be worn, not to be made into a catwalk show, into theatre. It exists to dress women. Chanel may have given women liberty but Saint Laurent gave them power. By putting women in smoking jackets, he gave them the same confidence and possibility to affirm themselves as men. I see Saint Laurent’s influence today everywhere – everywhere.”

The state of fashion today provokes wonderfully disparaging remarks from Bergé. “These luxury brands are all sadly being bought by nouveaux riches now: Russians or Arabs. There is a real monetary insolence out there at the moment.” And what of the Italian high- fashion brands, I goad him, remembering Bergé’s incendiary assertion that “Italians don’t make clothes, they make spaghetti”. “Versace is nothing and now that he’s dead, it’s less than nothing. And Cavalli’s no good either.”

Models such as Kate Moss, Victoria Beckham and Heidi Klum, who have created their own ranges, are worthy of yet more derision. “I think it’s ridiculous. It’s not because you were a model that you have any talent. Being a designer is a big job, a great job, and one you have to work very, very hard for. Which is why those 'model’ ranges don’t generally work and tend to die out pretty quickly.”

He seems to have tempered his earlier opinion of current Yves Saint Laurent designer, Stefano Pilati, about whom he was at first dubious. “He’s in a difficult situation because if he copies Saint Laurent people will say he’s talentless, and if he does personal things people will say he is not faithful to the brand. But he seems to be doing OK.”

Bergé refers to his lover as Yves when we discuss his personality, and Saint Laurent, (even, on occasion, Monsieur Saint Laurent) when we discuss his achievements. This tells you all you need to know about the nature of their relationship, where the pride and respect are so strong that banal, sentimental love seems belittled in comparison.

“Next year, I plan to throw a huge retrospective in his memory at the Petit Palais,” he says, shifting a little on his chair to show that the interview should be wrapping up now.

In what ways does he miss Saint Laurent, eight months on? “In the little ways,” he says. “Like the other day, I went to the opera and it was so beautiful – and I missed him then because I couldn’t share that with him.”

The Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé Collection is to be sold by Christie’s in association with Pierre Bergé & Associates Auctioneers on February 23-25 at the Grand Palais, Paris (christies.com)

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/fashion/4389152/Why-Yves-Saint-Laurent-was-never-happy.html

)

)